//features//

Spring 2017

Coeducation Came to Columbia

Reflecting on 30 Classes of Columbia College Women

Hannah Stanhill

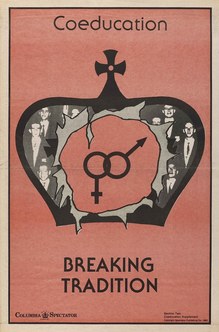

A 1983 Spectator supplement on coeducation. Courtesy of the Columbia University Archives.

A 1983 Spectator supplement on coeducation. Courtesy of the Columbia University Archives.

As the Columbia College Class of 2017 readies itself for graduation, its members may not realize that they mark the 30th coed class to graduate from the College. Thirty years ago, in May 1987, women received diplomas from Columbia College for the first time. Among these women were the class valedictorian, salutatorian, and class president. In their four undergraduate years, they had seen the addition of a women’s athletics program and a new induction into the Core Curriculum: its first female author, Jane Austen, added in 1985. Long overdue, the acceptance of women to Columbia College drastically improved the University’s status within the Ivy League and made admissions much more competitive. This change affected more than just Columbia College, though: Barnard College, the affiliate women’s institution, resisted incorporation into Columbia College and consequently had to adjust in order to survive.

The Decision to Go Coed

Maintaining an all-male class restricted Columbia’s ability to be as selective as the other Ivy League schools which had already gone coed. Columbia’s applicant pool was half that of other Ivies, meaning that it couldn’t be as discerning in who it admitted. Dr. Robert Pollack, (CC, ’61)—Professor of Biological Sciences since 1978 and Dean of the College from 1982-1989—oversaw the transition to coeducation. He notes, “Any kid who got into another Ivy school didn’t come to Columbia. Basically it was much more of a smart person’s safety school than a smart person’s competitive school.” Pollack believes that since Columbia was not coed, it was less selective, as it had twice as many spaces for male applicants as the other Ivies. This made it a less attractive choice for top-tier students.

In 1980, Arnold Collery, then Dean of the College, appointed a committee to look into the coed issue. The committee did some research and concluded in a report, published in April 1981, that Columbia College needed to admit women. As Robert McCaughey, Professor of History and Janet H. Robb Chair in the Social Sciences at Barnard College, put it, the report “contended that Columbia, if it was going to maintain any kind of standing within the Ivy League, better start recruiting women pretty fast.” Bolstered by this conclusion, and another within the report that Barnard College would be able to survive the change, Columbia’s faculty and trustees voted in the 1981-1982 academic year to begin accepting women.

Mark Lebowitz, (CC, ’86), a member of the last all-male class, recalls the sentiment among his fellow Columbia students that coeducation would make Columbia more selective. Many also thought that it would make the College more appealing, especially in an age when coed colleges were increasingly becoming the norm. Notwithstanding these advantages, there were many at Columbia, including Pollack, who simply believed that women should be admitted as a matter of principle.

Columbia accepted its first coed class for the fall of 1983; women comprised 45% of the class. Admitting female students immediately impacted Columbia’s selectivity, dropping its admissions rate from 40% for the class of 1986 to 31% for the class of 1987. McCaughey focuses on this particular result: “The first set of women and then on were at least as good as the typical Columbia student, so it lifted the whole. One way to look at it is that Columbia got rid of the bottom half of its class and replaced it with women who ranked with the students who were in the upper half.” Pollack, however, was more concerned with the fact that for the first time in 229 years, women could attend Columbia College. He hails the switch to coeducation as his greatest achievement as Dean. “How often does anybody get a chance to break a 200-year-old precedent and make it work?”

In going coed, Columbia leveled the playing field with other Ivies, but it remained to be seen how this decision would affect its long-time partner, Barnard College.

Balancing Barnard

Barnard College was founded in 1889 primarily in response to the fact that women could not attend Columbia College. Located directly across the street, Barnard was founded as a women’s college that would accompany Columbia and provide women with a similar caliber of education. Based on its original intent, the question arose: if Columbia went coed without including Barnard, would Barnard be able to survive as a women’s college, or would its reason for existence simply disappear? Columbia’s uncertainty about how coeducation would affect Barnard is part of the reason why it delayed this major decision for so many years.

