//literary & arts//

Spring 2017

Chinatown's Synagogue

A Hidden Gem on Eldridge Street

Rebecca Jedwab

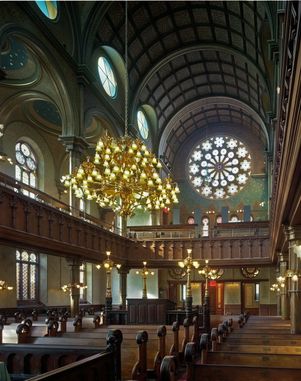

The main sanctuary in the Eldridge Street Synagogue.

The main sanctuary in the Eldridge Street Synagogue.

To a Barnard student nestled comfortably within Columbia’s campus at West 116th street, the Lower East Side of Manhattan seemed like an impossibly far away place—especially the day after a New York City snowstorm. As I trudged through the slush—passing tightly packed stores, fish markets, and laundromats in Chinatown—I struggled to locate the Museum at Eldridge Street. After a few wrong turns, I finally looked up to find a structure opposite me that more closely resembled a European synagogue than a New York museum. Its highly ornamented façade distinguished it from the neighboring brick buildings and its three sets of adjacent staircases elevated it above the surrounding community—aesthetically and structurally identifying the building as more than just another ordinary city edifice. The building that I had imagined to be tucked away in a secluded corner of Manhattan was suddenly impossible to overlook.

As the sole visitor to arrive for the 11:00 AM tour, I entered to find none of the characteristics that I have learned to associate with museums—there was no line at the welcome desk, no familiar buzz of people ambling through the galleries. This was a museum with no visitors. I realized immediately that the Museum at Eldridge Street is not a “museum” in the way that I have come to know and appreciate them.

Completed in one year and opened in 1887, the Eldridge Street Synagogue was the first synagogue built by Eastern European Jews who immigrated to the United States after escaping the pogroms of Eastern Europe. They filled the Lower East Side in large numbers, creating a growing community with kosher butcher shops and Jewish schools that populated the area’s crowded streets. Funded by four wealthy Jewish families, this synagogue was a communal institution, not only functioning as a place of worship, but also providing an environment of collective support for Jewish families in the area. The first stop on my tour was the lower level of the synagogue, a small and dimly lit room for daily prayer. It contains long wooden benches facing a bima (the raised platform from which the Torah is read) that stands in the center of the room and a large Torah ark further behind it, well-preserved and in use to this day by a small congregation of men. Intimate and authentic, the room felt like a private space to which I had been granted special access. Moreover, the little room rejects any temporal categorization: though remarkably functional today, it remains untouched by the passage of time. While religious objects are on display in small cases, including an original prayer book and prayer shawl from the 1800s, the room’s main features—the Torah ark and the bima—are not exhibited in glass cases, nor are there labels elucidating their history and purpose. They are not the sacrosanct items of a traditional museum display, which present objects as historical artifacts. Instead, they remain integrated with the architecture of the religious space, elements of American Jewish life whose functionality and beauty reverberate in the contemporary moment despite the 130 year distance from their making. The museum keeps them alive by refusing to put them in the coffers of a display case. These objects are not meant to be looked at; they are part of a rich and active religious tradition.

Where the lower level of the structure provides an intimate, humble space for Jewish worship, the upper level paints the picture of a thriving Jewish community on the Lower East Side of decades past. The building is an architectural marvel—bespeaking a rich cultural history that withstands the tides of a changing neighborhood. The synagogue’s beautiful main sanctuary is a much larger and more elaborately ornamented space than the lower level. It is surrounded on all sides by intricately designed stained-glass windows and covered by a decorated dome. With the capacity to hold hundreds of people, it was initially reserved for the High Holidays until a lack of funding made heating the room too great an expense and services were moved downstairs. Decades of disuse left the sanctuary inhabited by nesting pigeons; Torah scrolls were found sprawled across the floor when a two-decade renovation began in 1986 in order to restore the same structure that had famously been built in just one year.

Incredibly, almost every detail of the building was preserved, including the wooden benches, the wooden balcony that was reserved for women, the bima, and the Torah ark carved of imported Italian walnut. In accordance with European custom, the bima was kept in the middle of the room and the two smaller arks flanking the main Torah ark were left in their original positions. With the exception of a few changes, including the creation of a new stained-glass main window above the Torah ark, the sanctuary was restored to its original form. In its architectural preservation alone, the building remains fixed in the time period in which it was built.

And yet, it is not incorrect to call the synagogue a museum. By definition, museums are cultural centers that preserve and display pieces of historical, religious, and cultural significance. While the Eldridge Street Synagogue meets this criterion, it does not remove historical artifacts from their original contexts in order to present them to an audience as traditional museums often do. It is not simply an outer shell constructed to hold historically valuable objects: the history of the building and its contents are pieces of the same historical narrative. The preservation of the synagogue’s exterior and interior appearance reflects a commitment to maintaining its cultural legacy and decries a refusal to assimilate with the neighborhood around it or even to adopt modern aesthetics and modes of presentation. While it seems the institution prioritizes its religious function, the ideas of synagogue and museum cooperate symbiotically here, which ultimately imbues it with a sense of authenticity that traditional museums often lack.

