// features //

Spring 2016

The Bayit:

A 43-Year-Long Experiment in Jewish Communal Living

Leeza Hirt

Every single night for the past 43 years, a group of 28 students gather around an unusually large table to eat dinner together. They are a diverse bunch, hailing from a variety of backgrounds and an assortment of schools within Columbia University. And yet, they unite around a single table, enjoying the homemade, kosher meal that one of the participants—each night, someone else—has spent hours preparing. Dinner is enlivened with discussion of all sorts of topics: from current events to art and literature, from politics to the latest plot twists in their favorite television shows. They finish eating, wash their dishes on the correct side of the bipartite sink, put them on the designated rack to dry, and go their separate ways. While the world continues to change, this table dinner—a hamlet for pluralistic Jewish thought and conversation—remains a constant: all that has changed about this scene throughout the decades is the cast of characters around the table.

Founded in the fall of 1972, the Bayit, officially known as Beit Ephraim, is a Jewish food co-op located two blocks south of Columbia University’s Morningside campus. Open to full-time Columbia and Barnard undergraduate and graduate students, the residential program houses 28 students living in single rooms. All residents have access to a shared kitchen and dining room, as well as five additional floors of living space. The house affairs are monitored by an elected “executive board,” which oversees finances and programming. House members who are not on the executive board have other forms of ‘toranut’, or duties; they are responsible for household tasks ranging from grocery shopping to cleaning the communal spaces. All members of the house vote on important issues, such as accepting new residents and deliberating the set price of membership to the food fund.

At the heart of the Bayit’s communal living is the requirement that each member must prepare dinner for their fellow residents once a month, though this takes shape as an enjoyable opportunity to bond with fellow housemates rather than a begrudging adherence to community rules. In order to accommodate even the most stringently observant Jews, the dinner must be kosher. To adhere to kosher food preparation standards, the house is equipped with a giant, industrial-sized kitchen, with separate appliances for meat and milk. It has separate ovens, stovetops, sinks, dishes, and silverware. There is one non-kosher fridge and toaster in a separate room for those who do not keep kosher to warm up their food.

But the Bayit is much more than just a kosher diner’s paradise. It has a distinct mission: to function as an “intentional community” dedicated to pluralism and diversity, which aims to provide a warm and welcoming home to Jewish students regardless of their backgrounds and denominations. As its website states: “The Bayit has got heimishe yeshiva bachurim, committed Jewish feminists, egalitarian Conservadox Jews, crunchy Jewish backpackers, secular Israelis, religious Zionists, unaffiliated Jews and many more types all living together under one roof in peace, harmony, and fun. Residents represent a diverse range of academic interests, scholarly pursuits, and ages.”

The Founders: How it all Began

From the early days of the Bayit, the notion of uniting Jewish students of farflung backgrounds under one roof and around the same table was central to its project.

No one remembers exactly who was first to come up with the idea. All agree, though, that the Bayit was a product of its time.

Jewish communal living spaces, called Bayit after the Hebrew word for “home,” were common on American campuses during the early 1970s. As Rabbi Charles Sheer, Columbia’s campus rabbi at that time, wrote in an article in the Sh’ma Journal in 1977: “During the post-'67 War period any Jewish campus worth its salt had a Bayit.” According to Rabbi Sheer, the explosion of Jewish identity after the Six Day War prompted a larger interest in Jewish identity, and activism in general, and the Bayit was a natural outgrowth of this phenomenon.

But its founders think that the idea behind Columbia’s Bayit was even broader than that. The general culture of the late 1960s and early 1970s, with its emphasis on identity politics, activism, and pluralism, lent itself to the foundation of the Bayit. Joseph Wouk, CC’75, CLS’79, a founder of the Bayit, explained: “The idea was for there to be an exchange of ideas among a disparate group of individuals, all about Jewish identity. This made sense in the late 1960s-early 1970s, which was a time of breaking barriers. We thought of it as an anti-fraternity, because the people were so diverse. And it was also a real place—not just a place to live. It was a place to engage and be Jewish in our own way.”

“In the 1970s, there was a lot of concern for doing Jewish things in a Jewish way,” said another founder, Jonathan Groner, CC ’72, CLS ‘75. “Activism was a big deal in general, and this spread to Judaism as well. People wanted to actively live out Jewish ideals—not for it to just be something in a book.”

Groner tied the ideological motivations for the Bayit to the Havura movement, which was also taking root during this time: “Before the Bayit, there were Havurot. The Havurot met for Jewish things, but they didn’t live together. The Bayit was, to some extent, part of that. We remembered the 1960s and were against the establishment. The Bayit was, in many ways, the opposite of the existing organized Jewish community.”

For Wouk, the Bayit sprung out of his feelings of disenchantment with the main activist group on campus: Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). SDS was a national student organization that flourished in the mid-to-late 1960s and specifically focused on activism against the Vietnam War. At Columbia, SDS was instrumental in leading the 1968 student uprising. Although Wouk became president in the early ‘70s, after the heyday of SDS, the club retained much of its radical spirit. After spending his freshman year as president of this student group, Wouk became disillusioned with the radical activist community and decided that he needed to find an alternative ideological community with which he could identify.