Almost immediately, the possibility of Columbia College simply absorbing Barnard College, as Harvard College had done with Radcliffe College, was taken off the table. Barnard’s faculty voted to remain independent—they did not want to be swallowed up by Columbia. Pollack believes that “Barnard faculty did not want to teach in the Core, and that was why Barnard didn’t become the Radcliffe to Columbia.” He further contends that the Barnard faculty did not want to give up their academic trademark, the required senior thesis, for Columbia’s signature Core Curriculum. However, a different—more compelling—reason, was that Barnard faculty were employed separately from Columbia faculty, and if Barnard were to be combined with Columbia, many of them would lose their jobs altogether. This concern did not exist in the case of Harvard and Radcliffe because the two schools had always shared faculty.

According to Professor McCaughey, some Barnard students and faculty members, including himself, were “more disposed toward a merger than the institution was.” There were even some Barnard trustees in the early 1970s who were willing to accept a merger, but those trustees left the board by the early 1980s, before the coeducation question truly gained momentum. By the time of the critical vote in 1982, most of the trustees wanted Barnard to remain independent and believed that it was not in Barnard’s best interest for Columbia to become coeducational.

Still, in the early 1980s, before Columbia officially decided to admit women, alternative solutions were proposed. Barnard attempted to find an arrangement that would satisfy Columbia without it going fully coed. One of these possibilities was for Columbia to have “virtual coeducation.” This meant that it would have the same percentage of women in its classrooms as other Ivy Leagues, including Core classes (which had always been all-male), but without actually admitting women to Columbia College. However, this alternative would mean that women still could not be admitted directly to Columbia, so the coeducation issue was not really solved. Additionally, this solution would decrease the number of students enrolled in Barnard classes, since they would be busy taking Core classes at Columbia, decreasing the need for Barnard faculty and ultimately harming the school. As a result, this proposed solution did not garner much support, especially since the protection of its faculty was one of the main reasons that Barnard opposed the merger. Negotiations continued throughout the early 1980s to find an arrangement that would work for both sides of Broadway, but Barnard ran out of time: Columbia’s president, faculty, and trustees went ahead with coeducation anyway.

As expected, Barnard’s admissions suffered during the first few years after Columbia started accepting women. McCaughey theorizes that some women who previously would have gone to Barnard chose to attend Columbia instead, but after the first couple of years Barnard recovered. One possible explanation is that most women who were applying to Barnard were not deciding between Barnard and Columbia or between different Ivy League schools, but between Barnard and other women’s colleges.

Barnard effectively rebranded itself, playing up its status as a women’s college and its location in New York City, while also emphasizing its connection with Columbia. This unique marketing formula has allowed Barnard admissions to become more competitive each year. Barnard took full advantage of its affiliation with Columbia, but the cooperation between the two schools didn’t just benefit Barnard: Columbia took advantage of certain majors that were only offered at Barnard, such as dance and architecture, as well as utilizing Barnard’s help in developing its own women’s studies program.

Barnard also evolved as its own institution independent from Columbia. Qualities unique to Barnard include a strong focus on women’s and gender studies, a small and supportive community, and female empowerment. Barnard certainly took advantage of Columbia’s resources, but ultimately it thrived as a college in its own right and has survived based on its own merits.

The Decision to Go Coed

Maintaining an all-male class restricted Columbia’s ability to be as selective as the other Ivy League schools which had already gone coed. Columbia’s applicant pool was half that of other Ivies, meaning that it couldn’t be as discerning in who it admitted. Dr. Robert Pollack, (CC, ’61)—Professor of Biological Sciences since 1978 and Dean of the College from 1982-1989—oversaw the transition to coeducation. He notes, “Any kid who got into another Ivy school didn’t come to Columbia. Basically it was much more of a smart person’s safety school than a smart person’s competitive school.” Pollack believes that since Columbia was not coed, it was less selective, as it had twice as many spaces for male applicants as the other Ivies. This made it a less attractive choice for top-tier students.

In 1980, Arnold Collery, then Dean of the College, appointed a committee to look into the coed issue. The committee did some research and concluded in a report, published in April 1981, that Columbia College needed to admit women. As Robert McCaughey, Professor of History and Janet H. Robb Chair in the Social Sciences at Barnard College, put it, the report “contended that Columbia, if it was going to maintain any kind of standing within the Ivy League, better start recruiting women pretty fast.” Bolstered by this conclusion, and another within the report that Barnard College would be able to survive the change, Columbia’s faculty and trustees voted in the 1981-1982 academic year to begin accepting women.

Mark Lebowitz, (CC, ’86), a member of the last all-male class, recalls the sentiment among his fellow Columbia students that coeducation would make Columbia more selective. Many also thought that it would make the College more appealing, especially in an age when coed colleges were increasingly becoming the norm. Notwithstanding these advantages, there were many at Columbia, including Pollack, who simply believed that women should be admitted as a matter of principle.

