//features//

Fall 2017

A "Dose of Sun" with The Met's David Hockney:

an Interview with Curator Ian Alteveer

Julia Crain

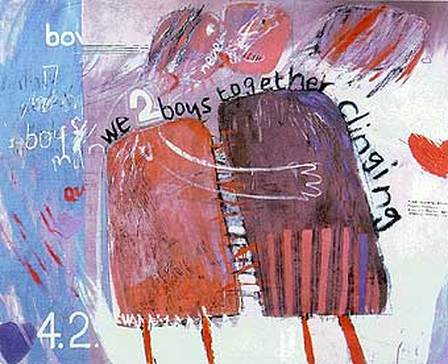

The virulence of today’s political climate has left many wondering: How can we draw people of different beliefs, backgrounds, and identities together? Art often provides us with answers. Artists afford viewers an opportunity to exercise empathy for others, as they often shed light on various social realities, making them palpable for viewers. British artist, David Hockney (born in 1937), exemplifies this quality, as his work renders visible queer desire in a way that captures the beauty of such intimacy, longing, and connection. He does so while working against a sociopolitical backdrop of oppression and discrimination—not unlike the culture wars taking place in today’s America.

The Current spoke with Ian Alteveer, Curator of Modern & Contemporary Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, about organizing David Hockney, a retrospective exhibition of Hockney’s work on view at The Met through February 25, 2018. The exhibit celebrates Hockney’s nearly 60-year-long career. As a whole, Hockney’s oeuvre reflects his experimental approach to abstraction and demonstrates a rigorous exploration of the History of Painting.

Mr. Alteveer earned his BA from Stanford University and completed his qualifying exams for a PhD in Art History at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. His repertoire of exhibitions at The Met includes the retrospectives Kerry James Marshall: Mastry (2016) and Marisa Merz: The Sky Is a Great Space (2017). This interview has been edited and condensed.

Julia Crain: What inspired you to become a curator?

Ian Alteveer: I realized late in the game—during my sophomore year in college—that I was interested in Art History. At that point, I had already become a Comparative Literature major, working on French and Italian Modernism, but I began to think seriously about what it would mean to work in a museum. I spent a summer documenting the 18th Century painting collection of a regional museum in France, and I applied the following year for an internship at the National Gallery in Washington. At the National Gallery of Art, I worked for Philip Conisbee, who was their curator of French painting, and I loved the atmosphere of working at a museum. When I graduated, I tried very hard to get a museum job in San Francisco, but no one would call me back. I then had to take a roundabout route. I worked briefly for an auction house in San Francisco, and then I landed at galleries. I really enjoyed my role at a contemporary art gallery, working with living artists and helping to install their shows, sell their work, and talk to collectors and curators about their practice. I then came to New York to study at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, always with the idea that I wanted to be a curator. I knew that, in order to work at a place like The Met, I would need graduate work and research experience in Art History. That’s how it began.

JC: As a curator of Contemporary Art, you typically work with living artists. What attracts you most to working with living artists, and what are some of the potential drawbacks of doing so?

IA: The first living artist I worked with was Bruce Conner, and that was in my early days at the gallery in San Francisco. Conner was an incredible artist and was so involved with the Beat Generation in San Francisco, and I was terrified [to work with him]. He was very particular. I had known, from the gallery owner, that I was to keep [Conner’s] work—that was on consignment to the gallery—in perfect condition because he was known to come into the back room and threaten to pull his work out of the gallery altogether if it was at all dusty or badly put away. In the end, however, he was wonderful, and we got along well. I loved being able to talk with him about the work he had brought to show and hear old stories about past decades in San Francisco. There was something magical about that experience. Every artist is different. Some are kinder or more interesting than others when you meet them in person, but each has a unique story to tell.

JC: It sounds like you’re drawn to the dynamism of hearing artists’ ideas directly from them.

IA: You know, Art History often tells us, at least in recent years, that the voice of the artist is the least important part of the objects that they have made, but I think that there is a middle road. I try to approach Art History [by examining] the artist’s experience and the context in which they made a work, [as opposed to] the French Structuralist idea of the “Death of the Author.” Part of this kind of approach is hearing [their experiences] from them.

JC: What are your markers of success for a show you curate?