Raised in a Modern Orthodox family and having spent a year in Israel before starting Columbia College, Wouk was specifically disappointed with the anti-Zionist nature of SDS: “I was in the process of realizing that radical stuff wasn’t going anywhere for me. Even then, the radical left was associated with anti-Israel stuff. I would say to my group, ‘We’re here to fight the war in Vietnam—why the hell are you talking about the Palestinians?’”

Together with a small group of friends, including (among others) Israel’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Dore Gold, Professor of the Sociology of American Jewry, Steve Cohen, and former literary editor of the New Republic, Leon Wieseltier, Wouk decided to channel his extra time into starting a Jewish house; a project which would lead to the foundation of the Bayit.

In Spring 1972, the group discovered an empty university-owned brownstone on 112th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam. With the financial support of Joseph’s father, Pulitzer-Prize winning novelist Herman Wouk, CC ‘34, and the administrative support of Rabbi Sheer, Wouk acquired the house for use as a Jewish special-interest residence.

After a relatively competitive application and recruitment process—there were far more applicants than spots--a group of 28 diverse Jewish Columbia students moved into the brownstone in Fall 1972. By the Bayit’s second year, admission into the house was so competitive that people started a second Bayit—Bayit Sheni—to accommodate the heavy interest in Jewish student residence communities. This second Bayit was always more tenuous, though, and didn’t last very long. The original Bayit, in contrast, had a sense of permanence about it.

According to Steve Cohen, the founders specifically recruited students who were involved in various forms of activism and Jewish life on campus. “My vision was for there to be a house of activists who would play out their own activism and affect campus. We were all activists with different points of view, and held various sorts of programming in the Bayit.”

Keeping with the Bayit’s dedication to diversity of opinion, the activists were by no means members of the same camp. Among the group were activists for Soviet Jewry, anti-Vietnam War activists, centrist Zionists in the Kadimah student group, left wing Zionists from the Breira group, strictly-observant Orthodox Jews, Conservative Jews, reconstructionist Jews, adamantly secular Jews, anti-religious Jews. Beyond housing this disjoint group of burgeoning activists, the Bayit acted as the nucleus of activist groups, with many of the organizations in which the residents were involved holding meetings in the Bayit. For example, both Kadimah and Breira--pro-Israel groups on opposite sides of the political spectrum--held their weekly meetings in the Bayit; and Orthodox and egalitarian services were regularly held in the Bayit, as were Shabbat dinners and lecture series.

And yet, in spite of such rich programming, the Bayit was not intended to function as the definitive center of Jewish life on campus. Although the campus Hillel (what would later become The Kraft Center for Jewish Student Life) was not yet established, Jewish life at Columbia was already quite robust. Dozens of Jewish groups and organizations were all clustered in a small suite of offices in the basement of Earl Hall. There were religious groups, pro-Israel groups, a Soviet Jewry activist group, a Shabbat Meals Committee. As Wieseltier, CC ‘74, explained: “I never thought the Bayit would take the place of Earl Hall. It wasn’t intended to. It was just a supplement to the Jewish life that already existed on campus.”

So what, then, distinguished the Bayit from the programs offered out of the basement suite in Earl Hall? “We had services sometimes, but that wasn’t the defining feature of the house. The subject matter of what we talked about and lived would be Jewish. We did some studying together of Jewish texts, we ate together—which is, as you know very well, a critical Jewish activity. We were a very lively community. We weren’t a bunch of separatists separating from the outside world—it was nothing like that. But being Jewish together was the point. There were so many types of Jews, that this turned out to be much more complicated than we thought it might be.”

The element of the Bayit which would serve as its most appealing and defining attribute—a commitment to the broadest definition of Jewishness and Jewish life––would also signify the central tensions that pulled at the delicately sewn fabric of the Bayit’s community. As with any organization comprised of many strong personalities with different philosophies of life, the Bayit was not an easy experiment. There were countless conflicts and discordances, especially at the beginning.

The Early Days: Points of Contention and Sources of Unity

Amy Millard, BC ’73, recounted the early days of the Bayit: “Right when we moved into the empty brownstone, we had hours-long meetings where we set up the rules. Because this was going to be a place where all Jews could live together, there were lots of rules about Shabbos. It was our sense that if this would be open to all of us, the only rule should be that we must have a kosher kitchen. It all worked, actually, but not without conflict.”

Wouk recounts one particular conflict that arose between the religious and secular Jews living in the Bayit: “In Columbia, and especially in the Bayit, I was a trouble maker. I was anti-religious. Whenever the Orthodox residents in the Bayit tried to impose a religious edict, I would oppose it. For example, when we first moved in, they said that everyone has to put a mezuzah on their door. I said, you can put it on the door to the house and your own doors, but I’m not going to put it on my door—I don’t believe in that stuff. But I got voted down. They gave out the klafs [the scrolls with the text that goes inside the box, which is affixed to doorposts] and I got a nice wooden mezuzah box and carved into it, ‘God is dead.’ I was saying to them, ‘Don’t fuck with me.’ We had another house meeting and I was censured. But that was my role! I was anti-authoritarian. It’s not that any one person was authoritarian, per se, but religion is by definition, authoritarian.”

Despite diversity in political opinion and religious observance among the original cohort of the Bayit, there was one unifying feature of the house: all were Israel supporters. There were Israeli flags all around the house, and pro-Israel student groups regularly held their meetings there. In Millard’s words, “Israel was a natural part of our identities. We all supported Israel and we supported each other. That was the absolute assumption.”