Columbia accepted its first coed class for the fall of 1983; women comprised 45% of the class. Admitting female students immediately impacted Columbia’s selectivity, dropping its admissions rate from 40% for the class of 1986 to 31% for the class of 1987. McCaughey focuses on this particular result: “The first set of women and then on were at least as good as the typical Columbia student, so it lifted the whole. One way to look at it is that Columbia got rid of the bottom half of its class and replaced it with women who ranked with the students who were in the upper half.” Pollack, however, was more concerned with the fact that for the first time in 229 years, women could attend Columbia College. He hails the switch to coeducation as his greatest achievement as Dean. “How often does anybody get a chance to break a 200-year-old precedent and make it work?”

In going coed, Columbia leveled the playing field with other Ivies, but it remained to be seen how this decision would affect its long-time partner, Barnard College.

Balancing Barnard

Barnard College was founded in 1889 primarily in response to the fact that women could not attend Columbia College. Located directly across the street, Barnard was founded as a women’s college that would accompany Columbia and provide women with a similar caliber of education. Based on its original intent, the question arose: if Columbia went coed without including Barnard, would Barnard be able to survive as a women’s college, or would its reason for existence simply disappear? Columbia’s uncertainty about how coeducation would affect Barnard is part of the reason why it delayed this major decision for so many years.

Almost immediately, the possibility of Columbia College simply absorbing Barnard College, as Harvard College had done with Radcliffe College, was taken off the table. Barnard’s faculty voted to remain independent—they did not want to be swallowed up by Columbia. Pollack believes that “Barnard faculty did not want to teach in the Core, and that was why Barnard didn’t become the Radcliffe to Columbia.” He further contends that the Barnard faculty did not want to give up their academic trademark, the required senior thesis, for Columbia’s signature Core Curriculum. However, a different—more compelling—reason, was that Barnard faculty were employed separately from Columbia faculty, and if Barnard were to be combined with Columbia, many of them would lose their jobs altogether. This concern did not exist in the case of Harvard and Radcliffe because the two schools had always shared faculty.

According to Professor McCaughey, some Barnard students and faculty members, including himself, were “more disposed toward a merger than the institution was.” There were even some Barnard trustees in the early 1970s who were willing to accept a merger, but those trustees left the board by the early 1980s, before the coeducation question truly gained momentum. By the time of the critical vote in 1982, most of the trustees wanted Barnard to remain independent and believed that it was not in Barnard’s best interest for Columbia to become coeducational.

Still, in the early 1980s, before Columbia officially decided to admit women, alternative solutions were proposed. Barnard attempted to find an arrangement that would satisfy Columbia without it going fully coed. One of these possibilities was for Columbia to have “virtual coeducation.” This meant that it would have the same percentage of women in its classrooms as other Ivy Leagues, including Core classes (which had always been all-male), but without actually admitting women to Columbia College. However, this alternative would mean that women still could not be admitted directly to Columbia, so the coeducation issue was not really solved. Additionally, this solution would decrease the number of students enrolled in Barnard classes, since they would be busy taking Core classes at Columbia, decreasing the need for Barnard faculty and ultimately harming the school. As a result, this proposed solution did not garner much support, especially since the protection of its faculty was one of the main reasons that Barnard opposed the merger. Negotiations continued throughout the early 1980s to find an arrangement that would work for both sides of Broadway, but Barnard ran out of time: Columbia’s president, faculty, and trustees went ahead with coeducation anyway.

As expected, Barnard’s admissions suffered during the first few years after Columbia started accepting women. McCaughey theorizes that some women who previously would have gone to Barnard chose to attend Columbia instead, but after the first couple of years Barnard recovered. One possible explanation is that most women who were applying to Barnard were not deciding between Barnard and Columbia or between different Ivy League schools, but between Barnard and other women’s colleges.

Barnard effectively rebranded itself, playing up its status as a women’s college and its location in New York City, while also emphasizing its connection with Columbia. This unique marketing formula has allowed Barnard admissions to become more competitive each year. Barnard took full advantage of its affiliation with Columbia, but the cooperation between the two schools didn’t just benefit Barnard: Columbia took advantage of certain majors that were only offered at Barnard, such as dance and architecture, as well as utilizing Barnard’s help in developing its own women’s studies program.