IA: That’s hard. One of them, if the artist is alive, is making sure the artist is happy. But you always want to make sure, too, that it’s not just about the artist because, after all, the show is meant for the public to see and learn from. If we’re talking about a monographic show (an exhibition of one artist), a really successful show is one that presents, as clearly as it can, the highs of an artist’s career. Sometimes you can do that with text, with an audio guide, or with a guided tour. [Museum visitors], of course, haven’t had the three or four years of work, research, and reading you have done on this person’s work. The question, then, is: How do you telegraph all of that information in a clear and interesting way?

JC: How were you first introduced to David Hockney’s work, and how did you decide on creating this show?

IA: I’m sure it was as a child. He’s someone you read about in encyclopedia books on the History of Art, so in that sense, he’s a pretty famous name. We also often associate him so much with California, and I love California. Hockney was born in England, went to graduate school in London, and then came to California. I discovered, too, his interest in representing queer desire, starting from a very early stage in his career. My interest in studying his work just developed from there.

JC: It’s both that he is a major figure in contemporary histories of art, and also that you have a personal connection to his work.

IA: Yes, it’s striking to see. One of the exciting things for me is that this is the first retrospective for Hockney in New York in 30 years, so it’s an opportunity to show a new generation of museumgoers his full career. One of the takeaways [from the show] is how radical some of the subjects in his early paintings are. [He made those] at a very young age, in his twenties—a time before the decriminalization of homosexuality in the UK (which doesn’t happen until 1967)—so he’s really fearless in a way. He is presenting these stories on the surfaces of his paintings in a time when [homosexuality is] literally illegal.

JC: What do you think it means to view these works in today’s political context?

IA: I think, in a way, there are answers here for some of us who are frustrated by the current political climate. Artists often show us the way around really difficult moments by translating the world into something that we can digest. They [often] push boundaries in a beautiful way and in a way that can capture people’s attention, even when they disagree with what’s being depicted in a given work. Someone, for example, who is adamantly opposed to relationships between two men or two women might have the sneaking sensation in seeing some of Hockney’s work that actually, there is nothing wrong with [same-sex relationships]. There are ways in which art can sneak under our skin. The artist Felix Gonzalez Torres called it “being a spy.” He was working in the ‘90s, at the height of the AIDS crisis—when the government was completely ignoring it. When faced with that kind of atmosphere, to “be a spy” and to be able to get under people’s skin, [so that they] realize that participating in something that might be queer can also be delicious, is a really powerful possibility. I have a lot of faith in art’s ability to teach us other lessons.

JC: What would you identify as Hockney’s most significant artistic contributions?

IA: In a basic sense, he’s known for painting Los Angeles in the 1960s, with these kind of wonderfully planar, flat compositions of the ubiquitous backyard swimming pools and the boxy Modernist houses and office buildings. In a way, his work stands in for our idea of L.A. at a certain time. His early paintings are redolent of a time in London (at the end of the ‘50s and the beginning of the ‘60s), when the city is beginning to wake up after a brutal postwar decade, when it’s gloomy and dark, the economy is bad, and people are so repressed … the burgeoning of Hockney’s discovery of his sexuality comes through in those pictures. Wherever he is in his career, his works speak to what’s going on in the larger world, even when his subject matter is so personal. There’s also always something to be said for what’s happening in the larger world of art. He’s learning how to be a painter at a time when artists are supposed to be making abstract paintings—in the early ‘60s—but he feels the need to inject his own stories and the things he cares about into the pictures. … It’s quite radical at the time. You have these wonderful amalgams of abstraction and figuration. He continued to ape styles of abstraction, such as Color Field painting (popular among artists including Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Lewis, Kenneth Noland, and Frank Stella). He does so again in the ‘80s, by using Picasso [as a model] to explore things like reverse perspective.

JC: What were some of the biggest challenges in curating this show?

IA: I really benefited from my collaboration on this exhibition with curators at the Tate Britain in London and at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, but that kind of international collaboration can also be difficult. How do we coordinate our meetings, and how do we get on the same page about the checklist, and how do we all go visit the artist when they live 8,000 miles away from him? Another aspect, of some concern, was that we each had different sized galleries for the exhibition, even though we all wanted a seamless tour. It makes it a lot easier, from a budgetary standpoint, if you have the same pictures in each venue. Paris was the largest venue: it had double the square footage that I have here in New York, so [curators] there had to add a significant amount [of works]. However, that makes for an interesting tour. … It is exciting to see how the show has different lives across venues. There’s still the core paintings that traveled along the way, and then there are some changes.