This does not mean that there was no diversity of opinion when it came to Israel. To the contrary: members of the Bayit held very diverse views regarding Israel, but all supported the Jewish right to self-determination in the land of Israel.

As Cohen puts it, many Israel-involved people from across the political spectrum emerged from the early days of the Bayit. From that first cohort alone, at least a dozen people moved to Israel after graduating. Among those Bayit members who moved to Israel are right-wing settlers who live in Hebron, and left-wing Meretz voters like Cohen, “who think the settlements are destroying Israel.” This is a perfect microcosm of the diversity of opinion in the Bayit.

In 1972, just as today, Israel discourse was pervasive on campus. “Fighting for Israel was part of what we did. There was a very intense Israel-consciousness on campus in general and especially in the Bayit,” said Wieseltier. Wieseltier was very involved in the political conversation about Israel on campus. He was in charge of Kadima, a Zionist pro-Israel group, and active in the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. He regularly engaged in public debate with other students about Israel and Palestine. “But the Bayit was a retreat from campus in this way, rather than an extension of campus.” It was a place where support for Israel was a given, and where supporters of Israel, who often felt attacked on campus, could let their guard down.

This is one aspect of the Bayit that is noticeably very different today.

The Bayit Today: More Diverse Than Ever?

Today, the Bayit retains much of the pluralistic spirit of its founders. The kitchen is still kosher, the communal meals still occur, and all sorts of Jews still live there. But, in accordance with larger trends in the American Jewish community, support for Israel is no longer a given. In fact, the President of Columbia’s chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace, a Jewish pro-BDS group, Eva Kalikoff, BC ‘16, just moved into the Bayit this semester.

In the Bayit, BDS activists like Eva and pro-Israel IDF veterans share walls and kitchen appliances relatively peacefully. However, it is not a peace built on discussion and dialogue. Rather, it is a carefully orchestrated peace largely built upon deliberate silence about the contested topic in communal spaces altogether.

While conversation about Israel certainly occurs in small groups in the house, it is rarely, if ever, the subject of discussion at the dinner table or in the common areas. No one would dream of hanging an Israeli flag or holding a pro-Israel or anti-Israel group meeting in the shared spaces.

Tali Lefkowitz, BC ’16, an IDF Veteran and pro-Israel advocate on campus, said that she is afraid to talk about Israel in the house. After completing her service in the army, Lefkowitz was conflicted about where she fit in Jewishly on campus. She didn’t immediately assimilate into the Orthodox community, but still yearned for an immersive Jewish environment. The Bayit seemed like the right place to make that transition—it would be a good way to balance her involvement in the homogenous Orthodox community with a more diverse Jewish experience, much like the one she had in Israel. She had heard that the Bayit was an Israel-oriented place, functioning as an urban kibbutz, with a sort of Israeli ethos. From the outside, the historic brownstone initially seemed like the perfect place for her post-army life.

“I had hoped that the Bayit would be an extension of my Israel experience, but that was not what I found,” said Lefkowitz. Instead, she has found that she is hesitant to talk about Israel in the house at all. Although she has yet to clash with residents who do not share her beliefs, this is because she has largely avoided discussing this issue with them altogether.

Another pro-Israel resident, Alexander Wold, a graduate student in the Actuarial Science program, whose sister is currently serving in the IDF, said that he also avoids talking about Israel in the house. “I am too saddened by the pro-BDS opinion to even have a conversation with its supporters about it. I don’t want to approach this because I know it won’t end well. I wouldn’t be able to separate my emotions from my argument.”

According to some other members of the Bayit, discussion of Israel is quite pervasive in the Bayit—it is just not occurring in the public sphere for intentional reasons.

As Kalikoff put it, “I don’t think that Israel is taboo in the Bayit. We talk about it individually. I’ve had great conversations with plenty of people on my own. I feel totally comfortable talking about it, but it just isn’t the focus of the house.”

Kalikoff is impressed by how cordial members of the house have been towards her, despite the rising hostility on campus between the pro-Israel and anti-Israel factions as the BDS movement came to the fore. While she suspected her pro-Israel housemates would bring campus politics into the house, this has not been the case.

“Tali Lefkowitz is a good example,” Kalikoff said. “We knew each other before as opposing political characters on campus. We had never spoken on a personal level. I made a point to be very open about my activism and work. I sent an email to everyone when I moved in. Tali responded right away and living with her has been very comfortable. I’m happily surprised to be able to live with her normally.”

Another Bayit member, Daniel First, GSAS ‘18, agrees that discussion about Israel is definitely not absent from the Bayit—it is just not discussed at the dinner table because it would be more divisive than productive.

“People do think and talk about Israel a lot, but it's uncommon for Israel to be debated at the dinner table of twenty. There's a general understanding that smaller conversations are more productive for discussing contentious topics.”

Jesse Gruber, GS ‘16, thinks that the lack of conversation about Israel is not a problem specific to the Bayit, but is symptomatic of the current state of the American Jewish community in general. “I think there is a hesitance to talk about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the house. Absolutely. But I don’t think that is specific to the Bayit. People in general are nervous about losing friends when they talk about Israel. It is a real problem. The Jews I’ve met here at Columbia in general are scared to talk about Israel. This leads me to be more uninformed than I would be otherwise.”