Barnard also evolved as its own institution independent from Columbia. Qualities unique to Barnard include a strong focus on women’s and gender studies, a small and supportive community, and female empowerment. Barnard certainly took advantage of Columbia’s resources, but ultimately it thrived as a college in its own right and has survived based on its own merits.

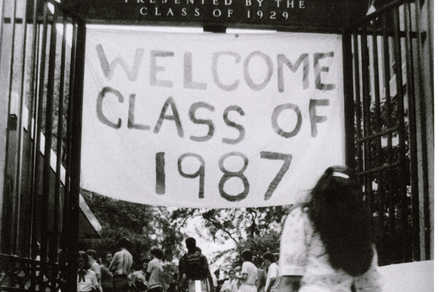

August 1983 in Morningside Heights. Photo courtesy of the Columbia University Archives.

August 1983 in Morningside Heights. Photo courtesy of the Columbia University Archives.

Women Come to Columbia

Pollack used the entrance of women to the Class of 1987 as an opportunity to renovate the dorms, feeling that they needed an upgrade if women would be living there. Additionally, under Title IX Columbia was required to provide equal opportunity for men and women’s athletics and so Pollack established the Columbia-Barnard Athletic Consortium. This enabled Barnard women to compete in the Ivy League as well as Division I sports, and it allowed Columbia to begin a competitive women’s athletics program immediately. The athletic department’s facilities were also renovated to accommodate women and give it a much-needed upgrade.

When the women first arrived at Columbia in the fall of 1983, they encountered a lot of enthusiasm surrounding coeducation. As Linda Mischel Eisner, (CC, ’87), recalls: “There was a feeling of excitement from faculty that the institution was undergoing a positive change.” There was a lot of press coverage of the first coed class, and the administration made a big deal of it at convocation.

Lee Ilan, a member of the Class of 1987, notes that the first women thought of themselves as “pioneers, doing something exciting. We knew we were bringing a different perspective to discussions, residence halls, and expectations of campus.” Lebowitz noticed this change in classroom discussions, particularly in his Literature Humanities class, where he felt that the women had a different perspective on the books than the men.

Beyond this and some minor changes in his social life, though, Lebowitz did not see much of a difference following the arrival of the first women. There were already many female undergraduates at Columbia University, including at Barnard, the School of Engineering, and General Studies, so it was not unusual to have women on campus—now there were just more of them. “I think because Columbia was coed as a university overall, upperclassmen in the College were reasonably accustomed to a coed educational environment and relationships were smooth,” says Eisner.

Selling a Coed Columbia

Although many reactions to the change were positive, not everyone was enthusiastic about Columbia admitting women. One alumnus approached Pollack saying, “You’re making it so much harder for my sons to get in [to Columbia],” to which Pollack responded, “But I’m making it infinitely easier for your daughters to get in.” Other alumni had similar complaints. Partly in order to deal with this backlash, the Columbia Office of Admissions hired a female basketball star from one of the first coed classes at Yale, Diane McKoy, who still works in the Office of Admissions today. Pollack directed alumni to her as a way of halting any criticism of coeducation. “Basically, we’d go around the country together and give talks, and I’d give a little talk, and I’d say, ‘Now Diane.’ And you could see the audience understood the game was up.” McKoy was living proof of the benefits of coeducation, and it was impossible to argue against coeducation to her face. In this way Pollack was able to quiet opposition to the change.

As Dean of the College, Pollack’s main job was to fundraise, which required selling coeducation to alumni, but this wasn’t difficult: many jumped at the chance to support coeducation at their alma mater. Pollack recalls, “When I had the opportunity to bring a person to Columbia and ask them for a scholarship, I never took them to a fancy restaurant, I never took them downtown. I insisted they come to John Jay [Dining Hall] to have lunch with me and the freshmen, and see a coed class, which didn’t exist when they went there. And I’m not exaggerating, they’d burst into tears and write a check—it was that easy. Because that was what they couldn’t imagine.”

What was once impossible to imagine is now an accepted reality. Columbia University is a unique choice for women, offering exceptional coeducational undergraduate options as well as a thriving women’s college. Pollack reflects, “We were the only one to admit to the multiplicity of lives, of women’s lives, the diversity of strategies for becoming a fully respected human being as a woman. One way is to go to a women’s college and get strength that way, the other way is to jump into a coed place, and Columbia offered both.” This model has been extremely successful, and current students now view coeducation as a fact of life at Columbia. “The real success,” Pollack concludes, “is that [coeducation] is taken for granted.”