JC: How does this show fit into the aims of your curatorial practice as a whole? How does it fit into The Met’s vision for Modern & Contemporary Art?

IA: For me, I mentioned my love of art from California. [This show] fits in with that trajectory in my practice, as I’ve worked on a number of projects that have dealt with California. I also, of course, love working with living artists, and here’s another great artist I could spend time with and learn more about myself. In terms of the Modern & Contemporary Department and the Museum more generally, one of our program’s deep interests, both here and at The Met Breuer, is to present artists and groups of artists who work against a passage of history. Artists who, yes, are of their moment, but who also are always looking back at art of the past. Hockney, with his interest in figures like Picasso, Van Gogh, and Piero della Francesca, has resonances with art all around The Met’s building.

JC: What do you hope people take away from this show?

IA: A lot of things. One of them, which [my colleagues and I] were just joking about, is that as we’re plunging into the darkness and the coldness of winter in New York, it’s fun to be in those galleries with their wonderfully bright, shining colors. You feel a dose of sun, and you also [get the chance to] commune with this amazing artist and his group of friends. One of my favorite spaces in the show is the central gallery with double portraits (from 1968 to 1977). Surrounded by those works, you feel like you are visiting the living rooms and the homes of some of Hockney’s nearest and dearest, and they’re holding court for you. You pass into what it’s like to be a part of their world. More broadly, to see how Hockney is completely unafraid to be fluid with his style and to incorporate other styles of painting into his practice, is really exciting.

JC: Lastly, what is your favorite painting in the show?

IA: My favorite of his “Road Trip” paintings is called Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians (1965). That is a painting Hockney made in Boulder, Colorado, where he was teaching during the summer of 1965. Boulder is an amazing place: it’s got this incredible view of the Rocky Mountains, but Hockney’s studio, he says, had no windows. So he’s painting an imaginary scene of the mountains with figures standing in front of them. In that painting, he’s quoting different modes of abstract painting, so it’s a landscape painted with silver paint, like the way that Frank Stella had painted his Aluminum Paintings a few years before. It also has bands of color that are like a Kenneth Noland abstraction. So it’s a painting that speaks about American landscape, but it also speaks about American abstract painting—all in the same picture. [Another favorite of mine is] the fabulous Pool and Steps, Le Nid du Duc (1971). He stained the lower half of the canvas, the pool water, using Helen Frankenthaler’s technique, whereas the upper half of the painting is a meticulously painted acrylic zone of realist, bright, Mediterranean sun.

The Current spoke with Ian Alteveer, Curator of Modern & Contemporary Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, about organizing David Hockney, a retrospective exhibition of Hockney’s work on view at The Met through February 25, 2018. The exhibit celebrates Hockney’s nearly 60-year-long career. As a whole, Hockney’s oeuvre reflects his experimental approach to abstraction and demonstrates a rigorous exploration of the History of Painting.

Mr. Alteveer earned his BA from Stanford University and completed his qualifying exams for a PhD in Art History at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. His repertoire of exhibitions at The Met includes the retrospectives Kerry James Marshall: Mastry (2016) and Marisa Merz: The Sky Is a Great Space (2017). This interview has been edited and condensed.

Julia Crain: What inspired you to become a curator?

Ian Alteveer: I realized late in the game—during my sophomore year in college—that I was interested in Art History. At that point, I had already become a Comparative Literature major, working on French and Italian Modernism, but I began to think seriously about what it would mean to work in a museum. I spent a summer documenting the 18th Century painting collection of a regional museum in France, and I applied the following year for an internship at the National Gallery in Washington. At the National Gallery of Art, I worked for Philip Conisbee, who was their curator of French painting, and I loved the atmosphere of working at a museum. When I graduated, I tried very hard to get a museum job in San Francisco, but no one would call me back. I then had to take a roundabout route. I worked briefly for an auction house in San Francisco, and then I landed at galleries. I really enjoyed my role at a contemporary art gallery, working with living artists and helping to install their shows, sell their work, and talk to collectors and curators about their practice. I then came to New York to study at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, always with the idea that I wanted to be a curator. I knew that, in order to work at a place like The Met, I would need graduate work and research experience in Art History. That’s how it began.