However, Gruber concedes that this problem is even more pronounced in the Bayit than it is in other Jewish environments: “People here are especially scared to talk about Israel because we live together and don’t want to make enemies in the house. But this fear doesn’t apply when we talk about other issues like Obamacare and abortion.”

“There is a lot of talk like, ‘I’ve had a really bad day, I don’t want to talk about Israel.’”

The original residents of the Bayit were interested to hear about how the Bayit was faring today, specifically as it pertains to conversation about Israel. Some were dismayed to learn that the president of Jewish Voice for Peace lives in the house, while others, though they disagree with JVP’s politics, were glad that the house is truly upholding its pluralistic mission.

Wieseltier said, “Maybe the less people talk about the status of Jerusalem, the better the status of Jerusalem will be. If I were there now, I would say that the JVP person should be included, even though I detest what they represent.”

One has to wonder, though, whether the intentional silence on Israel at the Bayit is causing it to become a prototypical “safe space,” in which people refrain from engaging in real conversations out of fear of insulting or alienating others. In avoiding this contentious topic in public spaces in order to maintain civility, is the Bayit increasingly becoming the very environment it is supposed to reject? Or are the smaller, more personal conversations about Israel that occur in the Bayit a more productive—and not any less valuable—way of engaging with the ideas of others?

The Bayit Today: Continuing the Legacy

Despite the relative tension when it comes to Israel, the Bayit remains a warm, comforting place to return to each day.

For Gruber, it is mostly about the food. “Honestly, the biggest plus for me in the Bayit is the food. It is so satisfying to see 28 people eating something you slaved over for nine hours. Economically, it is great. It comes out to about five dollars a day for food, which is way less than I would be paying for a meal plan. And every night I come home to a ready, home-cooked meal, and 20 people to sit and talk to—not about Israel.”

But for others, the food is just the pretext that enables the formation of a deep community.

“When I moved in, I was happy to find that there were a number of humanities majors in the house,” said First. “Everyone is very broadly interested in different topics. We have some really thoughtful, amazing discussions. We read fiction books together for a Bayit book club. People move in because they are interested in discussions with other people.”

The Jewish ritual aspects of the Bayit also provide an important forum for residents to bond with one another. They build a sukkah every year for the fall holiday in the dinky alley between the Bayit and its neighboring fraternity townhouses, endowing the space with aesthetic and spiritual beauty. They scrub the kitchen together in preparation for Passover, light the Chanukah candles together, host shabbat meals every week, and sometimes sing Havdala together to mark the end of shabbat.

But the ritual component of the Bayit presents a unique set of challenges.

If it were up to Sarah Kravinsky, BC ’18 and head of recruitment for the Bayit, the Bayit would not be stringent about keeping kosher--it would probably focus on ethical eating as a manifestation of kashrut. But she wants every Jew to feel comfortable eating at the Bayit, which is why she chooses to put up with the inconvenience.

“I didn’t know how much I didn’t know about living with observant people. I had a very Jewish childhood, but never halakhic. I went to public school, and was always part of a lefty/secular Jewish community,” Kravinsky said.

Apart from adjustments in dietary habits and religious customs, Kravinsky celebrates the extent to which her housemates push her to fully contemplate and defend the complexities of her opinions (music to the founding members’ ears!): “In the Bayit, I’m learning what it means to take responsibility for all Jewish people, not just people I’m similar to. Before coming here, I thought I had good conversational and confrontational skills, and they have definitely been put to use and improved here. I’m always tested with people I’m different from.”

For the past 43 years, the Bayit has been an experiment in Jewish pluralism. Through living with people who hold ideas and beliefs that are genuinely different from—and sometimes opposed to—one another, Bayit members learn that true pluralism is not just about coexistence, but is also about choosing to engage with people’s beliefs even if this might be painful.

Most people do not have the opportunity to engage deeply with the opinions of others. Even at a university like Columbia, which celebrates the diversity of its student body, it is possible for students to go through their entire education without confronting points of view that they truly dislike. From its inception, the Bayit has always been the exception to this rule: a space where people who disagree with one another deliberately live together and embrace their differences; where Jews—Orthodox and secular, liberal and conservative, and everything in between—build a community unlike any other.

“How did we do it in the Bayit? How did we all live together? I think about this all the time,” Millard said. For her, they managed to live together by subscribing to the “underlying premise that everyone believed that each of our ways was legitimately Jewish.”

As the Bayit becomes increasingly diverse, its members must ask themselves, who gets to decide what is considered legitimately Jewish and how do they come to that conclusion? This question is not confined to a single brownstone on 112th street, but is the same question that haunts the organized Jewish establishment; from Hillel to the State of Israel. At stake in the Bayit, as in these other groups, is the legitimation of one’s membership to the Jewish community.

It seems that the Bayit deliberately leaves this question unanswered--leaving room for each generation of students to answer it through experience. In this trial and error format, there is no single test of Jewishness that serves as a criterion for who should live in the Bayit. This rejection of a homogenous residency sustains the Bayit’s legacy as a refuge for rigorous intellectualism and pluralistic thought. And when after 43 years the Bayit has yet to see a day when a Kosher dinner isn’t served and meaningful conversation (whether in small, quiet chats or rambunctious debates at the dining room table) isn’t had, perhaps it is time to shed the tenuous, cautionary language of “experiment” when discussing the Bayit, and more apt to celebrate it as a permanent, crucial aspect of Jewish life at Columbia.