On the upper balcony of the synagogue’s main sanctuary, a section of the wall remains unfinished and exposes the original layer of wood that lies beneath it. The fact that this portion of the wooden layer was not covered by a new one during the building’s massive restoration highlights the congregation’s intention to preserve the building’s original form rather than to remodel it completely. Ultimately, this section’s incompatibility with the rest of the sanctuary serves as a subtle reminder that the larger synagogue’s incongruity with its surroundings is precisely what makes the building so remarkable. Walking out of the near-empty synagogue and merging with the bustling crowd on the streets of Chinatown, now populated by a different immigrant community than the one the Eldridge Street Museum emerged from, I understood what the Museum at Eldridge Street means when it calls itself a museum: it is a time-capsule for a moment in New York Jewish history that politely refuses to relinquish its identity to the changing tides of its surrounding community.

As the sole visitor to arrive for the 11:00 AM tour, I entered to find none of the characteristics that I have learned to associate with museums—there was no line at the welcome desk, no familiar buzz of people ambling through the galleries. This was a museum with no visitors. I realized immediately that the Museum at Eldridge Street is not a “museum” in the way that I have come to know and appreciate them.

Completed in one year and opened in 1887, the Eldridge Street Synagogue was the first synagogue built by Eastern European Jews who immigrated to the United States after escaping the pogroms of Eastern Europe. They filled the Lower East Side in large numbers, creating a growing community with kosher butcher shops and Jewish schools that populated the area’s crowded streets. Funded by four wealthy Jewish families, this synagogue was a communal institution, not only functioning as a place of worship, but also providing an environment of collective support for Jewish families in the area. The first stop on my tour was the lower level of the synagogue, a small and dimly lit room for daily prayer. It contains long wooden benches facing a bima (the raised platform from which the Torah is read) that stands in the center of the room and a large Torah ark further behind it, well-preserved and in use to this day by a small congregation of men. Intimate and authentic, the room felt like a private space to which I had been granted special access. Moreover, the little room rejects any temporal categorization: though remarkably functional today, it remains untouched by the passage of time. While religious objects are on display in small cases, including an original prayer book and prayer shawl from the 1800s, the room’s main features—the Torah ark and the bima—are not exhibited in glass cases, nor are there labels elucidating their history and purpose. They are not the sacrosanct items of a traditional museum display, which present objects as historical artifacts. Instead, they remain integrated with the architecture of the religious space, elements of American Jewish life whose functionality and beauty reverberate in the contemporary moment despite the 130 year distance from their making. The museum keeps them alive by refusing to put them in the coffers of a display case. These objects are not meant to be looked at; they are part of a rich and active religious tradition.

Where the lower level of the structure provides an intimate, humble space for Jewish worship, the upper level paints the picture of a thriving Jewish community on the Lower East Side of decades past. The building is an architectural marvel—bespeaking a rich cultural history that withstands the tides of a changing neighborhood. The synagogue’s beautiful main sanctuary is a much larger and more elaborately ornamented space than the lower level. It is surrounded on all sides by intricately designed stained-glass windows and covered by a decorated dome. With the capacity to hold hundreds of people, it was initially reserved for the High Holidays until a lack of funding made heating the room too great an expense and services were moved downstairs. Decades of disuse left the sanctuary inhabited by nesting pigeons; Torah scrolls were found sprawled across the floor when a two-decade renovation began in 1986 in order to restore the same structure that had famously been built in just one year.

Incredibly, almost every detail of the building was preserved, including the wooden benches, the wooden balcony that was reserved for women, the bima, and the Torah ark carved of imported Italian walnut. In accordance with European custom, the bima was kept in the middle of the room and the two smaller arks flanking the main Torah ark were left in their original positions. With the exception of a few changes, including the creation of a new stained-glass main window above the Torah ark, the sanctuary was restored to its original form. In its architectural preservation alone, the building remains fixed in the time period in which it was built.

And yet, it is not incorrect to call the synagogue a museum. By definition, museums are cultural centers that preserve and display pieces of historical, religious, and cultural significance. While the Eldridge Street Synagogue meets this criterion, it does not remove historical artifacts from their original contexts in order to present them to an audience as traditional museums often do. It is not simply an outer shell constructed to hold historically valuable objects: the history of the building and its contents are pieces of the same historical narrative. The preservation of the synagogue’s exterior and interior appearance reflects a commitment to maintaining its cultural legacy and decries a refusal to assimilate with the neighborhood around it or even to adopt modern aesthetics and modes of presentation. While it seems the institution prioritizes its religious function, the ideas of synagogue and museum cooperate symbiotically here, which ultimately imbues it with a sense of authenticity that traditional museums often lack.

On the upper balcony of the synagogue’s main sanctuary, a section of the wall remains unfinished and exposes the original layer of wood that lies beneath it. The fact that this portion of the wooden layer was not covered by a new one during the building’s massive restoration highlights the congregation’s intention to preserve the building’s original form rather than to remodel it completely. Ultimately, this section’s incompatibility with the rest of the sanctuary serves as a subtle reminder that the larger synagogue’s incongruity with its surroundings is precisely what makes the building so remarkable. Walking out of the near-empty synagogue and merging with the bustling crowd on the streets of Chinatown, now populated by a different immigrant community than the one the Eldridge Street Museum emerged from, I understood what the Museum at Eldridge Street means when it calls itself a museum: it is a time-capsule for a moment in New York Jewish history that politely refuses to relinquish its identity to the changing tides of its surrounding community.

//REBECCA JEDWAB is a junior in Barnard College and a Contributing Writer for The Current. She can be reached at rj2367@barnard.edu. Photos courtesy of Robert Caplin for The New York Times.