JC: As a curator of Contemporary Art, you typically work with living artists. What attracts you most to working with living artists, and what are some of the potential drawbacks of doing so?

IA: The first living artist I worked with was Bruce Conner, and that was in my early days at the gallery in San Francisco. Conner was an incredible artist and was so involved with the Beat Generation in San Francisco, and I was terrified [to work with him]. He was very particular. I had known, from the gallery owner, that I was to keep [Conner’s] work—that was on consignment to the gallery—in perfect condition because he was known to come into the back room and threaten to pull his work out of the gallery altogether if it was at all dusty or badly put away. In the end, however, he was wonderful, and we got along well. I loved being able to talk with him about the work he had brought to show and hear old stories about past decades in San Francisco. There was something magical about that experience. Every artist is different. Some are kinder or more interesting than others when you meet them in person, but each has a unique story to tell.

JC: It sounds like you’re drawn to the dynamism of hearing artists’ ideas directly from them.

IA: You know, Art History often tells us, at least in recent years, that the voice of the artist is the least important part of the objects that they have made, but I think that there is a middle road. I try to approach Art History [by examining] the artist’s experience and the context in which they made a work, [as opposed to] the French Structuralist idea of the “Death of the Author.” Part of this kind of approach is hearing [their experiences] from them.

JC: What are your markers of success for a show you curate?

IA: That’s hard. One of them, if the artist is alive, is making sure the artist is happy. But you always want to make sure, too, that it’s not just about the artist because, after all, the show is meant for the public to see and learn from. If we’re talking about a monographic show (an exhibition of one artist), a really successful show is one that presents, as clearly as it can, the highs of an artist’s career. Sometimes you can do that with text, with an audio guide, or with a guided tour. [Museum visitors], of course, haven’t had the three or four years of work, research, and reading you have done on this person’s work. The question, then, is: How do you telegraph all of that information in a clear and interesting way?

JC: How were you first introduced to David Hockney’s work, and how did you decide on creating this show?

IA: I’m sure it was as a child. He’s someone you read about in encyclopedia books on the History of Art, so in that sense, he’s a pretty famous name. We also often associate him so much with California, and I love California. Hockney was born in England, went to graduate school in London, and then came to California. I discovered, too, his interest in representing queer desire, starting from a very early stage in his career. My interest in studying his work just developed from there.

JC: It’s both that he is a major figure in contemporary histories of art, and also that you have a personal connection to his work.

IA: Yes, it’s striking to see. One of the exciting things for me is that this is the first retrospective for Hockney in New York in 30 years, so it’s an opportunity to show a new generation of museumgoers his full career. One of the takeaways [from the show] is how radical some of the subjects in his early paintings are. [He made those] at a very young age, in his twenties—a time before the decriminalization of homosexuality in the UK (which doesn’t happen until 1967)—so he’s really fearless in a way. He is presenting these stories on the surfaces of his paintings in a time when [homosexuality is] literally illegal.

JC: What do you think it means to view these works in today’s political context?

IA: I think, in a way, there are answers here for some of us who are frustrated by the current political climate. Artists often show us the way around really difficult moments by translating the world into something that we can digest. They [often] push boundaries in a beautiful way and in a way that can capture people’s attention, even when they disagree with what’s being depicted in a given work. Someone, for example, who is adamantly opposed to relationships between two men or two women might have the sneaking sensation in seeing some of Hockney’s work that actually, there is nothing wrong with [same-sex relationships]. There are ways in which art can sneak under our skin. The artist Felix Gonzalez Torres called it “being a spy.” He was working in the ‘90s, at the height of the AIDS crisis—when the government was completely ignoring it. When faced with that kind of atmosphere, to “be a spy” and to be able to get under people’s skin, [so that they] realize that participating in something that might be queer can also be delicious, is a really powerful possibility. I have a lot of faith in art’s ability to teach us other lessons.

JC: What would you identify as Hockney’s most significant artistic contributions?

