//literary and arts//

Spring 2019

Spring 2019

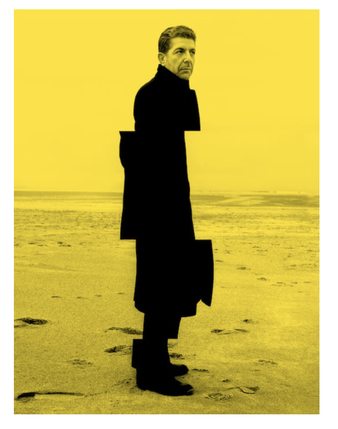

"A Crack in Everything":

The Light of Leonard Cohen

Gidon Halbfinger

“Forget your perfect offerings. There’s a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

I still remember the day my father looked at me and spoke those words. It was three years ago; he was driving our beat-up Honda Pilot down the cracked city streets near our house in Washington, DC. I was sitting in the passenger seat, listening to his screed on the injustice of Bob Dylan receiving the Nobel Prize in literature. Dylan had become the first musician ever to do so, while Leonard Cohen’s romantic, heart wrenching, powerfully human expressions of divine beauty went unrecognized. How could Dylan’s songs be considered a greater contribution to literature than Cohen’s incisive commentary on the imperfection of man and his striving for love and grace?

Three years later, I found myself again discussing Cohen with my father, in the New York Jewish Museum’s new exhibit, “Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything.” Finally, this great artist was being recognized; much of the museum had been transformed into a temple of sorts to Cohen. And, in many ways, the temple was a fitting one: the ground floor of the museum had become a catacomb of darkened rooms, each showcasing a different artist’s audiovisual ode to Cohen. The result was an aura of somber, quiet listening and watching as Cohen’s mellifluous voice echoed in each chamber; the focus, of course, was on the man himself.

But, as The Guardian recently put it, the exhibit reveals Cohen only “through the eyes of others.” The effect can be a disjointed mess: some of the exhibits ranged from kitschy to off-putting and downright bizarre. Cohen – at least to me – was none of those things. The experience was a stark reminder that when viewing one artist through the lens of another, one risks a cloudy lens. It was difficult to see Cohen underneath the abstract shapes and rough animation of Kota Ezawa’s digital projection in “Cohen 21,” which was accompanied not by music or poetry but by the audio of the 1965 documentary Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen. It was difficult to hear Cohen in Christophe Chassol’s eerie, spectral “Cuba in Cohen,” which combined Cohen’s voice with several others reciting his poem “The Only Tourist in Havana.” And though the exhibit’s general creepiness was limited to the first floor, the comparatively bright second floor swung to the opposite extreme, presenting a cheap, commercialized version. Coming out of the elevator, one comes face to Tacita Dean’s “Ear on a Worm,” a three minute, thirty three second long film of a bird on a wire in homage to the Cohen piece of that name and length. This work has none of the depth, sorrow, and poetry of Cohen’s song. Where is the drunk in the midnight choir?

Perhaps the worst offender was art and design studio Daily Tous Les Jours’ “I Heard There was a Secret Chord,” which asked visitors to perch themselves on an octagonal bench and hum into one of the several dozen microphones hanging from the ceiling. In the background, a computer-generated simulation of hundreds of voices humming Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” with more voices added to the chorus depending on how many people are currently listening to the studio’s online radio station, asecretchord.com. Humming into the microphone causes the bench to vibrate, “closing the circuit” of kitschy, lifeless, robotic, repetitive meaninglessness. This was not Cohen, in all his depth, warmth, and romantic longing; this was not even human, which is perhaps what Cohen was above all else. This was corporate, computerized, and devoid of poetry.

The entire exhibit was saved, however, by the museum’s highest level. On the third floor I experienced “Listening to Leonard,” an hour-and-a-half long audio track comprised of covers of Cohen’s greatest hits by a range of contemporary artists. This was Cohen, in his own words and his own melodies; rather than experiencing him through another artist’s eyes, I was experiencing him through their voices. The songs played in a darkened room, with a single colored bar projected on one wall and dancing to the music, not assertive enough to detract from the auditory experience. Beanbag cushions were arranged on the floor, encouraging visitors to lie down on the ground, close their eyes, and be sublated into the music. Sufjan Stevens and The National delivered “Memories” in haunting fashion – not ghostly haunting, like the first floor exhibits, but humanly, passionately haunting. Ariane Moffatt and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra produced a full, emotional, heart-poundingly beautiful “Famous Blue Raincoat.” Dear Criminals covered “Anthem.” As I lay, motionless, next to my father, I was transported back three years. The museum fell away; the kitsch and the darkness and the commodification of beauty sank as I rose. Despite the museum’s flaws, I felt uplifted, consumed, raised by the music. Cohen’s words, sung by others, echoed in my ears.

