//features//

Spring 2018

Queering Her Yiddish World

An Interview with Professor Irena Klepfisz

Julia Crain

The expulsion of three women from the 2017 Dyke March in Chicago for carrying Jewish pride flags epitomizes the sort of hostility that Irena Klepfisz faced for coming out as a lesbian within the Yiddish world of 1970s New York. Neither the lesbian activist circles she took part in during the 1970s and ‘80s nor the Bundist community in which she was raised ever recognized or accepted her experiences in full. Nevertheless, Klepfisz fought—and continues to fight—for equal rights and self-representation. Her resilience and unending pursuit of justice are, perhaps, a byproduct of her upbringing. Born in occupied Poland to Rose Perczykow Klepfisz and Michał Klepfisz—a leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising—she and her mother survived the Holocaust by disguising themselves as non-Jewish Poles and fleeing the country in the midst of the 1944 Polish Uprising of Warsaw. After moving to America, Klepfisz became active in Leftist Jewish communities and launched herself in the burgeoning movement for lesbian and women’s rights, all the while never straying from her Bundist values and commitment to Yiddish life and culture.

Julia Crain sat down with Irena Klepfisz, who is an Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Barnard College, to speak about her life and career as a Yiddishist, lesbian activist, and poet. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Julia Crain: What was life like for your family in Poland before the war started?

Irena Klepfisz: I wasn’t born before the war started. My parents were secular Jews in Warsaw. My father came from a socialist background, the Jewish Labor Bund, and my mother fell into that after she married him. He was finishing a degree in engineering, but she didn’t have much of an education. She came from a rather large family, and her father died when she was twelve. At that point, she had to go to work. She educated herself. She loved to read… I think I got my love of literature from her. My parents got married and had their own plans, and then everything got off course.

JC: You were born during the war. What year was that?

IK: 1941.

JC: What was life like for you during and after the war?

IK: Well, I don’t remember it, so I can only tell you what I’ve been told. My father was involved in organizing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. He went in and out of the Ghetto fairly regularly, as other members of the Underground did, and he took my mother and me out. I was placed, six months before the Uprising (in April 1943), in a Catholic orphanage on what was called the Aryan side, the part outside of the Ghetto. My mother had false papers that said she was Catholic, and she worked as a maid. [My father] was killed on the second day of the Uprising, and the Ghetto was demolished. A year later was the Polish Uprising of Warsaw. At that point, my mother snatched me and got out of the city until the end of the War. She then connected with members of the Jewish Labor Bund, and we went to Łódź. We stayed there for a year. In 1946, we went to Sweden, and we stayed there for three years. I learned Swedish, and I learned to ski and skate and ride bicycles—all the great things. I went to first and second grade in Sweden, and then we came here.

From there, it’s quite undramatic. I lived in the Bronx through college. I went to City College, and I went to graduate school at the University of Chicago for six years. Then, I came back and started living in Brooklyn. I came out and was very active in the Lesbian Feminist Movement and all kinds of publishing ventures… I also became involved in the Jewish Women’s Movement.

JC: To take a few steps back to your childhood, At what point did you learn to speak Yiddish?

IK: I don’t quite know the answer to that. I certainly didn’t hear it in the orphanage, and I didn’t hear it for the rest of the war. When we started living with other people who had survived in Łódź, I started hearing a lot of Yiddish. My mother, though, continued to speak to me in Polish. Then we moved to Sweden, and a lot of people there spoke Polish and Yiddish. When we got to the States, there were Yiddish schools. My mother sent me to an afternoon shula [Yiddish school]. That was the first time I was asked to speak and to write and to read. I didn’t even know the alef beis until I went there. I did a postdoc in Yiddish in the late/mid ‘70s, and I taught it for a while. Then I got interested in translating specifically women’s writers. Even now, I am not a fluent speaker in Yiddish. I am not that comfortable. I’m around people who speak Yiddish all the time, so obviously, I understand it, but it’s never been my daily language.

JC: What was your neighborhood like when you first moved to America, and what role did Yiddish culture play in the neighborhood?

IK: I was very lucky. We moved to the Amalgamated up in the Bronx, which was a cooperative with very low rents. People would pay around $10 per room as a down payment, and they didn’t own the apartment. It was established by union people, the ILGWU (International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union), and you had to belong to a union to live there. The first year, we shared an apartment with another person, which was a nightmare. It was a one bedroom apartment, and she was in the bedroom. My mother and I were in the living room. She was always sewing at home… it was really a mess.

