//essays//

Fall 2018

No Man is an Island, But This Block is

Dassi Karp

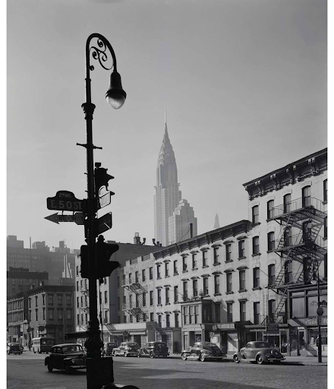

The Type F Bishop’s Crook lamppost was once a common sight throughout Manhattan. It was so pervasive that, at the turn of the twentieth century, it became a distinguished symbol of New York City. (1) Its graceful arching head and curliqued garland ornamentation has been largely replaced on the Upper West Side with more modern and utilitarian poles in the last fifty years.

The residents of West 95th Street between Central Park and Columbus, fanatical about the history of their small part of the city, remembered the older lampposts. They missed their elegance, and organized a campaign for replicas of the historic lampposts to once again line their street. After months of pestering the bureaucracy of New York about historical designations, money collection, and the general haranguing that tends to define group efforts, members of the West 95th Street Block Association gathered in late May of 2017 to celebrate the installation of their new lampposts.

For many of its residents, New York City feels vast and cold. People live there briefly and make little impact on the history of such a large and complex city. New York is a place where hundreds of people live within a few steps of each other, but might never interact. A place where people can move into and out of an apartment without once attracting the attention of their neighbors. A place where people are unlikely to remember the name of a shop on their street that closed just a few weeks ago, much less the type of lampposts that had graced their streets in what could be considered the city’s ancient history.

The individuals who reside on West 95th Street live in a different New York City. They have worked to form a community with a small town feel, not that of a sprawling metropolis. This is a community that bands together not just to replace lampposts, but also to celebrate life cycle events and holidays. The homeowners on the block range from retirees to families with young children. Like any New York City block, the residents of West 95th Street have little that unite them; their ages and backgrounds, interests and professions all vary dramatically. But their drive to build community and their passion about their place in New York’s history has for decades set them apart from every other city block. As its residents are quick to point out, West 95th Street has its own story. It is that of one city block moving closer together as the city around it continues to spread apart.

The block, and the area that surrounds it, did not start out as a communal venture, or even as a part of New York City. The area that became the Upper West Side remained undeveloped until considerably after the Civil War. Instead of the densely populated streets that characterized the lower part of the is- land, the area above Canal Street consisted of “open woodland,” featuring farms and homesteads scattered about rocky fields. (2) As a current resident of the area put it, it was a “pristine, virgin territory...before these houses, it was sheep and goats.”

Development in what was then called “Bloomingdale Village” began with the introduction of a trolley service in 1878 and the Ninth Avenue El, an ambitiously planned elevated railway, in 1879. Shops and tenement buildings were erected and single-family row houses were built for the more prosperous families on the streets. (3) Those who moved into these homes were not a monolithic bunch; these early residents included a notorious police official, a real estate mogul from Minnesota, and a family who operated a military supply business. They were not among the extremely wealthy of the city, but they were certainly well-off, living in degrees of luxury. (4)

In the early decades of the twentieth century, this upper Manhattan neighborhood grew, and West 95th Street found itself at the center. Now framed on one side by the expanse of Central Park, and on the other by the shops on Columbus Avenue, residents were able to enjoy some of the city’s best features. Large Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and Catholic churches loomed on nearby blocks. Columbia University’s new Morningside Heights campus opened in 1896, expanding the prestige and the physical footprint of the West Side northward. (5)

New York’s population was exploding, and styles of living had to adapt to accommodate it. Through the 1920s, the Upper West Side engaged in a continuous process of demolition and reconstruction. This boom had to end eventually, and when the Great Depression hit, West 95th Street was no exception. Many of the homeowners were forced to sell their homes, or subdivide them into rented apartments. Some of the brownstones remained single-family units, but even these fell into disrepair. This period of financial decline, which lasted well into the 1970s, marked a shift that brought in a new generation of owners. It was this group that planted the seeds of the community that exists today.

