//features//

Spring 2021

Spring 2021

Jewish Writers, Antisemitic Characters

Alyx Bernstein

“Money, please!” Mona-Lisa Saperstein whines, smashing up her father’s office when she is rebuffed. In another scene of the show Parks and Recreation, Mona-Lisa asks again for money, which her father obliges. Her ex-boyfriend Tom Haverford tells him, “Your daughter needs to be locked up in some sort of an insane asylum. On an island. In space.”

The Sapersteins are blatantly antisemitic. Mona-Lisa’s tacky clothing, obsession with money, implied mental illness, and high-pitched nasal voice are drawn straight from the worst stereotypes about American Jewish women, while her brother Jean-Ralphio’s character plays on age-old stereotypes of Jewish men as untrustworthy, effeminate, and––most of all––annoying. Their father, who spoils them rotten, is a doctor. All three Parks and Recreation characters, though, are played by Jewish actors: Jenny Slate, Ben Schwartz, and Henry Winkler. One of the show’s co-creators, Michael Schur, is also Jewish. The inevitable question that comes up when watching Parks and Rec is why include these stereotypes? Schur, Slate, Schwartz, and Winkler are Jews, yet they are regurgitating some of the worst images of Jewish people. Parks and Rec is not alone in this. How can we understand this disturbing phenomena, and what does it mean for the Jewish characters we know and love?

A similar phenomenon plays out in the DC TV animated show Harley Quinn, which has a creative team dominated by Jews. The titular character has long been portrayed as Jewish ever since her introduction in Batman: The Animated Series. Her solo show also portrays her as Jewish, but the show’s depiction of Jews is incredibly disturbing. When Harley goes to the bar mitzvah of the Penguin’s nephew, the theme is money. The Penguin isn’t Jewish in the comics, but he is a money-hungry, hook-nosed villain, and the show's creators “went out of their way to reinvent his roots.” The result: plain antisemitism. Glee and Friends, two iconic comedies created by Jews, both have been criticized for their stereotypical Jewish characters.

More recently, Marvel Studio’s WandaVision (also created by a Jew, Jac Schaeffer) was criticized for erasing Wanda Maximoff’s Jewishness. Maximoff was created by Jewish comic book duo Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, though she was not portrayed as Jewish until she was retconned to be the daughter of the iconic Jewish supervillain Magneto by writer Bill Mantlo (creator of the Israeli superhero Sabra). Wanda has been hailed as a groundbreaking and powerful Jewish (and Romani) woman, which is why her erasure in the MCU was painful for some. But taking a step back, is a mind-controlling witch really the best Jewish representation? Again, antisemitic tropes are embedded in Jewish characters.

Jews actually have a long history of writing antisemitic or stereotypical Jewish characters. These characters appear mostly in Jewish self-satire — comedies written by Jews that poke fun at Jews. Rachel Bloom’s musical TV show Crazy Ex-Girlfriend features Bloom as a Rebecca Bunch, a neurotic Jewish lawyer from a privileged Scarsdale family who self-identifies as a Jewish American Princess in one of the show’s most memorable songs (with an even more self-aware reprise). The show also features Tovah Feldshuh as Rebecca’s mother, who embodies the overbearing Jewish mother stereotype to a tee, storming in to criticize her daughter’s life choices, eating habits, dating life, and more. When Rebecca goes home to celebrate a bar mitzvah, the show parodies Jewish intergenerational trauma and Holocaust memorials. Andrew Goldberg and Nick Kroll’s Big Mouth takes a similar approach to Jewish self-parody; the show is full of self-deprecating jokes shared between the Jewish characters. Some of these are riffing on antisemitic stereotypes — Andrew Glouberman and Nick Birch’s parents, for example, are certainly overbearing Jewish mothers and submissive Jewish fathers. However, other jokes are aimed at satirizing more internal parts of Jewish culture, like summer camp, Florida, and cantors. Marvelous Mrs. Maisel likewise features a lot of Jewish stereotypes — Midge (the protagonist) as the loud, outspoken Jewish American Princess, her ex-husband Joel as the ineffectual and passive Jewish man, her father Abe as the stingy Jewish intellectual, and her mother Rose as the overbearing Jewish mother. Yet the show also features non-stereotypical Jews, especially Midge’s manager Suzie, and like the other two shows, Maisel parodies internal Jewish culture, like the lengthy and humorous retreat into the Catskills, where many wealthy Jewish families summered in the 1950s. Another show in this mold is Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer’s Broad City, which has an entire episode parodying Birthright trips full of Jewish stereotypes.

Another common element of these shows is that the main characters — Rebecca Bunch, Andrew Glouberman, Nick Birch, Abbi Jacobs, and Ilana Wexler — are all thinly-veiled self-inserts by their creators. When asked about Jewish stereotypes on Maisel, the show’s creator Amy Sherman-Palladino defended the choice, noting that she based many of the characters on her family and people she knew; after all, Sherman-Palladino’s mother was a Catskills-dwelling Jewish comic.

This sort of Jewish self-satire appears in dramas as well. Joey Solloway’s Transparent and Ilene Chaiken’s The L Word feature characters taken straight from the creator’s lives and explore Jewish trauma with Jewish characters who fit antisemitic stereotypes of Jews. As Gina Abelkop writes, The L Word’s Jenny Schecter embodies the “shrill hysteria, entitled arrogance, nagging, confused identity” stereotypical of Jewish women, with an entire plotline where she goes home to her suburban Chicago home (in Skokie) and explores her trauma. Jenny is near-universally loathed by The L Word fans. Her “Jewish” traits are a part of that.