It was a very vibrant, very engaged community. There were people from the Jewish Labor Bund who had come before the War, and there were a lot of survivors and socialists. As I mentioned, I went to the Yiddish shula, which was an afternoon school five days a week. The famous writer Chaim Grade lived in the Amalgamated. Everyone read the Yiddish Daily Forward. The first conversations I heard that were intellectual and political were in Yiddish. The Yiddish speakers talked endlessly about what life was like before the war. To me, it was a very wonderful environment. I admired a lot of the people. But I also got very mixed messages. They wanted their children to be very yiddishe and so on, and at the same time, they wanted their children to succeed in the outside world. There were mixed signals about what to prioritize. We were all first generation college kids. I was the first person in the whole group who got a PhD, but I was older than most of the kids because I was from the war, and most of the kids were born after the war.

I look back on it all with an enormous amount of affection and commitment. I never rebelled politically; I just had to figure out how it translated.

JC: What role did Jewish ritual play in that community?

IK: Almost none… well some. The Bundists and socialists didn’t totally cut themselves off. We celebrated what we considered political holidays, such as Hanukkah, Purim, and Pesach. Those were major holidays for us, but we never did Yom Kippur or Rosh Hashanah, and the first time I stepped into a shul I was in my forties. We also commemorated the Holocaust on April 19th, the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. That was a holiday. I had never heard of Tisha B’av, for example, until I went away to a Jewish camp that used Tisha B’av to talk about the Holocaust. I only really became familiar with religious aspects of Judaism when I became active in the Women’s Movement, and I was forced into it. I was working with women who were observant, and I wanted to be sensitive, so I started learning. A friend and I did a feminist Haggadah. I have a whole bunch of xeroxed Haggadahs with all kinds of goddesses on them.

JC: In your essay “Secular Jewish Identity: Yiddishkayt in America,” you wrote that “the absorption of feminism in to my politics, the recognition of gay oppression represented a major shift in my perspective.” What influenced your feminism? How did you become aware of discrimination toward LGBTQ people?

IK: I became aware of it when I realized that maybe I was gay; nothing does it better than that. I feel I was very lucky, though, because when I came out, which was in 1973, New York was just hopping. It was exploding. It was after Stonewall. Lesbians started getting organized. I belonged to a group of lesbian writers. There were four of us who decided to start Conditions magazine, for example, and before that we had a group called Di Vilde Chayas [the wild animals], which was a group that had Adrienne Rich, Melanie Kay Kantrowitz, Gloria Greenfield, and Evelyn Beck, who did Nice Jewish Girls. Women looked at my background, and they thought, ‘Oh, she’s authentic. She’s the real deal… from Europe, from the War. She’s a child survivor. Wow.’ I just got sucked in.

I was frightened—I mean I got pushback, even in the community in the Bronx; nobody was happy. My mother was not happy. It was difficult, and I did not like being public. It was many many years ago, and I’ve gotten much more comfortable speaking about myself publicly, but at the time, it was very hard.

The Jewish Labor Bund was a non-Zionist organization, so I barely thought about Israel. But if you’re going to be involved with the Left, you’ve got to start thinking about Israel. Melanie and I became very committed to supporting the Women in Black in ‘87. I formed a group here, the Jewish Women’s Committee to End the Occupation (JWCEO) with Clare Kinberg and Grace Paley. We wanted to be identified as Jews protesting.

JC: You write about feeling trapped between two worlds: the Yiddish world and the feminist/lesbian worlds. In what way were these worlds separate? What were some of the barriers to integrating these communities?

IK: When I first came out in the ‘70s, I came out to myself and to friends, but I couldn’t come out in the Jewish world. When I published my first book, I had lesbian poems in there. Some people got it, and some people didn’t. There were people who only wanted to look at my Holocaust poetry. They pretended like there was nothing else. On the other hand, there were lots of lesbians who were just interested in my lesbian poems and could care less about the Holocaust ones. It was very difficult for me to give readings because I never had an integrated audience. It was only many years later, in the ‘90s, when I became better known and would be invited to campuses, for example, that my readings would be co-sponsored by an English department, a women’s center, and an LGBT committee or group. When I did these things, people would always say, ‘Gee, we’ve never had such a mixed audience before.’ In the ‘70s… this was still too raw. Some of it was quite ugly, and it was very disappointing for me to see the community that I had come out of be so bigoted.