Note:

Much of the material for this article came from interviews with Dr. Robert Pollack, Professor Robert McCaughey, Linda Mischel Eisner, Lee Ilan, and Mark Lebowitz. Additional sources used were Columbia College Today’s article on the 25th anniversary of the graduation of the first coed class, Columbia College Today’s article on 25 years of coeducation at Columbia, and a New York Times article about the commencement ceremony of the first coed class.

Pollack used the entrance of women to the Class of 1987 as an opportunity to renovate the dorms, feeling that they needed an upgrade if women would be living there. Additionally, under Title IX Columbia was required to provide equal opportunity for men and women’s athletics and so Pollack established the Columbia-Barnard Athletic Consortium. This enabled Barnard women to compete in the Ivy League as well as Division I sports, and it allowed Columbia to begin a competitive women’s athletics program immediately. The athletic department’s facilities were also renovated to accommodate women and give it a much-needed upgrade.

When the women first arrived at Columbia in the fall of 1983, they encountered a lot of enthusiasm surrounding coeducation. As Linda Mischel Eisner, (CC, ’87), recalls: “There was a feeling of excitement from faculty that the institution was undergoing a positive change.” There was a lot of press coverage of the first coed class, and the administration made a big deal of it at convocation.

Lee Ilan, a member of the Class of 1987, notes that the first women thought of themselves as “pioneers, doing something exciting. We knew we were bringing a different perspective to discussions, residence halls, and expectations of campus.” Lebowitz noticed this change in classroom discussions, particularly in his Literature Humanities class, where he felt that the women had a different perspective on the books than the men.

Beyond this and some minor changes in his social life, though, Lebowitz did not see much of a difference following the arrival of the first women. There were already many female undergraduates at Columbia University, including at Barnard, the School of Engineering, and General Studies, so it was not unusual to have women on campus—now there were just more of them. “I think because Columbia was coed as a university overall, upperclassmen in the College were reasonably accustomed to a coed educational environment and relationships were smooth,” says Eisner.

Selling a Coed Columbia

Although many reactions to the change were positive, not everyone was enthusiastic about Columbia admitting women. One alumnus approached Pollack saying, “You’re making it so much harder for my sons to get in [to Columbia],” to which Pollack responded, “But I’m making it infinitely easier for your daughters to get in.” Other alumni had similar complaints. Partly in order to deal with this backlash, the Columbia Office of Admissions hired a female basketball star from one of the first coed classes at Yale, Diane McKoy, who still works in the Office of Admissions today. Pollack directed alumni to her as a way of halting any criticism of coeducation. “Basically, we’d go around the country together and give talks, and I’d give a little talk, and I’d say, ‘Now Diane.’ And you could see the audience understood the game was up.” McKoy was living proof of the benefits of coeducation, and it was impossible to argue against coeducation to her face. In this way Pollack was able to quiet opposition to the change.

As Dean of the College, Pollack’s main job was to fundraise, which required selling coeducation to alumni, but this wasn’t difficult: many jumped at the chance to support coeducation at their alma mater. Pollack recalls, “When I had the opportunity to bring a person to Columbia and ask them for a scholarship, I never took them to a fancy restaurant, I never took them downtown. I insisted they come to John Jay [Dining Hall] to have lunch with me and the freshmen, and see a coed class, which didn’t exist when they went there. And I’m not exaggerating, they’d burst into tears and write a check—it was that easy. Because that was what they couldn’t imagine.”

What was once impossible to imagine is now an accepted reality. Columbia University is a unique choice for women, offering exceptional coeducational undergraduate options as well as a thriving women’s college. Pollack reflects, “We were the only one to admit to the multiplicity of lives, of women’s lives, the diversity of strategies for becoming a fully respected human being as a woman. One way is to go to a women’s college and get strength that way, the other way is to jump into a coed place, and Columbia offered both.” This model has been extremely successful, and current students now view coeducation as a fact of life at Columbia. “The real success,” Pollack concludes, “is that [coeducation] is taken for granted.”

Note:

Much of the material for this article came from interviews with Dr. Robert Pollack, Professor Robert McCaughey, Linda Mischel Eisner, Lee Ilan, and Mark Lebowitz. Additional sources used were Columbia College Today’s article on the 25th anniversary of the graduation of the first coed class, Columbia College Today’s article on 25 years of coeducation at Columbia, and a New York Times article about the commencement ceremony of the first coed class.

//HANNAH STANHILL is a freshman in Barnard College. She can be reached at hjs2144@barnard.edu. Photos courtesy of the Columbia University Archives.