//essays//

Spring 2020

Spring 2020

Community, Conflict, and Over-Confidence: A Criticism of Bari Weiss

Yona Benjamin

In the spring of 2006, Bari Weiss, then Editor-In-Chief of this magazine, published an article called “Lessons From the Palestine Solidarity Movement.” In this article, Weiss, now of The New York Times, uses a reflection on her experience at a student Palestinian rights conference to discuss what she saw as the key themes and issues related to the political conversation on campus around Israel and Palestine. Her main argument, as I understand it, is that while there is some validity to the claims of student activists for Palestine—the Palestinians do deserve rights—the 'aesthetic appeal' of these student activists masks their ultimately dangerous agenda. This agenda, says Weiss, consists of normalizing what she considers antisemitic Palestinian leadership (such as Hamas), hypocrisy about issues related to nationalism, and arguing that Zionism is antithetical to human rights.

In 2006, Weiss was concerned that Zionists might lose the PR battle, and that Jews might suffer accordingly. Since graduating from The Current to publications like The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, Weiss’s editorial work, which uses similar arguments, has become her calling card. She has expanded and refined her arguments, but the central claims remain the same: members of the far left, often Muslim college students and their allies, use appealing talk about justice and equality to marginalize Zionism and Zionists, advance radical and potentially hypocritical politics, and perhaps even endanger Jews. As Weiss’s (eventual) successor at The Current, I am fascinated by her career and her broad appeal in the American Jewish community.

The world, and Columbia, have changed in many ways since Weiss founded The Current, but they have also stayed the same. Weiss herself has perhaps remained the most consistent. Her writing toes the same line as it seems to have done in college, and she continues to make very similar criticisms. She ends her 2006 piece by decrying a ‘false binary’ between being a respectable liberal (today we might use the term ‘progressives,’ as criticisms of ‘liberalism’ are becoming more coherently formulated in mainstream non-conservative politics) and being a Zionist. In a 2019 interview with Joe Rogan, Weiss offered a very similar argument, claiming that opposition to Israel is unthinkingly tacked onto the list of standard progressive opinions (she notes “criminal justice reform and any number of things'' as an example.) In both statements, made thirteen years apart, Weiss’s point is the same: it is unfair that support of Israel is considered unacceptable for progressives. Further, I feel as if in some of her more recent writings, she has become a proponent of a sort of siege mentality for the American Jewish community, indicative of how she now takes on the mantle of public Jewish intellectual, yet with the same concerns as when she began her career. I think Weiss is diagnostic of the mentality that many American Jews have about the way their Zionism relates to broader politics. Therefore, an examination and criticism of Weiss’s views, especially their unflinching nature, will serve as an apt starting ground for probing questions about the nature of the American Zionists’ commitments and attitudes.

Weiss argues that it does not make sense for progressives to oppose Zionism. The argument can be formulated in many ways, but Weiss describes Zionism as “the marriage of the ancient Jewish yearning to return to the Holy Land told with the dream of modern self-determination.” For her, Zionism is the consummation of a minority people’s search for fulfillment in modernity. Hence, progressives should applaud Israel’s existence as a moment of minority liberation, and failure to do so is a result of either ignorance or antisemitic two-facedness. Weiss at no point in any of her editorials stops to consider or engage with the nuances of her opponents’ arguments. Weiss is correct that Jews around the world have suffered and continue to suffer at times due to their Jewish identity. But this is not the only relevant factor in considering the Zionist question. Zionism’s logic has been and always will be that the self-determination of Jewish people is more important a goal to secure than the rights and recognition of pre-existing Arab populations in ‘The Holy Land.’ No matter how progressive a Zionist one is, the emancipation of Arabs has always come second (at least in sequence if not in priority) to that of the Jews.

Many on the left object to this in particular: not to the empowerment of the Jews, but the wholesale relegation of this other group. A two-state solution fails to adequately address this disenfranchisement, as Arabs within what would become the Zionist state would also be disenfranchised in their own homes, as the state they lived in would merely tolerate them, rather than exist for them in the way it would for its Jewish citizens. Zionism’s development is also a chapter in the ongoing legislation of European colonialism in which European populations are given privilege of place over others. From a critical perspective, that the Jews suffered in Europe and elsewhere is not a compelling justification for Zionism, just as the mistreatment of Native Americans is not justified by the fact that many Jamestown colonists were the downtrodden outcasts of British society. Weiss fails to engage with these points across any of her writings, and so, in each of her pieces, maintains the view that it is madness for progressives not to champion her cause. Her narrow approach across her works fails to acknowledge that these ‘progressives’ may in fact have reasons for opposing Zionism which are informed by moral calculus and which are potentially consistent with their broader views. While Weiss could very well be correct in saying that Zionism is a just cause (I happen to think it is not, but I am at least as fallible as her) Weiss’ arguments ring empty thanks to her lack of acknowledgement of thoughtful, nuanced counter-arguments.