JC: What were some of the hostilities that you observed?

IK: First of all, I knew I had to be quiet in order to keep jobs. It was just considered unseemly to be in a relationship with a woman. I certainly couldn’t bring my partner anywhere. I couldn’t talk about my partner. I couldn’t talk about my life. I’m not sure I wanted to talk that much, but I couldn’t be open or casually refer to things. It was very unpleasant and enraging. It’s changed, at least it’s certainly changed here, in New York. The Yiddish world, I sometimes think, is more gay than it is straight at this point.

JC: How did you reconcile the divisions you felt between these worlds?

IK: I didn’t. In a sense you sort of live with that split because it’s not in your control. It’s hard to describe, but you know what the boundaries are without anybody ever saying anything. You’re sort of one person at one moment and another person at another moment. I suppose the only time that you’re ever really complete is when you’re by yourself or in an environment in which you’re not hiding. In the gay community, I was not hiding my Jewishness. Not everybody was interested in my Yiddish work, but nobody was hostile to it. But in the Jewish world, I had to be shut down in certain ways.

JC: What motivated you to found the magazine Conditions, and what was its mission?

IK: The subtitle, which took us probably three months to come up with, was “a feminist magazine of writing by women with a particular emphasis on writing by lesbians.” We wanted to keep it open, but we did want to say there was this emphasis. The four of us were dykes, and our mission was really to publish writing. We had no place to publish, and that was really a problem.

JC: What were some of the biggest challenges in publishing the magazine?

IK: We didn't have money. And it was challenging working with the collective. We were all enthusiastic when we began, but we lived very different lives and didn’t know each other that well. It was a difficult collaboration because we had to work by consensus.

But it was ultimately great because it was a very active period and we cracked it, in the sense that we had newspapers. We had magazines. We had places not only to publish, but also to write reviews and spread the word. There were wonderful presses. It was just great.

JC: In your writing, you weave together English and Yiddish words, sometimes translating the Yiddish words and phrases, and other times leaving them untranslated. What is your intention behind these plays between languages?

IK: Because of where I grew up, I feel very attached to a society and a period that I didn’t live in: inter-war Poland (1918–1939), which is when the Jewish Labor Bund was very active. I always felt sad that I was never able to take part in that world. I think my writing was partly an attempt to bridge that gap. I felt that Yiddish was a really important part of my life, even though I wasn’t necessarily speaking it. Even my politics were fixed in Yiddish. So I started playing with it.

JC: What is it like for you to go back to Poland?

IK: I’ve been there maybe five times. My visits started in ‘83, when I went with my mother, which was her only time going back. It was the 40th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Since then, I’ve been back, and it’s always the same. I go to the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, see a couple of people from my mother’s generation, and that’s about it. This past time, I stayed with these people, who I didn’t know very well, for a month. I traveled to five cities, and I got to know a lot of their friends, Jewish and non-Jewish. A lot of them are progressives and are in opposition to the horrible current government. I probably could get in trouble for saying that; you’re not supposed to denigrate Poland. It was a very interesting trip for me because it was the first time I really dealt with the present in Poland. It’s always been about the past. From that point of view, it was a really wonderful trip, and I’m hoping to go back.

JC: You write that you have always identified as a secular Jew. What does that mean to you?

IK: I feel connected to Jewish history. I feel a part of the Jewish community, in all of its variety. As a Jew, my fate is bound up with other Jews. That could be Hasidim, Sephardim...people who are very different from me. In addition to that sense of bond and commitment, I also feel an obligation to contribute to Jewish culture, and that could take different forms. That could be my own writing, or it could be translations from Yiddish, so that people who don’t speak Yiddish can connect with Ashkenazi tradition. I don’t want Yiddish to disappear because nobody can read it. I also spend a lot of time on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I feel very much that it’s a part of me, in a way; I can’t totally distance myself from it, but I’m deeply disturbed by what’s happened there. I recognize the existence of religious texts, but I don’t necessarily believe them. I appreciate some of them from a literary or historical perspective, and I understand that they’re part of my history as a Jew, but I’m not moved by synagogue. I’m not even sentimental about it.