Founded in the fall of 1972, the Bayit, officially known as Beit Ephraim, is a Jewish food co-op located two blocks south of Columbia University’s Morningside campus. Open to full-time Columbia and Barnard undergraduate and graduate students, the residential program houses 28 students living in single rooms. All residents have access to a shared kitchen and dining room, as well as five additional floors of living space. The house affairs are monitored by an elected “executive board,” which oversees finances and programming. House members who are not on the executive board have other forms of ‘toranut’, or duties; they are responsible for household tasks ranging from grocery shopping to cleaning the communal spaces. All members of the house vote on important issues, such as accepting new residents and deliberating the set price of membership to the food fund.

At the heart of the Bayit’s communal living is the requirement that each member must prepare dinner for their fellow residents once a month, though this takes shape as an enjoyable opportunity to bond with fellow housemates rather than a begrudging adherence to community rules. In order to accommodate even the most stringently observant Jews, the dinner must be kosher. To adhere to kosher food preparation standards, the house is equipped with a giant, industrial-sized kitchen, with separate appliances for meat and milk. It has separate ovens, stovetops, sinks, dishes, and silverware. There is one non-kosher fridge and toaster in a separate room for those who do not keep kosher to warm up their food.

But the Bayit is much more than just a kosher diner’s paradise. It has a distinct mission: to function as an “intentional community” dedicated to pluralism and diversity, which aims to provide a warm and welcoming home to Jewish students regardless of their backgrounds and denominations. As its website states: “The Bayit has got heimishe yeshiva bachurim, committed Jewish feminists, egalitarian Conservadox Jews, crunchy Jewish backpackers, secular Israelis, religious Zionists, unaffiliated Jews and many more types all living together under one roof in peace, harmony, and fun. Residents represent a diverse range of academic interests, scholarly pursuits, and ages.”

The Founders: How it all Began

From the early days of the Bayit, the notion of uniting Jewish students of farflung backgrounds under one roof and around the same table was central to its project.

No one remembers exactly who was first to come up with the idea. All agree, though, that the Bayit was a product of its time.

Jewish communal living spaces, called Bayit after the Hebrew word for “home,” were common on American campuses during the early 1970s. As Rabbi Charles Sheer, Columbia’s campus rabbi at that time, wrote in an article in the Sh’ma Journal in 1977: “During the post-'67 War period any Jewish campus worth its salt had a Bayit.” According to Rabbi Sheer, the explosion of Jewish identity after the Six Day War prompted a larger interest in Jewish identity, and activism in general, and the Bayit was a natural outgrowth of this phenomenon.

But its founders think that the idea behind Columbia’s Bayit was even broader than that. The general culture of the late 1960s and early 1970s, with its emphasis on identity politics, activism, and pluralism, lent itself to the foundation of the Bayit. Joseph Wouk, CC’75, CLS’79, a founder of the Bayit, explained: “The idea was for there to be an exchange of ideas among a disparate group of individuals, all about Jewish identity. This made sense in the late 1960s-early 1970s, which was a time of breaking barriers. We thought of it as an anti-fraternity, because the people were so diverse. And it was also a real place—not just a place to live. It was a place to engage and be Jewish in our own way.”

“In the 1970s, there was a lot of concern for doing Jewish things in a Jewish way,” said another founder, Jonathan Groner, CC ’72, CLS ‘75. “Activism was a big deal in general, and this spread to Judaism as well. People wanted to actively live out Jewish ideals—not for it to just be something in a book.”

Groner tied the ideological motivations for the Bayit to the Havura movement, which was also taking root during this time: “Before the Bayit, there were Havurot. The Havurot met for Jewish things, but they didn’t live together. The Bayit was, to some extent, part of that. We remembered the 1960s and were against the establishment. The Bayit was, in many ways, the opposite of the existing organized Jewish community.”

For Wouk, the Bayit sprung out of his feelings of disenchantment with the main activist group on campus: Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). SDS was a national student organization that flourished in the mid-to-late 1960s and specifically focused on activism against the Vietnam War. At Columbia, SDS was instrumental in leading the 1968 student uprising. Although Wouk became president in the early ‘70s, after the heyday of SDS, the club retained much of its radical spirit. After spending his freshman year as president of this student group, Wouk became disillusioned with the radical activist community and decided that he needed to find an alternative ideological community with which he could identify.

Raised in a Modern Orthodox family and having spent a year in Israel before starting Columbia College, Wouk was specifically disappointed with the anti-Zionist nature of SDS: “I was in the process of realizing that radical stuff wasn’t going anywhere for me. Even then, the radical left was associated with anti-Israel stuff. I would say to my group, ‘We’re here to fight the war in Vietnam—why the hell are you talking about the Palestinians?’”

Together with a small group of friends, including (among others) Israel’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Dore Gold, Professor of the Sociology of American Jewry, Steve Cohen, and former literary editor of the New Republic, Leon Wieseltier, Wouk decided to channel his extra time into starting a Jewish house; a project which would lead to the foundation of the Bayit.

