//essays//

Spring 2017

Adding a Genre to the History of Art:

The Meme

Esther Moerdler

Fragments of a Marble Statue of the Diadoumenos (youth tying a fillet around his head), Copy of a work attributed to Polykleitos, ca. 69-96 BCE. Marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fragments of a Marble Statue of the Diadoumenos (youth tying a fillet around his head), Copy of a work attributed to Polykleitos, ca. 69-96 BCE. Marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If you are a Columbia undergraduate with a Facebook account, you probably get 20+ notifications a day from “columbia buy sell memes.” With 23,379 members, the group brings together the vast student body (and some unwelcome others) through combinations of text and image that poke fun at Columbia student culture. Columbia is not the only school with such a Facebook group: the trend started with “UC Berkeley Memes for Edgy Teens” and has spawned similar pages at campuses across the country. But the meme was not invented at Berkeley; in fact, it is much older than most people would expect.

Participants in today’s meme culture would probably surprised to learn that the term is actually borrowed from biology. In his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme” and defined it as any unit that is spread by imitation, analogous to how a virus spreads from one host organism to another. Merriam-Webster defines “meme” in a similar fashion, calling it “an idea, behavior, style, or usage that spreads from person to person within a culture.” The ever-reliable Urban Dictionary defines “meme” as “an idea, belief or belief system, or pattern of behavior that spreads throughout a culture either vertically by cultural inheritance (as by parents to children) or horizontally by cultural acquisition (as by peers, information media, and entertainment media).” By adopting these definitions of the “meme,” we can see that memes stem back much further than the the creation of these eponymous Facebook groups.

In essence, a meme is nothing more than the discernible transmission of an artistic idea from one culture to another via appropriation. Thus, some of the earliest memes in the Western tradition began with the Romans when they attempted to replicate Greek bronze originals. The Romans could not engineer the statues to the same caliber as the Greeks, so their statuary often included the addition of tree stumps or marble rods that would help the statue stay upright. These statues show the adaptations and appropriation of Greek culture into Roman society and can be reposed as the original memes. Put differently, they are adopted pieces of culture that have lost, at least according to Hito Steyerl, something of their original quality in their copying and appropriation.

Participants in today’s meme culture would probably surprised to learn that the term is actually borrowed from biology. In his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme” and defined it as any unit that is spread by imitation, analogous to how a virus spreads from one host organism to another. Merriam-Webster defines “meme” in a similar fashion, calling it “an idea, behavior, style, or usage that spreads from person to person within a culture.” The ever-reliable Urban Dictionary defines “meme” as “an idea, belief or belief system, or pattern of behavior that spreads throughout a culture either vertically by cultural inheritance (as by parents to children) or horizontally by cultural acquisition (as by peers, information media, and entertainment media).” By adopting these definitions of the “meme,” we can see that memes stem back much further than the the creation of these eponymous Facebook groups.

In essence, a meme is nothing more than the discernible transmission of an artistic idea from one culture to another via appropriation. Thus, some of the earliest memes in the Western tradition began with the Romans when they attempted to replicate Greek bronze originals. The Romans could not engineer the statues to the same caliber as the Greeks, so their statuary often included the addition of tree stumps or marble rods that would help the statue stay upright. These statues show the adaptations and appropriation of Greek culture into Roman society and can be reposed as the original memes. Put differently, they are adopted pieces of culture that have lost, at least according to Hito Steyerl, something of their original quality in their copying and appropriation.

Standing Ganesha, 12th century. Copper alloy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Standing Ganesha, 12th century. Copper alloy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Appropriation is not the only defining feature of meme culture; portability is a clearer example of cultural inheritance that more closely resembles our easily sharable memes. In antiquity, religious icons were kept in sites of worship until the time of a festival when they would be paraded through towns for people to see. For centuries in India, religious statues have been taken out of the temple, adorned with flowers, streamers, even jewelry, and paraded through the streets. Parading the icon allowed the work to be seen by hundreds, widely transmitting ideas about religion and worship. The adornments of both European icons and Indian bronze statuary are precursors to the text we see accompanying memes today, the almost religious image of pop culture being elevated by the text for the purpose of circulation and adoration.

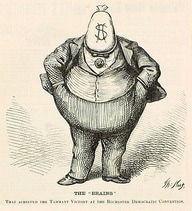

Boss Tweed depicted by Thomas Nast in a wood engraving published in Harper's Weekly, October 21, 1871.

Boss Tweed depicted by Thomas Nast in a wood engraving published in Harper's Weekly, October 21, 1871.

The invention of the printing press is the next big step in the direction of meme culture. Photographs and the like were used primarily for portraiture at this point, while illustrations were used within newspapers and pamphlets. After the invention, cartoons and illustrations could be widely circulated in print media, disseminating ideas about politicians, current events, and everyday life to an ever-growing audience. Take for example the now famous Live Free or Die cartoon published in Benjamin Franklin’s newspaper or the cartoons by Thomas Nast. Nast targeted William ‘Boss’ Tweed, a political boss in America in the 19th century, through mocking illustrations. These images are examples of ideas spread horizontally through cultural acquisition. Artists such as Nast were able to convey ideas about society even to those who were barely literate by taking well known symbols and images, and disseminating them with a twist.