JC: You have been critical of the Yiddish world’s “refusal to honor Jewish difference,” and you call for greater inclusivity in the Yiddish world. What does that look like? What do you envision as an ideal Jewish community?

IK: We’re very Ashkenazi-centric. I thought about doing a course on the Jewish mother, but I decided not to do it. Practically all of the stuff I found was this Yiddish, Ashkenazi stuff. I thought, ‘Well, what are these other Jewish mothers doing?’ One of the faults of the background that I came from was the thought that they were the Jews. They didn’t really think about the Middle East or other Jews, and if they did, they probably had snotty attitudes toward them. That they were Europeans, and they were superior. There’s got to be a greater knowledge of diversity in Jewish life.

In the Women’s Movement, when we started having women’s seders, we did everything from scratch, and everyone was really happy with that. We’d come together—some of us were religious and some of us weren’t—and have this seder. We’d have these goddesses mimeographed onto Haggadahs and sit on the floor on cushions. It was potluck, so we’d have incredible food. That’s the kind of thing I like. I understand the desire to do the familiar, but there’s another kind of wonderful experience that comes from doing something not so familiar, something that is new and interesting.

I don’t think there is an ideal community—there are different kinds, and it shifts. One of the things we make a mistake about is that we want things to be static. You have to recognize when it’s become confining or rigid or prescriptive. You know, people always forget, Hasidim were considered rebels only 250 years ago. They were excommunicated! Everyone thinks they were around, walking in the desert in Palestine. They weren’t! They don’t realize that it’s much more dynamic. That gives me hope, that things change.

JC: What would you identify as the greatest threats to the preservation and growth of Yiddish culture?

IK: I think there’s a strand of people who say you have to speak Yiddish, and you have to speak it correctly. I don’t want the movement to become elitist. It used to be that Hebrew was the loshon ha-kodesh [holy language]. I don’t want Yiddish to become a holy language. I want it to be of the people, which is the way that it always was. I think that’s something to guard against.

JC: Looking at your 21-year-old self, you wrote “I realize now that I simply did not know how to be an active Jew in the world.” How can one best be “an active Jew in the world” today, in 2018?

IK: I’m not sure I can totally answer that because I don’t feel that in touch with what’s going on. I’m part of an older generation. I think the way to become active as a Jew is to become active, period.

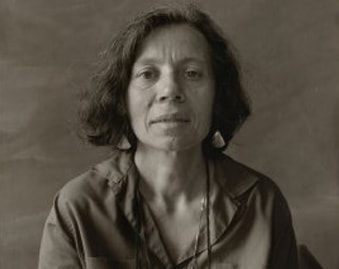

*photo by Robert Giard © Estate of Robert Giard

Julia Crain sat down with Irena Klepfisz, who is an Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Barnard College, to speak about her life and career as a Yiddishist, lesbian activist, and poet. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Julia Crain: What was life like for your family in Poland before the war started?

Irena Klepfisz: I wasn’t born before the war started. My parents were secular Jews in Warsaw. My father came from a socialist background, the Jewish Labor Bund, and my mother fell into that after she married him. He was finishing a degree in engineering, but she didn’t have much of an education. She came from a rather large family, and her father died when she was twelve. At that point, she had to go to work. She educated herself. She loved to read… I think I got my love of literature from her. My parents got married and had their own plans, and then everything got off course.

JC: You were born during the war. What year was that?

IK: 1941.

JC: What was life like for you during and after the war?

IK: Well, I don’t remember it, so I can only tell you what I’ve been told. My father was involved in organizing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. He went in and out of the Ghetto fairly regularly, as other members of the Underground did, and he took my mother and me out. I was placed, six months before the Uprising (in April 1943), in a Catholic orphanage on what was called the Aryan side, the part outside of the Ghetto. My mother had false papers that said she was Catholic, and she worked as a maid. [My father] was killed on the second day of the Uprising, and the Ghetto was demolished. A year later was the Polish Uprising of Warsaw. At that point, my mother snatched me and got out of the city until the end of the War. She then connected with members of the Jewish Labor Bund, and we went to Łódź. We stayed there for a year. In 1946, we went to Sweden, and we stayed there for three years. I learned Swedish, and I learned to ski and skate and ride bicycles—all the great things. I went to first and second grade in Sweden, and then we came here.