In Spring 1972, the group discovered an empty university-owned brownstone on 112th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam. With the financial support of Joseph’s father, Pulitzer-Prize winning novelist Herman Wouk, CC ‘34, and the administrative support of Rabbi Sheer, Wouk acquired the house for use as a Jewish special-interest residence.

After a relatively competitive application and recruitment process—there were far more applicants than spots--a group of 28 diverse Jewish Columbia students moved into the brownstone in Fall 1972. By the Bayit’s second year, admission into the house was so competitive that people started a second Bayit—Bayit Sheni—to accommodate the heavy interest in Jewish student residence communities. This second Bayit was always more tenuous, though, and didn’t last very long. The original Bayit, in contrast, had a sense of permanence about it.

According to Steve Cohen, the founders specifically recruited students who were involved in various forms of activism and Jewish life on campus. “My vision was for there to be a house of activists who would play out their own activism and affect campus. We were all activists with different points of view, and held various sorts of programming in the Bayit.”

Keeping with the Bayit’s dedication to diversity of opinion, the activists were by no means members of the same camp. Among the group were activists for Soviet Jewry, anti-Vietnam War activists, centrist Zionists in the Kadimah student group, left wing Zionists from the Breira group, strictly-observant Orthodox Jews, Conservative Jews, reconstructionist Jews, adamantly secular Jews, anti-religious Jews. Beyond housing this disjoint group of burgeoning activists, the Bayit acted as the nucleus of activist groups, with many of the organizations in which the residents were involved holding meetings in the Bayit. For example, both Kadimah and Breira--pro-Israel groups on opposite sides of the political spectrum--held their weekly meetings in the Bayit; and Orthodox and egalitarian services were regularly held in the Bayit, as were Shabbat dinners and lecture series.

And yet, in spite of such rich programming, the Bayit was not intended to function as the definitive center of Jewish life on campus. Although the campus Hillel (what would later become The Kraft Center for Jewish Student Life) was not yet established, Jewish life at Columbia was already quite robust. Dozens of Jewish groups and organizations were all clustered in a small suite of offices in the basement of Earl Hall. There were religious groups, pro-Israel groups, a Soviet Jewry activist group, a Shabbat Meals Committee. As Wieseltier, CC ‘74, explained: “I never thought the Bayit would take the place of Earl Hall. It wasn’t intended to. It was just a supplement to the Jewish life that already existed on campus.”

So what, then, distinguished the Bayit from the programs offered out of the basement suite in Earl Hall? “We had services sometimes, but that wasn’t the defining feature of the house. The subject matter of what we talked about and lived would be Jewish. We did some studying together of Jewish texts, we ate together—which is, as you know very well, a critical Jewish activity. We were a very lively community. We weren’t a bunch of separatists separating from the outside world—it was nothing like that. But being Jewish together was the point. There were so many types of Jews, that this turned out to be much more complicated than we thought it might be.”

The element of the Bayit which would serve as its most appealing and defining attribute—a commitment to the broadest definition of Jewishness and Jewish life––would also signify the central tensions that pulled at the delicately sewn fabric of the Bayit’s community. As with any organization comprised of many strong personalities with different philosophies of life, the Bayit was not an easy experiment. There were countless conflicts and discordances, especially at the beginning.

The Early Days: Points of Contention and Sources of Unity

Amy Millard, BC ’73, recounted the early days of the Bayit: “Right when we moved into the empty brownstone, we had hours-long meetings where we set up the rules. Because this was going to be a place where all Jews could live together, there were lots of rules about Shabbos. It was our sense that if this would be open to all of us, the only rule should be that we must have a kosher kitchen. It all worked, actually, but not without conflict.”

Wouk recounts one particular conflict that arose between the religious and secular Jews living in the Bayit: “In Columbia, and especially in the Bayit, I was a trouble maker. I was anti-religious. Whenever the Orthodox residents in the Bayit tried to impose a religious edict, I would oppose it. For example, when we first moved in, they said that everyone has to put a mezuzah on their door. I said, you can put it on the door to the house and your own doors, but I’m not going to put it on my door—I don’t believe in that stuff. But I got voted down. They gave out the klafs [the scrolls with the text that goes inside the box, which is affixed to doorposts] and I got a nice wooden mezuzah box and carved into it, ‘God is dead.’ I was saying to them, ‘Don’t fuck with me.’ We had another house meeting and I was censured. But that was my role! I was anti-authoritarian. It’s not that any one person was authoritarian, per se, but religion is by definition, authoritarian.”

Despite diversity in political opinion and religious observance among the original cohort of the Bayit, there was one unifying feature of the house: all were Israel supporters. There were Israeli flags all around the house, and pro-Israel student groups regularly held their meetings there. In Millard’s words, “Israel was a natural part of our identities. We all supported Israel and we supported each other. That was the absolute assumption.”

This does not mean that there was no diversity of opinion when it came to Israel. To the contrary: members of the Bayit held very diverse views regarding Israel, but all supported the Jewish right to self-determination in the land of Israel.

As Cohen puts it, many Israel-involved people from across the political spectrum emerged from the early days of the Bayit. From that first cohort alone, at least a dozen people moved to Israel after graduating. Among those Bayit members who moved to Israel are right-wing settlers who live in Hebron, and left-wing Meretz voters like Cohen, “who think the settlements are destroying Israel.” This is a perfect microcosm of the diversity of opinion in the Bayit.

