//essays//

Fall 2018

Being Jewish at Barnard:

A Retrospective

Miriam Lichtenberg

Ruth Saberski Goldenheim was celebrating; the year was 1935 and she and her fellow classmates were feeling the excitement of graduation. While some of her friends were unsure of what came next, Goldenheim was anxious to embark on her yearlong fellowship in Spain, where she would be given an opportunity to deepen her Spanish studies. Before making her final departure from the halls of Barnard, Goldenheim was asked to stop by her dean’s office. She previously had only intermittent interactions with Dean Virginia Gildersleeve—her living accommodations near the deanery made it so that she would see the dean every once in a while. The excitement of the time was short-lived; Dean Gildersleeve wanted only to remind Goldenheim that she will be going abroad as an American, not a Jew. Goldenheim was deeply embarrassed. It was not until sixty years later when she attended a Barnard event with her recently Barnard graduated granddaughter, Janet Alperstein, that she first shared that story. (1)

Eleanor Meyers was a Jewish student at Barnard during the years 1911-1914. In her scrapbook, she documents a note written to newly minted Dean Gildersleeve by a former chairman of the chapel committee. This letter was written in regards to the upcoming lecture given by Rabbi Stephen Wise, being held in the chapel. The letter writes: “I thought Barnard would go to pieces after 1912 had left it; now I know it!!!” In response to this outlandish anti-Semitism, Gildersleeve attempted to placate the writer of the note: “Cheer up! They just happen to be “[...].” There haven’t been any more! VCG." (2)

These stories are telling, deeply upsetting, and yet, not too shocking. That Dean Gildersleeve, as well as her institution leaned, towards antisemitism was well known. Gildersleeve’s antisemitism was not unique, though, in her role as dean of Barnard from 1911-1946, it was extremely pervasive in ways that are still reminiscent to this day.

It was during the early 1920s that Barnard first articulated that it was experiencing a “Jewish Problem,” namely the influx of many academically qualified Jewish applicants, as the Jewish community of New York City expanded. Gildersleeve was not too pleased with what she—and others in her position—saw as a Jewish invasion of higher education. The Jewish students of New York were hardly seen as the ideal student, and in fact were anathema to an understanding of the “qualified” student, who was dignified in social class and character.

In its uniquely situated location, however, Barnard found that it was attracting two types of students, and with that two types of Jewish students; the rich and the poor. These students were not found at other Women’s colleges, such as Smith or Vassar, as “the young woman of modest means unable to afford the added expense of Bard at the ‘country college [yet] those from wealthy [were] backgrounds unwilling to forget the pleasures of New York society in their debutante years.” (3)

Initially, women from German and Spanish Jewish populations, attending from wealthy homes, were the Jews attending Barnard and their presence was even welcomed. Their assimilation into Barnard was easy, and they were received enthusiastically. By the Gildersleeve years, however, Jewish students from poorer backgrounds were making their way to the ivory tower, described as “a most unwelcomed community of students, many of Eastern European descent.” (4) Gildersleeve was deeply embarrassed by this.

Gildersleeve was aware of Barnard’s history, that it was largely started due to the efforts of Jewish woman Annie Nathan Meyer. As Barnard became increasingly embarrassed of its Jewish student body, however, it actively tried to quiet the significance of Jewish support in its early years. Meyer herself, when advocating for the founding of Barnard, understood that using herself as the namesake would only serve to alienate those who would not attend an institution named after a Jew. Gildersleeve did not find Meyer’s Jewishness to be a challenge to the anti semitism Gildersleeve brought to Barnard. As Gildersleeve wrote in a letter to Meyer, “Many of our Jewish students have been charming and cultivated human beings. On the other hand, as you know, the intense ambition of the Jews for education has brought to college girls from a lower social level than that of most of the non-Jewish students. Such girls have compared unfavorably in many instances with the build of the undergraduates.” (5) That Meyer was Jewish was not a contra- diction; she was a “good” Jew. Fewer and fewer Jews like her were populating Barnard.