Some of these shows, especially Maisel, have been criticized for their inclusion of antisemitic stereotypes. But when Rachel Bloom is writing songs about Holocaust memory and including “sheket bevaka-shut the fuck up” in her songs, the audience for these jokes is clearly a Jewish one. Broad City’s Birthright episode only really lands if you are familiar with Birthright. When Midge is talking about Yom Kippur, the audience is, again, a Jewish one. For Jews writing about themselves and their lives, are stereotypes a useful analytic tool? Stereotypes can be reductive and offensive, but they are often traits of real people. Jews consuming these shows may find these characters relatable and enjoy the self-deprecating humor, though this is not universal.

Yet these shows, characters, and stories, aimed as they are at Jewish audiences, are also consumed by non-Jews. When these stereotypical characters are such a common motif in Jewish representation on TV, it seems like it would be easy for viewers to internalize some of the antisemitic stereotypes portrayed on these shows. Jews writing Jewish stereotypes is not new, of course. Herman Wouk’s 1955 book Marjorie Morningstar is credited with shaping the Jewish American Princess stereotype, as are Philip Roth’s books.

That is not to say all Jews written by Jews are necessarily antisemitic stereotypes. Brooklyn 99’s Jake Peralta and The West Wing’s Josh Lyman and Toby Ziegler do not fit easily into common stereotypes about Jews. Jake somewhat fits the Nice Jewish Boy stereotype, but this is undermined by his role as a police officer (interestingly, the Brooklyn 99 creator Michael Schur is also the creator of Parks and Rec. While Josh and Toby are “coastal New York elites,” the show points out the antisemitism of this in the pilot, and their characters are not really Jewish stereotypes beyond that setup. The West Wing even features an entire cold open written in Yiddish, but it’s about Jewish gangsters, not some Jews wandering around a shtetl. The CW’s Arrowverse, which has several Jews on the creative staff, features several Jewish characters that are not particularly stereotypical (though one does get murdered by a Nazi). In film, The Big Lebowski’s Walter Sobchak is visibly Jewish but not at all a stereotype.

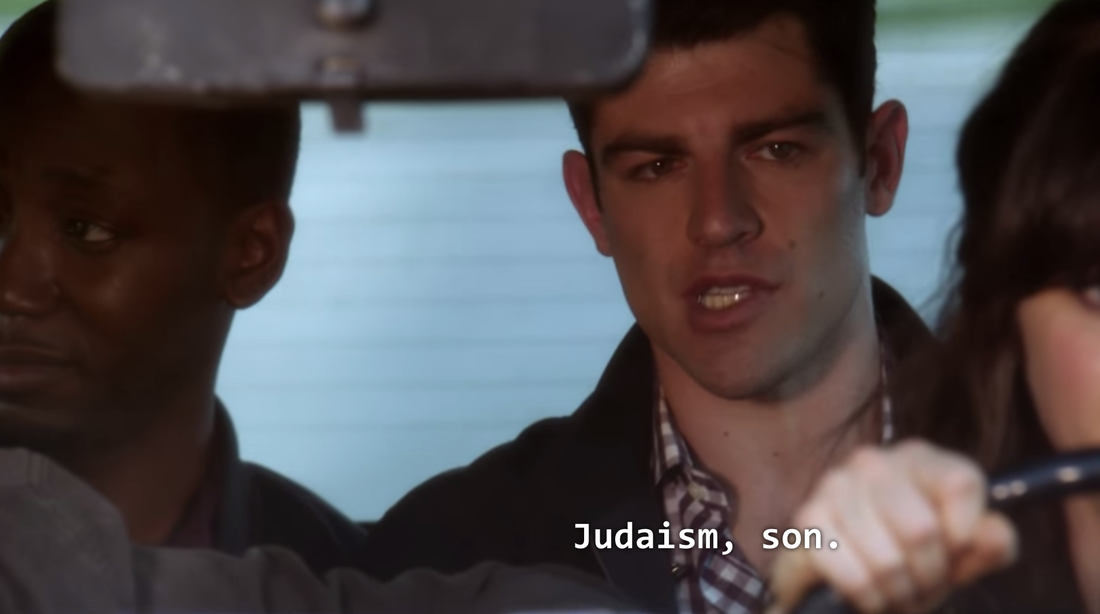

One character who toes the line of stereotype is New Girl’s Winston Schmidt, created by Elizabeth Meriwether (a Jew). Schmidt is perhaps most identifiable in the “Judaism, son!” GIF from the show’s first season. He is vocally Jewish, though his looks are often insulted by reference to his Judaism. Schmidt is also emasculated by his female coworkers, and two of his defining traits are his insecurity about his masculinity and his neuroticism — all classic stereotypes of the submissive, emasculated, insecure Jewish man. The show devotes real time to unpacking these things, exploring his complicated relationship with his family, his anxiety, and most of all his masculinity. The show deepens his character by dealing with his stereotypical traits. They also accurately portray Jewish mourning customs (albeit for a cat), insert Yiddish naturally into Schmidt’s casual speech, talk about his bar mitzvah, and even show rabbis getting into a brawl. Yes, Schmidt is stereotypical, but the show addresses these stereotypes and still offers a character who is proudly Jewish.

Any survey of Jewish characters written by Jews will include nuanced characters like Schmidt, self-parody like Nick and Andrew, and some characters who are just plain offensive (the Sapersteins). What makes a character feel offensive is to some extent subjective. But when examining Jewish characters and stereotypes, it is clear that not all stereotypical characters are created equal, and not all of them are bad or offensive. There is room for stereotypes on Jewish TV, whether it is to laugh at ourselves, to unpack and explore those stereotypes, or some combination of the two.

//ALYX BERNSTEIN is a sophomore in Barnard College and the Jewish Theological Seminary and editor at The Current. She can be reached at [email protected].

Photo from season 1, episode 9 of New Girl, taken from https://www.heyalma.com/the-story-behind-our-favorite-jewish-gif/