In 1972, just as today, Israel discourse was pervasive on campus. “Fighting for Israel was part of what we did. There was a very intense Israel-consciousness on campus in general and especially in the Bayit,” said Wieseltier. Wieseltier was very involved in the political conversation about Israel on campus. He was in charge of Kadima, a Zionist pro-Israel group, and active in the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. He regularly engaged in public debate with other students about Israel and Palestine. “But the Bayit was a retreat from campus in this way, rather than an extension of campus.” It was a place where support for Israel was a given, and where supporters of Israel, who often felt attacked on campus, could let their guard down.

This is one aspect of the Bayit that is noticeably very different today.

The Bayit Today: More Diverse Than Ever?

Today, the Bayit retains much of the pluralistic spirit of its founders. The kitchen is still kosher, the communal meals still occur, and all sorts of Jews still live there. But, in accordance with larger trends in the American Jewish community, support for Israel is no longer a given. In fact, the President of Columbia’s chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace, a Jewish pro-BDS group, Eva Kalikoff, BC ‘16, just moved into the Bayit this semester.

In the Bayit, BDS activists like Eva and pro-Israel IDF veterans share walls and kitchen appliances relatively peacefully. However, it is not a peace built on discussion and dialogue. Rather, it is a carefully orchestrated peace largely built upon deliberate silence about the contested topic in communal spaces altogether.

While conversation about Israel certainly occurs in small groups in the house, it is rarely, if ever, the subject of discussion at the dinner table or in the common areas. No one would dream of hanging an Israeli flag or holding a pro-Israel or anti-Israel group meeting in the shared spaces.

Tali Lefkowitz, BC ’16, an IDF Veteran and pro-Israel advocate on campus, said that she is afraid to talk about Israel in the house. After completing her service in the army, Lefkowitz was conflicted about where she fit in Jewishly on campus. She didn’t immediately assimilate into the Orthodox community, but still yearned for an immersive Jewish environment. The Bayit seemed like the right place to make that transition—it would be a good way to balance her involvement in the homogenous Orthodox community with a more diverse Jewish experience, much like the one she had in Israel. She had heard that the Bayit was an Israel-oriented place, functioning as an urban kibbutz, with a sort of Israeli ethos. From the outside, the historic brownstone initially seemed like the perfect place for her post-army life.

“I had hoped that the Bayit would be an extension of my Israel experience, but that was not what I found,” said Lefkowitz. Instead, she has found that she is hesitant to talk about Israel in the house at all. Although she has yet to clash with residents who do not share her beliefs, this is because she has largely avoided discussing this issue with them altogether.

Another pro-Israel resident, Alexander Wold, a graduate student in the Actuarial Science program, whose sister is currently serving in the IDF, said that he also avoids talking about Israel in the house. “I am too saddened by the pro-BDS opinion to even have a conversation with its supporters about it. I don’t want to approach this because I know it won’t end well. I wouldn’t be able to separate my emotions from my argument.”

According to some other members of the Bayit, discussion of Israel is quite pervasive in the Bayit—it is just not occurring in the public sphere for intentional reasons.

As Kalikoff put it, “I don’t think that Israel is taboo in the Bayit. We talk about it individually. I’ve had great conversations with plenty of people on my own. I feel totally comfortable talking about it, but it just isn’t the focus of the house.”

Kalikoff is impressed by how cordial members of the house have been towards her, despite the rising hostility on campus between the pro-Israel and anti-Israel factions as the BDS movement came to the fore. While she suspected her pro-Israel housemates would bring campus politics into the house, this has not been the case.

“Tali Lefkowitz is a good example,” Kalikoff said. “We knew each other before as opposing political characters on campus. We had never spoken on a personal level. I made a point to be very open about my activism and work. I sent an email to everyone when I moved in. Tali responded right away and living with her has been very comfortable. I’m happily surprised to be able to live with her normally.”

Another Bayit member, Daniel First, GSAS ‘18, agrees that discussion about Israel is definitely not absent from the Bayit—it is just not discussed at the dinner table because it would be more divisive than productive.

“People do think and talk about Israel a lot, but it's uncommon for Israel to be debated at the dinner table of twenty. There's a general understanding that smaller conversations are more productive for discussing contentious topics.”

Jesse Gruber, GS ‘16, thinks that the lack of conversation about Israel is not a problem specific to the Bayit, but is symptomatic of the current state of the American Jewish community in general. “I think there is a hesitance to talk about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the house. Absolutely. But I don’t think that is specific to the Bayit. People in general are nervous about losing friends when they talk about Israel. It is a real problem. The Jews I’ve met here at Columbia in general are scared to talk about Israel. This leads me to be more uninformed than I would be otherwise.”

However, Gruber concedes that this problem is even more pronounced in the Bayit than it is in other Jewish environments: “People here are especially scared to talk about Israel because we live together and don’t want to make enemies in the house. But this fear doesn’t apply when we talk about other issues like Obamacare and abortion.”

“There is a lot of talk like, ‘I’ve had a really bad day, I don’t want to talk about Israel.’”

The original residents of the Bayit were interested to hear about how the Bayit was faring today, specifically as it pertains to conversation about Israel. Some were dismayed to learn that the president of Jewish Voice for Peace lives in the house, while others, though they disagree with JVP’s politics, were glad that the house is truly upholding its pluralistic mission.

