//essays//

Spring 2019

Spring 2019

A long way from Frankfurt:

A Response to “Intermarriage and Conservative Judaism”

Anonymous

The article “Intermarriage and Conservative Judaism: A Debate on the Sanctity of Jewish Marriages,” published in The Current Fall 2018, provides a competent summary of today’s debate around intermarriage in the Conservative movement. I know the author to be a thoughtful person, and it is above all a privilege to be in dialogue with him. The seriousness with which he treats his subject is evident throughout, and the piece includes helpful quotes from figures involved in this debate.

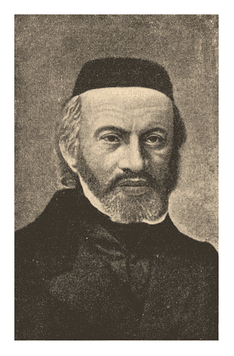

The article also—with less success—attempts to compare the 21st-century American-Jewish dispute over intermarriage to the 1845 German-Jewish dispute over Hebrew in liturgy, and particularly Zecharias Frankel’s role therein. Historically, this aspect of the article is slightly unfair, prompting my response. The author suggests that the leaders of German reform were a) deficient scholars who were b) in thrall to the Jewish masses. In fact, the reform leaders were (like Frankel) excellent rabbinic scholars who largely (unlike Frankel) placed little stock in the opinions of the Jewish masses. I will address these errors in turn, in the hope to rectify what are admittedly common misconceptions.

The author characterizes the 1845 Frankfurt conference by saying that “Frankel was alarmed by the Reformers’ ignorance of Jewish law.” The leaders of German Reform were not ignorant of Jewish law. We need not look far to see this: Abraham Geiger, the driving force behind the rabbinical conferences of the 1840s and the foremost leader of German Reform, was a rabbinic scholar of such high caliber that even his traditionalist rivals had to admit his ingenuity. For his elegant chiddush on the order of the tractates in the Mishnah, Geiger won the enthusiastic praise of the Italian scholar Samuel Luzzatto (Shadal) and the grudging respect of the Galician rabbi Solomon Rapoport.

Nor did Frankel believe the reformers to be ignorant of Jewish law. His magnum opus, Darkhei HaMishnah, is riddled with citations praising of Geiger’s rabbinic scholarship.

Nor, finally, was the dispute between Frankel and the reformers on Hebrew in liturgy a dispute about Jewish law at all. Frankel joined the majority of the Frankfurt conference in affirming that Jewish law did not require Hebrew as the language of public prayer—the reformers read the sources correctly—but argued to keep Hebrew for historical and sentimental reasons.[1]

The author, unfortunately, is neither the first nor the last to link present-day liberal-Jewish trends to the invented textual incompetence of 19th-century German reform leaders. A similar trick was tried last year in a book against tikkun olam; scholar Shaul Magid refuted it in that context, demonstrating that the German reformers were “highly trained scholars in the Hebrew Bible and rabbinics” rather than, as that author held, “meddling liberal rabbis who knew a smattering of the Hebrew Bible.” The enduring myth that 19th-century German reform was born in ignorance is so frustrating because it amounts to an ahistorical, petty, and, well, ignorant intra-religious polemic.

The author’s other major error in his article for The Current, more curious than offensive, is on the role of populism vs. elitism in the Frankfurt conference. He writes that “to the Reform rabbis, the strict rabbinic courts and more observant Jewish communities were ignoring the large number of European Jews who were abandoning Jewish practice.” By contrast, he claims that Frankel left the Frankfurt conference in a refusal to “make religious concessions to conform to the sociological status quo.”

But the author has it entirely backwards. Frankel aligned himself with the Jewish masses, while the reformers were consciously niche but committed idealists. It is no hyperbole to say that for Frankel, more than any Jewish thinker before or after, the sociological status quo is that which is religiously normative. The law, like a language, is distinctive to and determined by the Jewish nation; popular observance, or lack thereof, is the operative factor in deciding whether to keep a given ritual. The halakha is grounded in the behavior of the Jewish nation, and the nation’s will cannot be defied by rabbis from above.

The reform leadership took Frankel to task for this populist philosophy of halakha. Dr. Joseph Maier championed the cause of reform against Frankel, declaring that “the revealed will of God is the incontestable standard for reforms, not the will of a party, even though that party forms for now an overwhelming majority.”[2] Both Frankel and the reformers believed the masses to be on Frankel’s side; they disagreed only as to what consequences that fact had for law.

The characterization of 19th-century leaders of German Jewish Reform as unlettered populists is so powerfully contrary to the historical record that one begins to wonder whether it arises from a retrojection of the author’s assessment of 21st-century American Jewry. Of course, that retrojection itself becomes academically interesting. One best appreciates the essay by analogizing, on the one hand, its relationship to historical 19th-century Germany to, on the other hand, the imaginative relationship of Milton Steinberg’s novel As a Driven Leaf to 2nd-century Palestine: some of the characters are the same and the setting is right, but we ultimately learn less about history than about a particular set of American-Jewish anxieties.

I hope to have avoided touching directly on those anxieties in this response. I do not seek to weigh-in on the first-order issue of intermarriage in the Conservative movement, but only to communicate why the 19th-century German dispute over the language of prayer makes such a poor analogue. This time around, the masses are the cosmopolitans, while the virtues of endogamy are argued for mainly by a rabbinic elite.

I am confident that the growing will to intermarriage in the Conservative movement is not being masterminded by, say, some rationalist JTS professor enamoured of Hermann Cohen (mainly because I know said professor and doubt he is hiding a project of that scale). Rather, it springs from the quiet crevices of Jewish domestic life—the rabbi standing face-to-face with her hopeful congregant, the parent wanting to see his child married under a chuppah—until such a will grows, as Frankel described the halakha itself, “from a trickle into a rich and raging river.”[3] Frankel was certainly invested in the national distinctiveness of the Jewish people, but he just as certainly thought it wrongheaded folly for a rabbinic elite to defy the ritual practice of its constituents.

American Jewry resembles not the real or imagined pious multitudes of Frankel’s Germany, but rather—and I include myself in this characterization—a deracinated set of autonomous individuals, failed educationally by a Jewish establishment whose primary concern is the ethnic perpetuation of the Jewish people. I do not envy the present leaders of Conservative Jewish institutions, who face no easy options. I hope only to have established that those who are irritated by the existence of learned assimilationists will find no balm in Frankfurt, and those who seek to deny the wisdom of the Jewish masses will find no succor in Zecharias Frankel.

[1] See Ismar Schorsch, From Text to Context, p. 258, drawing from the Frankfurt Conference's minutes in “Protokolle und Aktenstücke der zweiten Rabbiner-Versammlung.”

[2] Philipson, David. “The Rabbinical Conferences, 1844-6.” The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, July 1905, pp. 681-682.

[3] Frankel, Vorstudien zu der Septuaginta, 1841, p. xii. Translation that of Ismar Schorsch, “The Ethos of Modern Jewish Scholarship,” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook, 1990, p. 67.

[2] Philipson, David. “The Rabbinical Conferences, 1844-6.” The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, July 1905, pp. 681-682.

[3] Frankel, Vorstudien zu der Septuaginta, 1841, p. xii. Translation that of Ismar Schorsch, “The Ethos of Modern Jewish Scholarship,” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook, 1990, p. 67.

//Any response to anonymous please reach out to editors.columbiacurrent@gmail.com.

Photo courtesy of Google Images.

Photo courtesy of Google Images.