//features//

Spring 2020

Spring 2020

A Jewish Nurse in Ramadan TV Show Can Only Heal So Much

Maya Bickel

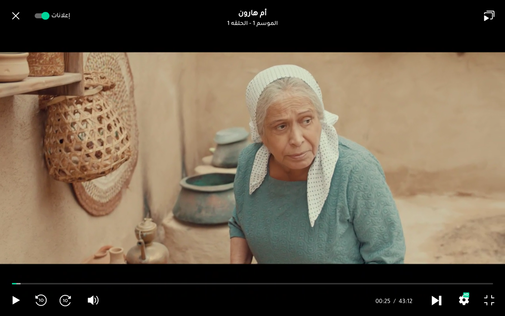

Umm Haroun, a small, elderly Jewish woman, appears on the screen in a light turquoise dress and a white headscarf. As she walks across the enclosed courtyard, she begins to explain the premise of the TV show in a voiceover. “In the past, love mattered...it brought together families and brothers, and didn’t separate us into sects or disperse us based on religion.” But there were conflicts that were hidden, and these conflicts, Umm Haroun warns, “if they persist, will fuel the fire of hatred, jealousy, and killing.”

The Saudi-produced TV show “Umm Haroun” (literally “mother of Aaron,” named after its main character) follows a Jewish nurse in an unnamed Gulf country in the 1940s and the relationships that unfold between her family and their Christian and Muslim neighbors. Even before this new TV show aired in April 2020, it was the subject of heated debates across the Arab world that offers a view into the complicated opinions held about Jews and Israel. Although the show’s controversy centers on Jews who were forced out of Arab lands following the creation of the State of Israel, those Jews are left out of the conversation.

The show’s critics consider these Jews, many of whom are now Israeli citizens, stand-ins for the State of Israel. Any sympathetic portrayal of them on TV is equivalent to a sympathetic portrayal of Israel. Even more concerning to the critics is the show’s portrayal of Jews as victims of discrimination and, early on in the show, extreme violence: a Jewish man is murdered soon after the village finds out about the creation of the State of Israel. The victimization of the Jewish characters is seen as a betrayal of the Palestinian cause and a blatant attempt to normalize relations with Israel.

The show’s supporters, on the other hand, praise it for addressing a long overlooked part of Arab history, that of thriving Jewish communities throughout the Middle East and North Africa. “Umm Haroun” paints the Jewish characters as Arab—just as Arab as their Muslim and Christian counterparts, even though they wear Star of David necklaces and prayer shawls. Hayat al-Fahad, the Kuwaiti actress who plays Umm Haroun, said in an interview with Kuwaiti newspaper Al-Anba that she chose to act in this show “because it deals with a group of people who were and still are in our world.” “It is true that we are no longer with them, but we must reach them through this older time period because we have a generation of youth who have no information on them,” she added.

Despite the show’s sympathetic portrayal of Arab Jews, it does not seem to have consulted Arab Jews, or any Jews, very carefully. Hebrew sentences are full of mistakes and Hebrew is depicted as being written from left to right. The show also portrays the Jewish community as large when in fact Jewish communities in the Gulf were relatively small. The show’s inability to communicate directly with the community it tries to portray further highlights the societal rifts that have emerged since these Jews’ expulsion.

Since the show was not entirely successful at integrating the actual voices of Arab Jews, it is unsurprising that attempts by the media to include Jewish voices were also unsuccessful. An Arabic Al Jazeera article titled “The Demise of Israel and the Legitimization of Normalization: How Did Israeli Media Read the Ramadan TV Dramas?” attempts to bring Israeli perspectives on the controversy into the media conversation. The attempt reveals a curiosity among some corners of Arabic language media over how Israel and its citizens, some of whom are Arab Jews, are thinking about the controversy. But the article that results is far from an accurate reflection of Israeli opinions on the show.

The Al Jazeera article argues that, all in all, Israeli media looks favorably upon the TV show, quoting the Arab affairs commentator of KAN, an Israeli state-owned TV channel, and Yaron Friedman, Arab affairs commentator of Yediot Aharonot, one of Israel’s two leading dailies. According to Al Jazeera, this favorable outlook stems from their perception of “Umm Haroun” as a sign of changes in the Arab world that are bringing certain countries closer to Israel. However, Al Jazeera misreads Friedman’s article, in ways both deliberate and inadvertent, and only includes quotes that support this understanding of the politics-focused Israeli reception.