This new group of residents consolidated the block’s informal connections into the “West 95th Street Residents Association,” a formal organization that included both owners and their tenants. This organization continued the process of combating a range of problems facing their block. Some as simple as when, in the early 1970s, this group set out to adorn their neighborhood with flowers, both on the sides of the streets and in apartment windows.

This unity began to extend beyond a shared interest in their street’s aesthetics. Among with the rest of New York City, the Upper West Side in the 1970’s and 80’s became increasingly concerned with crime, especially the proliferation of break-ins, muggings, and drug-sales. As the block began to see itself as part of a more distinct community, they developed their own response systems to supplement those of the city. The block president at the time initiated a “whistle program,” in which whistles were distributed across the community. If anyone was in trouble or sighted something suspicious, would begin to blow their whistle, and neighbors who heard these calls would join in. This cacophony often scared criminals away, and was an early example of the inherent potential in the block’s unity.

As time passed, the block’s connections continued to proliferate. The older children in these families babysat for each other and the younger ones trick-or-treated together. Their parents shared parenting suggestions, passed family recipes, and brainstormed new events. On several nights each summer, the block closed for a volleyball game. They held block fairs and organized block-wide Christmas caroling. They successfully created a tight-knit community within New York City.

This is not to say that West 95th Street was always in agreement in handling larger issues facing the city. Residents recounted instances of disagreement on topics such as low-income housing and the creation of homeless shelters. These disagreements sometimes even extended to details in the structures of buildings on the block itself. But as the years progressed, even the public discussion of these disagreements began to disappear. The residents’ formal involvement in and commitment to community began to wane, and the block’s infrastructure was mostly maintained by its older and most committed residents.

What has stood the test of time, though, is that there are people who care enough about each other and their shared history to talk about it—people of varying ages and radically different backgrounds. People who have nothing to do with each other aside from a common place of residence and the will to create community.

The residents of West 95th Street between Central Park and Columbus, fanatical about the history of their small part of the city, remembered the older lampposts. They missed their elegance, and organized a campaign for replicas of the historic lampposts to once again line their street. After months of pestering the bureaucracy of New York about historical designations, money collection, and the general haranguing that tends to define group efforts, members of the West 95th Street Block Association gathered in late May of 2017 to celebrate the installation of their new lampposts.

For many of its residents, New York City feels vast and cold. People live there briefly and make little impact on the history of such a large and complex city. New York is a place where hundreds of people live within a few steps of each other, but might never interact. A place where people can move into and out of an apartment without once attracting the attention of their neighbors. A place where people are unlikely to remember the name of a shop on their street that closed just a few weeks ago, much less the type of lampposts that had graced their streets in what could be considered the city’s ancient history.

The individuals who reside on West 95th Street live in a different New York City. They have worked to form a community with a small town feel, not that of a sprawling metropolis. This is a community that bands together not just to replace lampposts, but also to celebrate life cycle events and holidays. The homeowners on the block range from retirees to families with young children. Like any New York City block, the residents of West 95th Street have little that unite them; their ages and backgrounds, interests and professions all vary dramatically. But their drive to build community and their passion about their place in New York’s history has for decades set them apart from every other city block. As its residents are quick to point out, West 95th Street has its own story. It is that of one city block moving closer together as the city around it continues to spread apart.

The block, and the area that surrounds it, did not start out as a communal venture, or even as a part of New York City. The area that became the Upper West Side remained undeveloped until considerably after the Civil War. Instead of the densely populated streets that characterized the lower part of the is- land, the area above Canal Street consisted of “open woodland,” featuring farms and homesteads scattered about rocky fields. (2) As a current resident of the area put it, it was a “pristine, virgin territory...before these houses, it was sheep and goats.”