IA: In a basic sense, he’s known for painting Los Angeles in the 1960s, with these kind of wonderfully planar, flat compositions of the ubiquitous backyard swimming pools and the boxy Modernist houses and office buildings. In a way, his work stands in for our idea of L.A. at a certain time. His early paintings are redolent of a time in London (at the end of the ‘50s and the beginning of the ‘60s), when the city is beginning to wake up after a brutal postwar decade, when it’s gloomy and dark, the economy is bad, and people are so repressed … the burgeoning of Hockney’s discovery of his sexuality comes through in those pictures. Wherever he is in his career, his works speak to what’s going on in the larger world, even when his subject matter is so personal. There’s also always something to be said for what’s happening in the larger world of art. He’s learning how to be a painter at a time when artists are supposed to be making abstract paintings—in the early ‘60s—but he feels the need to inject his own stories and the things he cares about into the pictures. … It’s quite radical at the time. You have these wonderful amalgams of abstraction and figuration. He continued to ape styles of abstraction, such as Color Field painting (popular among artists including Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Lewis, Kenneth Noland, and Frank Stella). He does so again in the ‘80s, by using Picasso [as a model] to explore things like reverse perspective.

JC: What were some of the biggest challenges in curating this show?

IA: I really benefited from my collaboration on this exhibition with curators at the Tate Britain in London and at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, but that kind of international collaboration can also be difficult. How do we coordinate our meetings, and how do we get on the same page about the checklist, and how do we all go visit the artist when they live 8,000 miles away from him? Another aspect, of some concern, was that we each had different sized galleries for the exhibition, even though we all wanted a seamless tour. It makes it a lot easier, from a budgetary standpoint, if you have the same pictures in each venue. Paris was the largest venue: it had double the square footage that I have here in New York, so [curators] there had to add a significant amount [of works]. However, that makes for an interesting tour. … It is exciting to see how the show has different lives across venues. There’s still the core paintings that traveled along the way, and then there are some changes.

JC: How does this show fit into the aims of your curatorial practice as a whole? How does it fit into The Met’s vision for Modern & Contemporary Art?

IA: For me, I mentioned my love of art from California. [This show] fits in with that trajectory in my practice, as I’ve worked on a number of projects that have dealt with California. I also, of course, love working with living artists, and here’s another great artist I could spend time with and learn more about myself. In terms of the Modern & Contemporary Department and the Museum more generally, one of our program’s deep interests, both here and at The Met Breuer, is to present artists and groups of artists who work against a passage of history. Artists who, yes, are of their moment, but who also are always looking back at art of the past. Hockney, with his interest in figures like Picasso, Van Gogh, and Piero della Francesca, has resonances with art all around The Met’s building.

JC: What do you hope people take away from this show?

IA: A lot of things. One of them, which [my colleagues and I] were just joking about, is that as we’re plunging into the darkness and the coldness of winter in New York, it’s fun to be in those galleries with their wonderfully bright, shining colors. You feel a dose of sun, and you also [get the chance to] commune with this amazing artist and his group of friends. One of my favorite spaces in the show is the central gallery with double portraits (from 1968 to 1977). Surrounded by those works, you feel like you are visiting the living rooms and the homes of some of Hockney’s nearest and dearest, and they’re holding court for you. You pass into what it’s like to be a part of their world. More broadly, to see how Hockney is completely unafraid to be fluid with his style and to incorporate other styles of painting into his practice, is really exciting.

JC: Lastly, what is your favorite painting in the show?

IA: My favorite of his “Road Trip” paintings is called Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians (1965). That is a painting Hockney made in Boulder, Colorado, where he was teaching during the summer of 1965. Boulder is an amazing place: it’s got this incredible view of the Rocky Mountains, but Hockney’s studio, he says, had no windows. So he’s painting an imaginary scene of the mountains with figures standing in front of them. In that painting, he’s quoting different modes of abstract painting, so it’s a landscape painted with silver paint, like the way that Frank Stella had painted his Aluminum Paintings a few years before. It also has bands of color that are like a Kenneth Noland abstraction. So it’s a painting that speaks about American landscape, but it also speaks about American abstract painting—all in the same picture. [Another favorite of mine is] the fabulous Pool and Steps, Le Nid du Duc (1971). He stained the lower half of the canvas, the pool water, using Helen Frankenthaler’s technique, whereas the upper half of the painting is a meticulously painted acrylic zone of realist, bright, Mediterranean sun.

//Julia Crain is a senior in Barnard College and is Literary & Arts Editor of The Current. She can be reached at [email protected].