According to the Al Jazeera article, “Dr. Yaron Friedman, Arab affairs commentator for the newspaper Yediot Aharonot thinks that the show Umm Haroun sends a political message that ‘Gulf countries are paving the way towards normalization with Israel.’” Al Jazeera, perhaps inadvertently, left out the crucial beginning of Friedman's sentence. In the original Hebrew article Friedman writes, “according to its critics, the show Umm Haroun....” (emphasis added). Friedman’s article quotes opinions found in Arab media about the show. Al Jazeera, though, uses his quote as an example of an opinion found in Israeli media.

This opinion is in fact expressed in other parts of Friedman’s article, but the use of the misquote suggests that Friedman’s article was quickly scoured for quotes that fit a certain narrative of Israeli responses. Since Al Jazeera’s article focuses on Israel’s positive reception of “Umm Haroun” and its embrace of the show’s geopolitical significance, it is no surprise that Al Jazeera also deliberately chose not to include one of Friedman’s main points.

His article is titled “The Jews are also victims: The Israeli Storm in the Ramadan Shows,” and analyzes the controversy over “Umm Haroun” for its geopolitical significance and also for its significance for Arab Jews. Friedman points to a reluctance in the Arab world to address the issue of Arab Jews and their expulsion. He argues that this is partly why “Umm Haroun” has sparked such fierce debates: “the expulsion of around a million Jews from Arab countries in the 50s and 60s has been considered, until recently, a forbidden topic.” Friedman finds the show significant to Israelis not only for its political implications, as Al Jazeera argued, but for its frank depiction of an Arab Jewish community. This opinion did not make it into the Al Jazeera article.

Arab Jews, for the most part, no longer remain in the Arab world. Memories of their presence—and their expulsion—do. These memories are potent enough to generate hundreds of opinion pieces about Arab Jews, but not potent enough to spur their inclusion in the shows and conversations that revolve around them. “Umm Haroun”'s attempt to resurrect the history of Arab Jews in the Gulf and Al Jazeera’s attempt to bring Israeli voices into the media conversation do not adequately include the voices, opinions, thoughts, and experiences of real Arab Jews, despite their centrality to both the show and the controversy.

Watching the show, one cannot help but see the fierce controversy about Arab Jews, and their absence from that conversation, as a real-life reflection of the interpersonal, religious, and political conflicts Umm Haroun forewarns in the historical drama. “Umm Haroun” elicited an important reckoning with the history of Arab Jews, but any deeper healing of scars left by the expulsion of these Jews must include their voices.

//MAYA BICKEL is a junior in Columbia College and Features Editor at The Current. She can be reached at [email protected].

Photo courtesy of MBC

The Saudi-produced TV show “Umm Haroun” (literally “mother of Aaron,” named after its main character) follows a Jewish nurse in an unnamed Gulf country in the 1940s and the relationships that unfold between her family and their Christian and Muslim neighbors. Even before this new TV show aired in April 2020, it was the subject of heated debates across the Arab world that offers a view into the complicated opinions held about Jews and Israel. Although the show’s controversy centers on Jews who were forced out of Arab lands following the creation of the State of Israel, those Jews are left out of the conversation.

The show’s critics consider these Jews, many of whom are now Israeli citizens, stand-ins for the State of Israel. Any sympathetic portrayal of them on TV is equivalent to a sympathetic portrayal of Israel. Even more concerning to the critics is the show’s portrayal of Jews as victims of discrimination and, early on in the show, extreme violence: a Jewish man is murdered soon after the village finds out about the creation of the State of Israel. The victimization of the Jewish characters is seen as a betrayal of the Palestinian cause and a blatant attempt to normalize relations with Israel.

The show’s supporters, on the other hand, praise it for addressing a long overlooked part of Arab history, that of thriving Jewish communities throughout the Middle East and North Africa. “Umm Haroun” paints the Jewish characters as Arab—just as Arab as their Muslim and Christian counterparts, even though they wear Star of David necklaces and prayer shawls. Hayat al-Fahad, the Kuwaiti actress who plays Umm Haroun, said in an interview with Kuwaiti newspaper Al-Anba that she chose to act in this show “because it deals with a group of people who were and still are in our world.” “It is true that we are no longer with them, but we must reach them through this older time period because we have a generation of youth who have no information on them,” she added.