From there, it’s quite undramatic. I lived in the Bronx through college. I went to City College, and I went to graduate school at the University of Chicago for six years. Then, I came back and started living in Brooklyn. I came out and was very active in the Lesbian Feminist Movement and all kinds of publishing ventures… I also became involved in the Jewish Women’s Movement.

JC: To take a few steps back to your childhood, At what point did you learn to speak Yiddish?

IK: I don’t quite know the answer to that. I certainly didn’t hear it in the orphanage, and I didn’t hear it for the rest of the war. When we started living with other people who had survived in Łódź, I started hearing a lot of Yiddish. My mother, though, continued to speak to me in Polish. Then we moved to Sweden, and a lot of people there spoke Polish and Yiddish. When we got to the States, there were Yiddish schools. My mother sent me to an afternoon shula [Yiddish school]. That was the first time I was asked to speak and to write and to read. I didn’t even know the alef beis until I went there. I did a postdoc in Yiddish in the late/mid ‘70s, and I taught it for a while. Then I got interested in translating specifically women’s writers. Even now, I am not a fluent speaker in Yiddish. I am not that comfortable. I’m around people who speak Yiddish all the time, so obviously, I understand it, but it’s never been my daily language.

JC: What was your neighborhood like when you first moved to America, and what role did Yiddish culture play in the neighborhood?

IK: I was very lucky. We moved to the Amalgamated up in the Bronx, which was a cooperative with very low rents. People would pay around $10 per room as a down payment, and they didn’t own the apartment. It was established by union people, the ILGWU (International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union), and you had to belong to a union to live there. The first year, we shared an apartment with another person, which was a nightmare. It was a one bedroom apartment, and she was in the bedroom. My mother and I were in the living room. She was always sewing at home… it was really a mess.

It was a very vibrant, very engaged community. There were people from the Jewish Labor Bund who had come before the War, and there were a lot of survivors and socialists. As I mentioned, I went to the Yiddish shula, which was an afternoon school five days a week. The famous writer Chaim Grade lived in the Amalgamated. Everyone read the Yiddish Daily Forward. The first conversations I heard that were intellectual and political were in Yiddish. The Yiddish speakers talked endlessly about what life was like before the war. To me, it was a very wonderful environment. I admired a lot of the people. But I also got very mixed messages. They wanted their children to be very yiddishe and so on, and at the same time, they wanted their children to succeed in the outside world. There were mixed signals about what to prioritize. We were all first generation college kids. I was the first person in the whole group who got a PhD, but I was older than most of the kids because I was from the war, and most of the kids were born after the war.

I look back on it all with an enormous amount of affection and commitment. I never rebelled politically; I just had to figure out how it translated.

JC: What role did Jewish ritual play in that community?

IK: Almost none… well some. The Bundists and socialists didn’t totally cut themselves off. We celebrated what we considered political holidays, such as Hanukkah, Purim, and Pesach. Those were major holidays for us, but we never did Yom Kippur or Rosh Hashanah, and the first time I stepped into a shul I was in my forties. We also commemorated the Holocaust on April 19th, the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. That was a holiday. I had never heard of Tisha B’av, for example, until I went away to a Jewish camp that used Tisha B’av to talk about the Holocaust. I only really became familiar with religious aspects of Judaism when I became active in the Women’s Movement, and I was forced into it. I was working with women who were observant, and I wanted to be sensitive, so I started learning. A friend and I did a feminist Haggadah. I have a whole bunch of xeroxed Haggadahs with all kinds of goddesses on them.

JC: In your essay “Secular Jewish Identity: Yiddishkayt in America,” you wrote that “the absorption of feminism in to my politics, the recognition of gay oppression represented a major shift in my perspective.” What influenced your feminism? How did you become aware of discrimination toward LGBTQ people?

IK: I became aware of it when I realized that maybe I was gay; nothing does it better than that. I feel I was very lucky, though, because when I came out, which was in 1973, New York was just hopping. It was exploding. It was after Stonewall. Lesbians started getting organized. I belonged to a group of lesbian writers. There were four of us who decided to start Conditions magazine, for example, and before that we had a group called Di Vilde Chayas [the wild animals], which was a group that had Adrienne Rich, Melanie Kay Kantrowitz, Gloria Greenfield, and Evelyn Beck, who did Nice Jewish Girls. Women looked at my background, and they thought, ‘Oh, she’s authentic. She’s the real deal… from Europe, from the War. She’s a child survivor. Wow.’ I just got sucked in.