However, the antisemitism did extend to other founders. In the early 20th century, philanthropist and trustee member Jacob Schiff was courted to donate money to a building that would allow Barnard students to congregate. Schiff found this to be a worthwhile donation, but Barnard did not ultimately find him to be a worthy donor: “...when the trustees renamed Students’ Hall, they did not give it Schiff ’s name, but called it Barnard Hall, much to the anguish of Annie Nathan Meyer, who campaigned unceasingly to remove the impression the ‘the College is unwilling to place upon one of its building the name of a Jew.’” (6) To this day, students pass through Barnard Hall unaware of the erasure its name is founded upon.

Jewish students at the time, however, were aware of this; they were aware that they weren’t welcomed, aware that their institution was not their advocate and hopeful that even so, education, and a prestigious education at that, was their way to escape the antisemitism they faced. On nearly all college campuses, especially in the Ivy Leagues, Jews were excluded from mainstream clubs and organizations. Jewish students wanted to rectify this problem by creating their own social network.

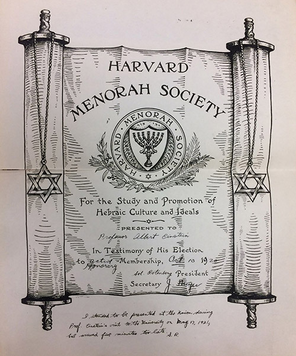

Thus began the Menorah Society, a sort of predecessor to the modern day Hillel. “The roots of the Menorah movement lay in the yearning of young men and women for the ‘New Judaism’...” I.e. the Jew who would be seen and accepted as a qualified student. Originally beginning at Harvard, this organization spread like wildfire. Jewish students wanted a place that would be “devoted to the study of Jewish history, literature, religion, philosophy, jurisprudence, art, manners, in a word, Jewish culture, and to the academic discussions of Jewish problems.” Jewish students wanted to preserve their Jewish identity, but were finding it hard in the face of pervasive antisemitism. Thus, the Menorah Society hoped to advance “the educational activities of the Jews of NYC in light of their relation to American national aspirations, as the activities of a community that wishes to preserve its group life in this country.” (7) Coming to Barnard, these students were most likely coming from homes that were constantly struggling with how to balance their religious preservation and American assimilation.

The Columbia/Barnard Menorah Society was unique in its access to prestigious Jewish thinkers. Speakers were often invited to address the question of the Modern American Jew in the face of antisemitism. (8) Speakers such as David de Sola Pool, Rabbi of the Spanish Portuguese synagogue in Manhattan, who gave a lecture titled “The traditional Judaism as the best alternative” addressing how traditional Judaism is necessary for the Jewish continuity. Speakers tended to disagree on the correct tactic to face the prevalence of antisemitism. In contrast to Rabbi de Sola Pool, Rabbi Goldenson, Rabbi of Temple Emanu-El and regarded as one of the foremost Jewish leaders, argued for “Reformed Judaism as Our Hope for the Future” at a tea talk. The students, as well as speakers, of the Menorah Society were simply grappling with what the future of the American Jew could and would look like. Other speakers included Dr. Harold Korn, Mordechai Kaplan, Mr. Morris Rothernberg (former president of the Zionist organization of America), Dr. Robert Gordis, Rabbi Steinberg of Park Ave and Mr. Jacob Weinberg. In this sense, The Columbia/ Barnard Menorah Society was very lucky to be located in the cultural acropolis that was Manhattan, with the Jewish Theological Seminary just a few blocks uptown.

Much of what the Menorah Society attempted to achieve was to combat the idea that the Jew was in any way inferior, an understanding that Jews were internalizing to a great extent. In a 1936 publication of the Barnard Bulletin, Miriam Roehr, herself a Jew and a member of the Menorah Society, begged her fellow students to not carry so much hate for this man named Hitler—it was not healthy for the modern Barnard student. The extent of Jewish repression cannot be more overt.

In recent months, I have seen much of the Columbia University Jewish community rally against Barnard as an antisemitic institution, citing that they feel unsafe as a Jewish student on campus. I deeply sympathize with such claims, as I do believe that the experience of the American Jew has dramatically changed in light of recent events. I cannot, however, agree that Barnard as an institution would ever support antisemitic rhetoric. Of course, to say that Barnard would not enact the same antisemitism it once did is not a wonderful compliment to give. But beyond that, I think Barnard actively supports its students regardless of religion. As a Jewish student on campus, I feel entirely safe in the cocoon of my Morningside Heights bubble.