“Forget your perfect offerings. There’s a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

I still remember the day my father looked at me and spoke those words. It was three years ago; he was driving our beat-up Honda Pilot down the cracked city streets near our house in Washington, DC. I was sitting in the passenger seat, listening to his screed on the injustice of Bob Dylan receiving the Nobel Prize in literature. Dylan had become the first musician ever to do so, while Leonard Cohen’s romantic, heart wrenching, powerfully human expressions of divine beauty went unrecognized. How could Dylan’s songs be considered a greater contribution to literature than Cohen’s incisive commentary on the imperfection of man and his striving for love and grace?

Three years later, I found myself again discussing Cohen with my father, in the New York Jewish Museum’s new exhibit, “Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything.” Finally, this great artist was being recognized; much of the museum had been transformed into a temple of sorts to Cohen. And, in many ways, the temple was a fitting one: the ground floor of the museum had become a catacomb of darkened rooms, each showcasing a different artist’s audiovisual ode to Cohen. The result was an aura of somber, quiet listening and watching as Cohen’s mellifluous voice echoed in each chamber; the focus, of course, was on the man himself.

But, as The Guardian recently put it, the exhibit reveals Cohen only “through the eyes of others.” The effect can be a disjointed mess: some of the exhibits ranged from kitschy to off-putting and downright bizarre. Cohen – at least to me – was none of those things. The experience was a stark reminder that when viewing one artist through the lens of another, one risks a cloudy lens. It was difficult to see Cohen underneath the abstract shapes and rough animation of Kota Ezawa’s digital projection in “Cohen 21,” which was accompanied not by music or poetry but by the audio of the 1965 documentary Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen. It was difficult to hear Cohen in Christophe Chassol’s eerie, spectral “Cuba in Cohen,” which combined Cohen’s voice with several others reciting his poem “The Only Tourist in Havana.” And though the exhibit’s general creepiness was limited to the first floor, the comparatively bright second floor swung to the opposite extreme, presenting a cheap, commercialized version. Coming out of the elevator, one comes face to Tacita Dean’s “Ear on a Worm,” a three minute, thirty three second long film of a bird on a wire in homage to the Cohen piece of that name and length. This work has none of the depth, sorrow, and poetry of Cohen’s song. Where is the drunk in the midnight choir?

Perhaps the worst offender was art and design studio Daily Tous Les Jours’ “I Heard There was a Secret Chord,” which asked visitors to perch themselves on an octagonal bench and hum into one of the several dozen microphones hanging from the ceiling. In the background, a computer-generated simulation of hundreds of voices humming Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” with more voices added to the chorus depending on how many people are currently listening to the studio’s online radio station, asecretchord.com. Humming into the microphone causes the bench to vibrate, “closing the circuit” of kitschy, lifeless, robotic, repetitive meaninglessness. This was not Cohen, in all his depth, warmth, and romantic longing; this was not even human, which is perhaps what Cohen was above all else. This was corporate, computerized, and devoid of poetry.

The entire exhibit was saved, however, by the museum’s highest level. On the third floor I experienced “Listening to Leonard,” an hour-and-a-half long audio track comprised of covers of Cohen’s greatest hits by a range of contemporary artists. This was Cohen, in his own words and his own melodies; rather than experiencing him through another artist’s eyes, I was experiencing him through their voices. The songs played in a darkened room, with a single colored bar projected on one wall and dancing to the music, not assertive enough to detract from the auditory experience. Beanbag cushions were arranged on the floor, encouraging visitors to lie down on the ground, close their eyes, and be sublated into the music. Sufjan Stevens and The National delivered “Memories” in haunting fashion – not ghostly haunting, like the first floor exhibits, but humanly, passionately haunting. Ariane Moffatt and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra produced a full, emotional, heart-poundingly beautiful “Famous Blue Raincoat.” Dear Criminals covered “Anthem.” As I lay, motionless, next to my father, I was transported back three years. The museum fell away; the kitsch and the darkness and the commodification of beauty sank as I rose. Despite the museum’s flaws, I felt uplifted, consumed, raised by the music. Cohen’s words, sung by others, echoed in my ears.

“Forget your perfect offerings. There’s a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

//GIDON HALBFINGER is a senior in Columbia College and Politics Editor for The Current. He can be reached at [email protected].

Photo courtesy of https://thejewishmuseum.org/index.php/exhibitions/leonard-cohen-a-crack-in-everything.

Photo courtesy of https://thejewishmuseum.org/index.php/exhibitions/leonard-cohen-a-crack-in-everything.