The invention of the camera in 1814 marks the next major development in the history of the meme. As Walter Benjamin writes: “They [photographs] demand a specific kind of approach; free-floating contemplation is not appropriate to them. They stir the viewer; he feels challenged by them in a new way…for the first time, captions have become obligatory. And it is clear they have an altogether different character than the title of a painting.The directives which the captions give to those looking at pictures...where the meaning of each single picture appears to be prescribed by the sequence of all preceding ones.” With the invention of the photograph comes the need for a specific type of captioning. Captions can impact the understanding of a photograph in a way that few other things can. An image of a man riding a horse through a field, wearing an American flag jacket and carrying a large flag can be read multiple ways. Without a caption, the image might be read as one of the Fourth of July, but only captioning will inform the viewer that the image is one of a man who was involved in the armed takeover of an Oregon wildlife refuge earlier this year. The meaning of photographs are fluid, their supposed realism allowing for multiple interpretations. The caption functions as a means for tying down the meaning of the work according to the photographer. This is where the text that accompanies memes really begins to take form. Whereas before the photograph works would simply be accompanied by a descriptive title or adornments (such as a frame or floral wreaths in the case of Indian bronze statue adornment), the photograph’s supposed realism creates a requirement for greater description and interpretation.

The invention of the camera in 1814 marks the next major development in the history of the meme. As Walter Benjamin writes: “They [photographs] demand a specific kind of approach; free-floating contemplation is not appropriate to them. They stir the viewer; he feels challenged by them in a new way…for the first time, captions have become obligatory. And it is clear they have an altogether different character than the title of a painting.The directives which the captions give to those looking at pictures...where the meaning of each single picture appears to be prescribed by the sequence of all preceding ones.” With the invention of the photograph comes the need for a specific type of captioning. Captions can impact the understanding of a photograph in a way that few other things can. An image of a man riding a horse through a field, wearing an American flag jacket and carrying a large flag can be read multiple ways. Without a caption, the image might be read as one of the Fourth of July, but only captioning will inform the viewer that the image is one of a man who was involved in the armed takeover of an Oregon wildlife refuge earlier this year. The meaning of photographs are fluid, their supposed realism allowing for multiple interpretations. The caption functions as a means for tying down the meaning of the work according to the photographer. This is where the text that accompanies memes really begins to take form. Whereas before the photograph works would simply be accompanied by a descriptive title or adornments (such as a frame or floral wreaths in the case of Indian bronze statue adornment), the photograph’s supposed realism creates a requirement for greater description and interpretation.

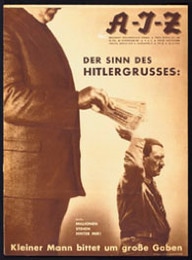

The Meaning of the Hitler Salute: Little Man Asks for Big Gifts, 1932

© 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

The Meaning of the Hitler Salute: Little Man Asks for Big Gifts, 1932

© 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

By the mid-twentieth century, photographs had taken on a life of their own. No longer only used for portraiture or documentary, they were spliced and overlaid to create montages and seamless collages conveying political messages. Take, for example, the work of Dada photomontagist John Heartfield, who produced photomontages critical of the rise of Nazism and published them in magazines. In one of his magazine covers, Heartfield seamlessly combines an image of the looming, cut-off figure of a man handing over a wad of cash, with a small image of a saluting Hitler. He accompanies the image with a caption that reads, “The meaning of Hitler, Little man asks for big gifts.” Heartfield’s message is clear: Hitler is corrupt. What’s more, he calls out Hitler’s corruption through one the most popular forms of media of the time, the newspaper.

The invention of the Internet marks the next goal-post in the history of today’s memes. As we can see, the meme is nothing new to history, it has always been a matter of appropriated and copied images that serve as pedagogical tools within a culture. With the advent of the Internet, a newer and faster means of replication and dissemination made the meme something that could be produced by anyone, not just an artist or craftsman.

The invention of the Internet brought with it the creation of the “poor image.” Writer and filmmaker Hito Steyerl explained the poor image as “a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard... The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its filenames are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self.” These poor images are essential to the production of today’s memes. The compressed, screen-shotted, over-edited, cropped, overlaid, captioned images add new layers of meaning to everything from medieval paintings to Ru-Paul’s Drag Race and everything in between.

There’s something human about the desire to personalize and transmit elements of culture, and memes are just another manifestation of this need. Dawkins would argue that this is an essential characteristic of all living things, down to microscopic viruses. Beginning in ancient Rome, and likely even earlier, items of cultural production were appropriated as “bastard copies” of the original. These sculptures today are often the best link we have to the originals, though they tell us little of the original work’s context. The inventions of the printing press, the camera, and the Internet made replication and dissemination of images far more accessible to the common-folk. Though memes might seem like a new phenomenon and a “low culture” mode of production, it has its roots planted in the distant past, deep within the production of “high culture.”

The invention of the Internet marks the next goal-post in the history of today’s memes. As we can see, the meme is nothing new to history, it has always been a matter of appropriated and copied images that serve as pedagogical tools within a culture. With the advent of the Internet, a newer and faster means of replication and dissemination made the meme something that could be produced by anyone, not just an artist or craftsman.

The invention of the Internet brought with it the creation of the “poor image.” Writer and filmmaker Hito Steyerl explained the poor image as “a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard... The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its filenames are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self.” These poor images are essential to the production of today’s memes. The compressed, screen-shotted, over-edited, cropped, overlaid, captioned images add new layers of meaning to everything from medieval paintings to Ru-Paul’s Drag Race and everything in between.

There’s something human about the desire to personalize and transmit elements of culture, and memes are just another manifestation of this need. Dawkins would argue that this is an essential characteristic of all living things, down to microscopic viruses. Beginning in ancient Rome, and likely even earlier, items of cultural production were appropriated as “bastard copies” of the original. These sculptures today are often the best link we have to the originals, though they tell us little of the original work’s context. The inventions of the printing press, the camera, and the Internet made replication and dissemination of images far more accessible to the common-folk. Though memes might seem like a new phenomenon and a “low culture” mode of production, it has its roots planted in the distant past, deep within the production of “high culture.”

//ESTHER MOERDLER is a senior in Barnard College. She can be reached at [email protected]