Eleanor Meyers was a Jewish student at Barnard during the years 1911-1914. In her scrapbook, she documents a note written to newly minted Dean Gildersleeve by a former chairman of the chapel committee. This letter was written in regards to the upcoming lecture given by Rabbi Stephen Wise, being held in the chapel. The letter writes: “I thought Barnard would go to pieces after 1912 had left it; now I know it!!!” In response to this outlandish anti-Semitism, Gildersleeve attempted to placate the writer of the note: “Cheer up! They just happen to be “[...].” There haven’t been any more! VCG." (2)

These stories are telling, deeply upsetting, and yet, not too shocking. That Dean Gildersleeve, as well as her institution leaned, towards antisemitism was well known. Gildersleeve’s antisemitism was not unique, though, in her role as dean of Barnard from 1911-1946, it was extremely pervasive in ways that are still reminiscent to this day.

It was during the early 1920s that Barnard first articulated that it was experiencing a “Jewish Problem,” namely the influx of many academically qualified Jewish applicants, as the Jewish community of New York City expanded. Gildersleeve was not too pleased with what she—and others in her position—saw as a Jewish invasion of higher education. The Jewish students of New York were hardly seen as the ideal student, and in fact were anathema to an understanding of the “qualified” student, who was dignified in social class and character.

In its uniquely situated location, however, Barnard found that it was attracting two types of students, and with that two types of Jewish students; the rich and the poor. These students were not found at other Women’s colleges, such as Smith or Vassar, as “the young woman of modest means unable to afford the added expense of Bard at the ‘country college [yet] those from wealthy [were] backgrounds unwilling to forget the pleasures of New York society in their debutante years.” (3)

Initially, women from German and Spanish Jewish populations, attending from wealthy homes, were the Jews attending Barnard and their presence was even welcomed. Their assimilation into Barnard was easy, and they were received enthusiastically. By the Gildersleeve years, however, Jewish students from poorer backgrounds were making their way to the ivory tower, described as “a most unwelcomed community of students, many of Eastern European descent.” (4) Gildersleeve was deeply embarrassed by this.

Gildersleeve was aware of Barnard’s history, that it was largely started due to the efforts of Jewish woman Annie Nathan Meyer. As Barnard became increasingly embarrassed of its Jewish student body, however, it actively tried to quiet the significance of Jewish support in its early years. Meyer herself, when advocating for the founding of Barnard, understood that using herself as the namesake would only serve to alienate those who would not attend an institution named after a Jew. Gildersleeve did not find Meyer’s Jewishness to be a challenge to the anti semitism Gildersleeve brought to Barnard. As Gildersleeve wrote in a letter to Meyer, “Many of our Jewish students have been charming and cultivated human beings. On the other hand, as you know, the intense ambition of the Jews for education has brought to college girls from a lower social level than that of most of the non-Jewish students. Such girls have compared unfavorably in many instances with the build of the undergraduates.” (5) That Meyer was Jewish was not a contra- diction; she was a “good” Jew. Fewer and fewer Jews like her were populating Barnard.

However, the antisemitism did extend to other founders. In the early 20th century, philanthropist and trustee member Jacob Schiff was courted to donate money to a building that would allow Barnard students to congregate. Schiff found this to be a worthwhile donation, but Barnard did not ultimately find him to be a worthy donor: “...when the trustees renamed Students’ Hall, they did not give it Schiff ’s name, but called it Barnard Hall, much to the anguish of Annie Nathan Meyer, who campaigned unceasingly to remove the impression the ‘the College is unwilling to place upon one of its building the name of a Jew.’” (6) To this day, students pass through Barnard Hall unaware of the erasure its name is founded upon.

Jewish students at the time, however, were aware of this; they were aware that they weren’t welcomed, aware that their institution was not their advocate and hopeful that even so, education, and a prestigious education at that, was their way to escape the antisemitism they faced. On nearly all college campuses, especially in the Ivy Leagues, Jews were excluded from mainstream clubs and organizations. Jewish students wanted to rectify this problem by creating their own social network.