I was frightened—I mean I got pushback, even in the community in the Bronx; nobody was happy. My mother was not happy. It was difficult, and I did not like being public. It was many many years ago, and I’ve gotten much more comfortable speaking about myself publicly, but at the time, it was very hard.

The Jewish Labor Bund was a non-Zionist organization, so I barely thought about Israel. But if you’re going to be involved with the Left, you’ve got to start thinking about Israel. Melanie and I became very committed to supporting the Women in Black in ‘87. I formed a group here, the Jewish Women’s Committee to End the Occupation (JWCEO) with Clare Kinberg and Grace Paley. We wanted to be identified as Jews protesting.

JC: You write about feeling trapped between two worlds: the Yiddish world and the feminist/lesbian worlds. In what way were these worlds separate? What were some of the barriers to integrating these communities?

IK: When I first came out in the ‘70s, I came out to myself and to friends, but I couldn’t come out in the Jewish world. When I published my first book, I had lesbian poems in there. Some people got it, and some people didn’t. There were people who only wanted to look at my Holocaust poetry. They pretended like there was nothing else. On the other hand, there were lots of lesbians who were just interested in my lesbian poems and could care less about the Holocaust ones. It was very difficult for me to give readings because I never had an integrated audience. It was only many years later, in the ‘90s, when I became better known and would be invited to campuses, for example, that my readings would be co-sponsored by an English department, a women’s center, and an LGBT committee or group. When I did these things, people would always say, ‘Gee, we’ve never had such a mixed audience before.’ In the ‘70s… this was still too raw. Some of it was quite ugly, and it was very disappointing for me to see the community that I had come out of be so bigoted.

JC: What were some of the hostilities that you observed?

IK: First of all, I knew I had to be quiet in order to keep jobs. It was just considered unseemly to be in a relationship with a woman. I certainly couldn’t bring my partner anywhere. I couldn’t talk about my partner. I couldn’t talk about my life. I’m not sure I wanted to talk that much, but I couldn’t be open or casually refer to things. It was very unpleasant and enraging. It’s changed, at least it’s certainly changed here, in New York. The Yiddish world, I sometimes think, is more gay than it is straight at this point.

JC: How did you reconcile the divisions you felt between these worlds?

IK: I didn’t. In a sense you sort of live with that split because it’s not in your control. It’s hard to describe, but you know what the boundaries are without anybody ever saying anything. You’re sort of one person at one moment and another person at another moment. I suppose the only time that you’re ever really complete is when you’re by yourself or in an environment in which you’re not hiding. In the gay community, I was not hiding my Jewishness. Not everybody was interested in my Yiddish work, but nobody was hostile to it. But in the Jewish world, I had to be shut down in certain ways.

JC: What motivated you to found the magazine Conditions, and what was its mission?

IK: The subtitle, which took us probably three months to come up with, was “a feminist magazine of writing by women with a particular emphasis on writing by lesbians.” We wanted to keep it open, but we did want to say there was this emphasis. The four of us were dykes, and our mission was really to publish writing. We had no place to publish, and that was really a problem.

JC: What were some of the biggest challenges in publishing the magazine?

IK: We didn't have money. And it was challenging working with the collective. We were all enthusiastic when we began, but we lived very different lives and didn’t know each other that well. It was a difficult collaboration because we had to work by consensus.

But it was ultimately great because it was a very active period and we cracked it, in the sense that we had newspapers. We had magazines. We had places not only to publish, but also to write reviews and spread the word. There were wonderful presses. It was just great.

JC: In your writing, you weave together English and Yiddish words, sometimes translating the Yiddish words and phrases, and other times leaving them untranslated. What is your intention behind these plays between languages?

IK: Because of where I grew up, I feel very attached to a society and a period that I didn’t live in: inter-war Poland (1918–1939), which is when the Jewish Labor Bund was very active. I always felt sad that I was never able to take part in that world. I think my writing was partly an attempt to bridge that gap. I felt that Yiddish was a really important part of my life, even though I wasn’t necessarily speaking it. Even my politics were fixed in Yiddish. So I started playing with it.