Wieseltier said, “Maybe the less people talk about the status of Jerusalem, the better the status of Jerusalem will be. If I were there now, I would say that the JVP person should be included, even though I detest what they represent.”

One has to wonder, though, whether the intentional silence on Israel at the Bayit is causing it to become a prototypical “safe space,” in which people refrain from engaging in real conversations out of fear of insulting or alienating others. In avoiding this contentious topic in public spaces in order to maintain civility, is the Bayit increasingly becoming the very environment it is supposed to reject? Or are the smaller, more personal conversations about Israel that occur in the Bayit a more productive—and not any less valuable—way of engaging with the ideas of others?

The Bayit Today: Continuing the Legacy

Despite the relative tension when it comes to Israel, the Bayit remains a warm, comforting place to return to each day.

For Gruber, it is mostly about the food. “Honestly, the biggest plus for me in the Bayit is the food. It is so satisfying to see 28 people eating something you slaved over for nine hours. Economically, it is great. It comes out to about five dollars a day for food, which is way less than I would be paying for a meal plan. And every night I come home to a ready, home-cooked meal, and 20 people to sit and talk to—not about Israel.”

But for others, the food is just the pretext that enables the formation of a deep community.

“When I moved in, I was happy to find that there were a number of humanities majors in the house,” said First. “Everyone is very broadly interested in different topics. We have some really thoughtful, amazing discussions. We read fiction books together for a Bayit book club. People move in because they are interested in discussions with other people.”

The Jewish ritual aspects of the Bayit also provide an important forum for residents to bond with one another. They build a sukkah every year for the fall holiday in the dinky alley between the Bayit and its neighboring fraternity townhouses, endowing the space with aesthetic and spiritual beauty. They scrub the kitchen together in preparation for Passover, light the Chanukah candles together, host shabbat meals every week, and sometimes sing Havdala together to mark the end of shabbat.

But the ritual component of the Bayit presents a unique set of challenges.

If it were up to Sarah Kravinsky, BC ’18 and head of recruitment for the Bayit, the Bayit would not be stringent about keeping kosher--it would probably focus on ethical eating as a manifestation of kashrut. But she wants every Jew to feel comfortable eating at the Bayit, which is why she chooses to put up with the inconvenience.

“I didn’t know how much I didn’t know about living with observant people. I had a very Jewish childhood, but never halakhic. I went to public school, and was always part of a lefty/secular Jewish community,” Kravinsky said.

Apart from adjustments in dietary habits and religious customs, Kravinsky celebrates the extent to which her housemates push her to fully contemplate and defend the complexities of her opinions (music to the founding members’ ears!): “In the Bayit, I’m learning what it means to take responsibility for all Jewish people, not just people I’m similar to. Before coming here, I thought I had good conversational and confrontational skills, and they have definitely been put to use and improved here. I’m always tested with people I’m different from.”

For the past 43 years, the Bayit has been an experiment in Jewish pluralism. Through living with people who hold ideas and beliefs that are genuinely different from—and sometimes opposed to—one another, Bayit members learn that true pluralism is not just about coexistence, but is also about choosing to engage with people’s beliefs even if this might be painful.

Most people do not have the opportunity to engage deeply with the opinions of others. Even at a university like Columbia, which celebrates the diversity of its student body, it is possible for students to go through their entire education without confronting points of view that they truly dislike. From its inception, the Bayit has always been the exception to this rule: a space where people who disagree with one another deliberately live together and embrace their differences; where Jews—Orthodox and secular, liberal and conservative, and everything in between—build a community unlike any other.

“How did we do it in the Bayit? How did we all live together? I think about this all the time,” Millard said. For her, they managed to live together by subscribing to the “underlying premise that everyone believed that each of our ways was legitimately Jewish.”

As the Bayit becomes increasingly diverse, its members must ask themselves, who gets to decide what is considered legitimately Jewish and how do they come to that conclusion? This question is not confined to a single brownstone on 112th street, but is the same question that haunts the organized Jewish establishment; from Hillel to the State of Israel. At stake in the Bayit, as in these other groups, is the legitimation of one’s membership to the Jewish community.

It seems that the Bayit deliberately leaves this question unanswered--leaving room for each generation of students to answer it through experience. In this trial and error format, there is no single test of Jewishness that serves as a criterion for who should live in the Bayit. This rejection of a homogenous residency sustains the Bayit’s legacy as a refuge for rigorous intellectualism and pluralistic thought. And when after 43 years the Bayit has yet to see a day when a Kosher dinner isn’t served and meaningful conversation (whether in small, quiet chats or rambunctious debates at the dining room table) isn’t had, perhaps it is time to shed the tenuous, cautionary language of “experiment” when discussing the Bayit, and more apt to celebrate it as a permanent, crucial aspect of Jewish life at Columbia.

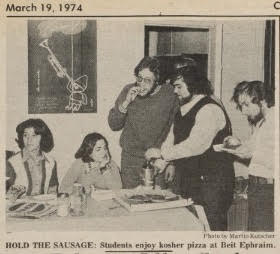

\\ LEEZA HIRT is a sophomore in Columbia College and Features Editor for The Current. She can be reached at [email protected]. Photo courtesy of the Columbia Spectator Archives.