I believe that this attitude is diagnostic of the mindset which many American Jews inhabit. There is an a priori assumption among many American Jews that this sort of blind support of Israel, which fails to engage with opposing narratives, is an important part of their Jewish identity. However, many of us arrive at this view without serious engagement, or even acknowledgement of opposing voices. Many people in the American Jewish community, just as Weiss does, write off opponents of Zionism without taking them seriously. This is a serious blunder, and prevents people from engaging critically in a broad range of important perspectives. Weiss, as a thought leader of sorts, ought to be thinking along different lines. Indeed, Judith Butler, in a review of Weiss’ book, calls upon Weiss to be braver when she calls for “More courage, Bari Weiss!”

As a result of these attitudes, Jewish opposition to Zionism becomes silenced, or perhaps is unable to ever be truly heard. This is not merely derivative of the previous issues discussed, but is in fact its own beast. This second issue is connected with Weiss’ narrow notion of what it means to be a good Jew. Again, Weiss is emblematic of the view that is held by many American Jews, one which I would argue is unfair, inaccurate, and ultimately self-destructive.

I see Weiss as conceiving of Jewish identity as oppositional, confrontational, and inflexible. Her views are best distilled in a recent op-ed entitled “To Fight Anti-Semitism, Be a Proud Jew.” Weiss argues that there is a continuous distinction in Jewish history between Jews who choose to accept the challenge of freedom and autonomy, and those who choose to live as slaves. For Weiss, this is best demonstrated by the traditional idea that while many Jews chose to be liberated from slavery in Ancient Egypt, a majority chose to remain slaves, too afraid of the freedom offered to them. Weiss claims that we can see this distinction playing itself out across Jewish history, from the Maccabean revolt, through the Stalinist purges, and even today, in the American community discourse around antisemitism and Zionism. Weiss describes the first paradigm, saying: "Safety for Jews comes by accommodating ourselves to the demands of our surrounding society. If we can just show we are perfect Greeks, patriotic Germans, and so on, then they’d love us. (Or at least not kill us.)" The second group, she claims, belong in the realm of "the Maccabees to the Zionists, that urged us to be our fullest, freest selves — even if doing so made us deeply unpopular or despised."

This distinction is a shocking one for many reasons, but especially because it seems to suggest that the only alternative to Zionism as Weiss understands it is a complete debasement of Jewish pride and culture. Indeed, in the same article, Weiss discusses Stalinist Jews as the counterbalance to proud Zionism, as if Jews (like me) who are critical of Zionism, are akin to apologists for Gulags and mass-starvation. However, what I consider most troubling, especially when we consider that Weiss may be indicative of many American Jews’ thinking, is the idea that proud Judaism for Weiss might entail the rejection of coexistence, collaboration, and interdependence with broader communities.

Weiss makes it clear that she is proud of the caring relationships that Jews have with their neighbors, citing the response of her hometown community in Pittsburgh to the tragic shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in October 2018. However, I worry that if people take Weiss’s other work seriously, considering her inability to acknowledge opposing views, those types of relationships will become harder to foster. It would seem that Weiss would not be grateful to her neighbors if they were anti-Zionists, even if their anti-Zionism was informed by the same values which urged them to support their Jewish fellows in the wake of a bigoted attack. Due to the stiff-necked and oppositional stance Weiss takes in defending her Zionism, paired with the fact that she seems uninterested in engaging with her intellectual opponents, the idea that her thinking can inform a culture "capable of lighting a fire in every Jewish soul — and in the souls of everyone who throws in his or her lot with ours” seems rather far-fetched. Weiss will presumably continue to remain a prominent Jewish public intellectual, and so those of us with criticism of her work must continue to vocally state our case, in doing so, we ask important questions about the direction, values, and mindset of our broader community. I know that as my tenure as Editor-in-Chief at this magazine comes to a close, there is still a platform at Columbia for young Jews, and their non-Jewish peers, to think bravely, closely, and with a commitment to a better community and world.

//Yona Benjamin is a senior at in the GS/JTS Joint Program and serves as Editor-in-Chief of The Current. He can be reached at [email protected].

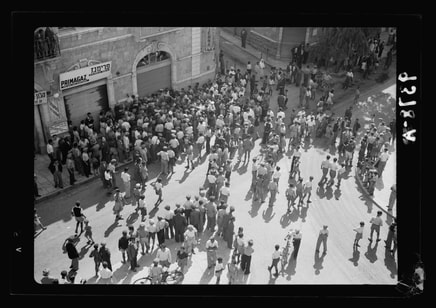

Image Jewish protest demonstrations against Palestine White Paper, May 18, 1939. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.