JC: What is it like for you to go back to Poland?

IK: I’ve been there maybe five times. My visits started in ‘83, when I went with my mother, which was her only time going back. It was the 40th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Since then, I’ve been back, and it’s always the same. I go to the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, see a couple of people from my mother’s generation, and that’s about it. This past time, I stayed with these people, who I didn’t know very well, for a month. I traveled to five cities, and I got to know a lot of their friends, Jewish and non-Jewish. A lot of them are progressives and are in opposition to the horrible current government. I probably could get in trouble for saying that; you’re not supposed to denigrate Poland. It was a very interesting trip for me because it was the first time I really dealt with the present in Poland. It’s always been about the past. From that point of view, it was a really wonderful trip, and I’m hoping to go back.

JC: You write that you have always identified as a secular Jew. What does that mean to you?

IK: I feel connected to Jewish history. I feel a part of the Jewish community, in all of its variety. As a Jew, my fate is bound up with other Jews. That could be Hasidim, Sephardim...people who are very different from me. In addition to that sense of bond and commitment, I also feel an obligation to contribute to Jewish culture, and that could take different forms. That could be my own writing, or it could be translations from Yiddish, so that people who don’t speak Yiddish can connect with Ashkenazi tradition. I don’t want Yiddish to disappear because nobody can read it. I also spend a lot of time on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I feel very much that it’s a part of me, in a way; I can’t totally distance myself from it, but I’m deeply disturbed by what’s happened there. I recognize the existence of religious texts, but I don’t necessarily believe them. I appreciate some of them from a literary or historical perspective, and I understand that they’re part of my history as a Jew, but I’m not moved by synagogue. I’m not even sentimental about it.

JC: You have been critical of the Yiddish world’s “refusal to honor Jewish difference,” and you call for greater inclusivity in the Yiddish world. What does that look like? What do you envision as an ideal Jewish community?

IK: We’re very Ashkenazi-centric. I thought about doing a course on the Jewish mother, but I decided not to do it. Practically all of the stuff I found was this Yiddish, Ashkenazi stuff. I thought, ‘Well, what are these other Jewish mothers doing?’ One of the faults of the background that I came from was the thought that they were the Jews. They didn’t really think about the Middle East or other Jews, and if they did, they probably had snotty attitudes toward them. That they were Europeans, and they were superior. There’s got to be a greater knowledge of diversity in Jewish life.

In the Women’s Movement, when we started having women’s seders, we did everything from scratch, and everyone was really happy with that. We’d come together—some of us were religious and some of us weren’t—and have this seder. We’d have these goddesses mimeographed onto Haggadahs and sit on the floor on cushions. It was potluck, so we’d have incredible food. That’s the kind of thing I like. I understand the desire to do the familiar, but there’s another kind of wonderful experience that comes from doing something not so familiar, something that is new and interesting.

I don’t think there is an ideal community—there are different kinds, and it shifts. One of the things we make a mistake about is that we want things to be static. You have to recognize when it’s become confining or rigid or prescriptive. You know, people always forget, Hasidim were considered rebels only 250 years ago. They were excommunicated! Everyone thinks they were around, walking in the desert in Palestine. They weren’t! They don’t realize that it’s much more dynamic. That gives me hope, that things change.

JC: What would you identify as the greatest threats to the preservation and growth of Yiddish culture?

IK: I think there’s a strand of people who say you have to speak Yiddish, and you have to speak it correctly. I don’t want the movement to become elitist. It used to be that Hebrew was the loshon ha-kodesh [holy language]. I don’t want Yiddish to become a holy language. I want it to be of the people, which is the way that it always was. I think that’s something to guard against.

JC: Looking at your 21-year-old self, you wrote “I realize now that I simply did not know how to be an active Jew in the world.” How can one best be “an active Jew in the world” today, in 2018?

IK: I’m not sure I can totally answer that because I don’t feel that in touch with what’s going on. I’m part of an older generation. I think the way to become active as a Jew is to become active, period.

*photo by Robert Giard © Estate of Robert Giard

//JULIA CRAIN is a senior in Barnard College and Literary &.Arts Editor of The Current. She can be reached at [email protected].