Thus began the Menorah Society, a sort of predecessor to the modern day Hillel. “The roots of the Menorah movement lay in the yearning of young men and women for the ‘New Judaism’...” I.e. the Jew who would be seen and accepted as a qualified student. Originally beginning at Harvard, this organization spread like wildfire. Jewish students wanted a place that would be “devoted to the study of Jewish history, literature, religion, philosophy, jurisprudence, art, manners, in a word, Jewish culture, and to the academic discussions of Jewish problems.” Jewish students wanted to preserve their Jewish identity, but were finding it hard in the face of pervasive antisemitism. Thus, the Menorah Society hoped to advance “the educational activities of the Jews of NYC in light of their relation to American national aspirations, as the activities of a community that wishes to preserve its group life in this country.” (7) Coming to Barnard, these students were most likely coming from homes that were constantly struggling with how to balance their religious preservation and American assimilation.

The Columbia/Barnard Menorah Society was unique in its access to prestigious Jewish thinkers. Speakers were often invited to address the question of the Modern American Jew in the face of antisemitism. (8) Speakers such as David de Sola Pool, Rabbi of the Spanish Portuguese synagogue in Manhattan, who gave a lecture titled “The traditional Judaism as the best alternative” addressing how traditional Judaism is necessary for the Jewish continuity. Speakers tended to disagree on the correct tactic to face the prevalence of antisemitism. In contrast to Rabbi de Sola Pool, Rabbi Goldenson, Rabbi of Temple Emanu-El and regarded as one of the foremost Jewish leaders, argued for “Reformed Judaism as Our Hope for the Future” at a tea talk. The students, as well as speakers, of the Menorah Society were simply grappling with what the future of the American Jew could and would look like. Other speakers included Dr. Harold Korn, Mordechai Kaplan, Mr. Morris Rothernberg (former president of the Zionist organization of America), Dr. Robert Gordis, Rabbi Steinberg of Park Ave and Mr. Jacob Weinberg. In this sense, The Columbia/ Barnard Menorah Society was very lucky to be located in the cultural acropolis that was Manhattan, with the Jewish Theological Seminary just a few blocks uptown.

Much of what the Menorah Society attempted to achieve was to combat the idea that the Jew was in any way inferior, an understanding that Jews were internalizing to a great extent. In a 1936 publication of the Barnard Bulletin, Miriam Roehr, herself a Jew and a member of the Menorah Society, begged her fellow students to not carry so much hate for this man named Hitler—it was not healthy for the modern Barnard student. The extent of Jewish repression cannot be more overt.

In recent months, I have seen much of the Columbia University Jewish community rally against Barnard as an antisemitic institution, citing that they feel unsafe as a Jewish student on campus. I deeply sympathize with such claims, as I do believe that the experience of the American Jew has dramatically changed in light of recent events. I cannot, however, agree that Barnard as an institution would ever support antisemitic rhetoric. Of course, to say that Barnard would not enact the same antisemitism it once did is not a wonderful compliment to give. But beyond that, I think Barnard actively supports its students regardless of religion. As a Jewish student on campus, I feel entirely safe in the cocoon of my Morningside Heights bubble.

1. Taken from a phone interview with Janet Alperstein

2. Jewett, Eleanore Myers. “Eleanor Myers Jewett Scrapbook, Vol. 4, 1911-1912.” Scrapbooks, 1911, pp. 152 pages.

3. Wechsler, Harold S. The Qualified Student: A History of Selective College Admission in America. Taylor and Francis, 2017.

4. Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater Design and Experience in the Women's Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s. University of Massachusetts Press, 1993.

5. Ibid., 258

6. Ibid., 259

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid., 260

2. Jewett, Eleanore Myers. “Eleanor Myers Jewett Scrapbook, Vol. 4, 1911-1912.” Scrapbooks, 1911, pp. 152 pages.

3. Wechsler, Harold S. The Qualified Student: A History of Selective College Admission in America. Taylor and Francis, 2017.

4. Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater Design and Experience in the Women's Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s. University of Massachusetts Press, 1993.

5. Ibid., 258

6. Ibid., 259

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid., 260

//MIRIAM LICHTENBERG is a senior in Barnard College and a Senior Editor of The Current. She can be reached at [email protected].

Photo courtesy of: https://campaignforharvardhillel. com/

Photo courtesy of: https://campaignforharvardhillel. com/