Development in what was then called “Bloomingdale Village” began with the introduction of a trolley service in 1878 and the Ninth Avenue El, an ambitiously planned elevated railway, in 1879. Shops and tenement buildings were erected and single-family row houses were built for the more prosperous families on the streets. (3) Those who moved into these homes were not a monolithic bunch; these early residents included a notorious police official, a real estate mogul from Minnesota, and a family who operated a military supply business. They were not among the extremely wealthy of the city, but they were certainly well-off, living in degrees of luxury. (4)

In the early decades of the twentieth century, this upper Manhattan neighborhood grew, and West 95th Street found itself at the center. Now framed on one side by the expanse of Central Park, and on the other by the shops on Columbus Avenue, residents were able to enjoy some of the city’s best features. Large Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and Catholic churches loomed on nearby blocks. Columbia University’s new Morningside Heights campus opened in 1896, expanding the prestige and the physical footprint of the West Side northward. (5)

New York’s population was exploding, and styles of living had to adapt to accommodate it. Through the 1920s, the Upper West Side engaged in a continuous process of demolition and reconstruction. This boom had to end eventually, and when the Great Depression hit, West 95th Street was no exception. Many of the homeowners were forced to sell their homes, or subdivide them into rented apartments. Some of the brownstones remained single-family units, but even these fell into disrepair. This period of financial decline, which lasted well into the 1970s, marked a shift that brought in a new generation of owners. It was this group that planted the seeds of the community that exists today.

This new group of residents consolidated the block’s informal connections into the “West 95th Street Residents Association,” a formal organization that included both owners and their tenants. This organization continued the process of combating a range of problems facing their block. Some as simple as when, in the early 1970s, this group set out to adorn their neighborhood with flowers, both on the sides of the streets and in apartment windows.

This unity began to extend beyond a shared interest in their street’s aesthetics. Among with the rest of New York City, the Upper West Side in the 1970’s and 80’s became increasingly concerned with crime, especially the proliferation of break-ins, muggings, and drug-sales. As the block began to see itself as part of a more distinct community, they developed their own response systems to supplement those of the city. The block president at the time initiated a “whistle program,” in which whistles were distributed across the community. If anyone was in trouble or sighted something suspicious, would begin to blow their whistle, and neighbors who heard these calls would join in. This cacophony often scared criminals away, and was an early example of the inherent potential in the block’s unity.

As time passed, the block’s connections continued to proliferate. The older children in these families babysat for each other and the younger ones trick-or-treated together. Their parents shared parenting suggestions, passed family recipes, and brainstormed new events. On several nights each summer, the block closed for a volleyball game. They held block fairs and organized block-wide Christmas caroling. They successfully created a tight-knit community within New York City.

This is not to say that West 95th Street was always in agreement in handling larger issues facing the city. Residents recounted instances of disagreement on topics such as low-income housing and the creation of homeless shelters. These disagreements sometimes even extended to details in the structures of buildings on the block itself. But as the years progressed, even the public discussion of these disagreements began to disappear. The residents’ formal involvement in and commitment to community began to wane, and the block’s infrastructure was mostly maintained by its older and most committed residents.

What has stood the test of time, though, is that there are people who care enough about each other and their shared history to talk about it—people of varying ages and radically different backgrounds. People who have nothing to do with each other aside from a common place of residence and the will to create community.

1 http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/1961.pdf

2 Gloria Deák, Picturing New York (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

3 John Rousmaniere, “Upper West Side,” in Kenneth T. Jackson, ed., The Encyclopedia of New York City, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

4 Sheila C. Gordon, Lamps, Lives, and Lore: A Brief History of One Manhattan Block and its Community, Unpublished manuscript (New York: 2018), 12.

5 Robert McCaughey, Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University in the City of New York, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 164.

2 Gloria Deák, Picturing New York (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

3 John Rousmaniere, “Upper West Side,” in Kenneth T. Jackson, ed., The Encyclopedia of New York City, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

4 Sheila C. Gordon, Lamps, Lives, and Lore: A Brief History of One Manhattan Block and its Community, Unpublished manuscript (New York: 2018), 12.

5 Robert McCaughey, Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University in the City of New York, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 164.

//DASSI KARP is a senior in Barnard College. She can be reached at hlk2125@barnard.edu.

Photo courtesy of: http://www.21steditions.com/todd-webb-entries/.

Photo courtesy of: http://www.21steditions.com/todd-webb-entries/.