Despite the show’s sympathetic portrayal of Arab Jews, it does not seem to have consulted Arab Jews, or any Jews, very carefully. Hebrew sentences are full of mistakes and Hebrew is depicted as being written from left to right. The show also portrays the Jewish community as large when in fact Jewish communities in the Gulf were relatively small. The show’s inability to communicate directly with the community it tries to portray further highlights the societal rifts that have emerged since these Jews’ expulsion.

Since the show was not entirely successful at integrating the actual voices of Arab Jews, it is unsurprising that attempts by the media to include Jewish voices were also unsuccessful. An Arabic Al Jazeera article titled “The Demise of Israel and the Legitimization of Normalization: How Did Israeli Media Read the Ramadan TV Dramas?” attempts to bring Israeli perspectives on the controversy into the media conversation. The attempt reveals a curiosity among some corners of Arabic language media over how Israel and its citizens, some of whom are Arab Jews, are thinking about the controversy. But the article that results is far from an accurate reflection of Israeli opinions on the show.

The Al Jazeera article argues that, all in all, Israeli media looks favorably upon the TV show, quoting the Arab affairs commentator of KAN, an Israeli state-owned TV channel, and Yaron Friedman, Arab affairs commentator of Yediot Aharonot, one of Israel’s two leading dailies. According to Al Jazeera, this favorable outlook stems from their perception of “Umm Haroun” as a sign of changes in the Arab world that are bringing certain countries closer to Israel. However, Al Jazeera misreads Friedman’s article, in ways both deliberate and inadvertent, and only includes quotes that support this understanding of the politics-focused Israeli reception.

According to the Al Jazeera article, “Dr. Yaron Friedman, Arab affairs commentator for the newspaper Yediot Aharonot thinks that the show Umm Haroun sends a political message that ‘Gulf countries are paving the way towards normalization with Israel.’” Al Jazeera, perhaps inadvertently, left out the crucial beginning of Friedman's sentence. In the original Hebrew article Friedman writes, “according to its critics, the show Umm Haroun....” (emphasis added). Friedman’s article quotes opinions found in Arab media about the show. Al Jazeera, though, uses his quote as an example of an opinion found in Israeli media.

This opinion is in fact expressed in other parts of Friedman’s article, but the use of the misquote suggests that Friedman’s article was quickly scoured for quotes that fit a certain narrative of Israeli responses. Since Al Jazeera’s article focuses on Israel’s positive reception of “Umm Haroun” and its embrace of the show’s geopolitical significance, it is no surprise that Al Jazeera also deliberately chose not to include one of Friedman’s main points.

His article is titled “The Jews are also victims: The Israeli Storm in the Ramadan Shows,” and analyzes the controversy over “Umm Haroun” for its geopolitical significance and also for its significance for Arab Jews. Friedman points to a reluctance in the Arab world to address the issue of Arab Jews and their expulsion. He argues that this is partly why “Umm Haroun” has sparked such fierce debates: “the expulsion of around a million Jews from Arab countries in the 50s and 60s has been considered, until recently, a forbidden topic.” Friedman finds the show significant to Israelis not only for its political implications, as Al Jazeera argued, but for its frank depiction of an Arab Jewish community. This opinion did not make it into the Al Jazeera article.

Arab Jews, for the most part, no longer remain in the Arab world. Memories of their presence—and their expulsion—do. These memories are potent enough to generate hundreds of opinion pieces about Arab Jews, but not potent enough to spur their inclusion in the shows and conversations that revolve around them. “Umm Haroun”'s attempt to resurrect the history of Arab Jews in the Gulf and Al Jazeera’s attempt to bring Israeli voices into the media conversation do not adequately include the voices, opinions, thoughts, and experiences of real Arab Jews, despite their centrality to both the show and the controversy.

Watching the show, one cannot help but see the fierce controversy about Arab Jews, and their absence from that conversation, as a real-life reflection of the interpersonal, religious, and political conflicts Umm Haroun forewarns in the historical drama. “Umm Haroun” elicited an important reckoning with the history of Arab Jews, but any deeper healing of scars left by the expulsion of these Jews must include their voices.

//MAYA BICKEL is a junior in Columbia College and Features Editor at The Current. She can be reached at [email protected].

Photo courtesy of MBC