// essays //

Fall 2016

Trigger Happy

Waging a Rhetorical War on Women at a Women’s College

Hannah Vaitsblit

Over four years ago, Barnard College enchanted me with an Accepted Students Day panel—an initial introduction to the school’s vibrant PR machine that I would come to know (and hate) intimately. The students on the panel—accomplished, articulate, and confident Barnard women—wooed the crowd of eager prospective students by identifying the chronic problem women suffer from, whether in the classroom or the boardroom: “excessive apologizing.”

Eager to become like these women—self-aware and unapologetic—my college decision was swayed by the prospect of becoming that mythical “bold, beautiful Barnard” woman I had come to admire through the mystically euphoric reminisces of alumnae in my community. Barnard seemed an irresistible—and almost inevitable—choice in a world framed as fundamentally at odds with the assertive, modern, erudite woman. And so, not entirely aware of the extent of the cultural radicalism I was to encounter upon matriculation, I chose to attend Barnard over the significantly more prestigious University of Chicago (which has since become renowned—or infamous—for its own administrative resistance against the cultural suppression of free speech by way of trigger warnings).

As a senior reflecting upon my tenure at Barnard, I unfortunately still cannot say with certainty that I made the right choice. I have come to find that the culture of “excessive apologizing” is very much alive at Barnard and pervasive even—perhaps especially—in the most radical feminist hamlets. Barnard has empowered me as a woman on occasion and has opened my mind in a few rare instances, but it has also exposed the logical inconsistency of the paradoxical feminism that thrives within its walls.

While I hesitate to give this frivolous platform any more screen time, a basic examination of the public Facebook group Overheard @ Barnard illustrates this perverse doublethink, probably better than anything else. As an active follower—and, regrettably, an occasional participant—of this group, I pay close attention to the posts following “cw” (content warning) and “tw” (trigger warning). Recently, I have noticed a recurring trend: the use of trigger/content warnings to call attention to--I suppose, triggering and vile—sex, genitals, genitalia (use your imagination for the rest of the list). The warnings are attached to posts that range from trivial messages about sexile to disturbing fantasies involving Joe Biden; sometimes, there is actually serious anatomical discourse involved.

These tokens resemble a TV or film content warning, except there’s no real way to press pause; by the time you’ve read the warning, your eyes have probably scanned over the potentially funny or scandalous or crass climax of the show, the subject “overheard” in question. Unlike the Federal Communications Commission’s television content rating system or the Motion Picture Association of America’s rating system, these particular preemptive insertions do not exist within a logical framework nor do they mandate justification. Big screen ratings are not flawless, especially when they warn against nudity in an industry where it is three times more likely to be female. But these trigger warnings amount to an even more sinister slogan: an explicit apology in advance for what turns out to mostly be a discussion of the female body.

A debate of the merits and demerits of trigger/content warnings is not what is at stake in this particular usage of these devices. Rather, it is the dissonance between this manufactured online sensitivity and the concurrent destigmatization that has taken hold of both our activist community and the broader student population (not to mention the general population). A content warning preceding a discussion about female body parts—no matter how trite—seems to be a pernicious version of that exact excessive apologizing that Barnard students had once purportedly campaigned against.

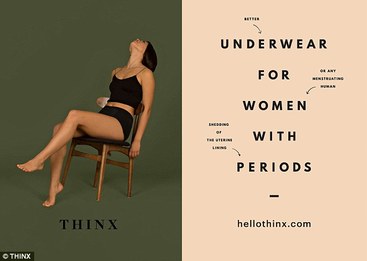

Just a year ago, a version of this debate went viral—or at least captured New York City, which is close enough to virality. Thinx, the hi-tech menstrual underwear developer, entered into a battle with the New York MTA’s advertising partner over the appropriateness of the company’s ads, promoting the technologically disruptive product. These ads had no trigger warnings on them,perhaps because copywriters have little patience for this kind of college coddling, or maybe because “breaking the period taboo"—a stated goal of the ad campaign—requires breaking with the beloved content warning once and for all. The clever and tasteful directness of the campaign puts it all on the table, aiming to destigmatize and encourage conversation surrounding this very human phenomenon experienced by half the population.

I don’t agree with every issue position that Thinx takes, but I smile every time I pass by the company’s ads on the Subway. On a base level, because they are witty and aesthetic, but moreover, because they make me slightly uncomfortable, and that’s the point. Frankly, these ads are not any more offensive than those advertising breast augmentation in order to “overcome your bikini fears.”

My mother once told me that back in the Soviet Union, nobody talked openly about lifecycle changes. A young girl didn’t know about periods until she literally started bleeding, probably fearing for her life. While there is something to be said for privacy—and the value of indiscriminately broadcasting bodily functions in general can certainly be debated—the hypocrisy of advocating for destigmatization while simultaneously perpetuating that same stigmatization cannot be logically justified. Overheard @ Barnard is a hotbed of women’s sexual liberation, or some weird post-modern, meme-ified version of it. The use of trigger warnings preceding posts about the female body or sexuality reflects a kind of internal struggle on the part of the Overheard community—a clash of priorities in which the fetishized trigger warning very often defeats destigmatization of the female body in a fateful battle of contradictions. Comments like “female is such a gross word” perpetuate the full-scale demonization of womanhood and activate the apologetic culture wafting its way from the bottom up. If New York can handle some period underwear, Barnard students should certainly be able to deal with the female body—without apology.

It seems Overheard is not the only place at Barnard where the woman is under attack. Several weeks ago, Barnard held a post-election panel for Barnard students featuring Barnard professors. When it came to the Q&A portion, the moderator, a woman, called on an audience member sitting in the front row:

“The woman—uh…person—in the red shirt.”

A friend smiled giddily and whispered to me something along the lines of: “Oops, we don’t use that word anymore!” and I sat dumbstruck, thinking that if it had been me, I would have sarcastically retorted, “It’s OK, you can say 'woman.'"

It’s not that I don’t understand the complexity of the issues surrounding gender on our campus, but the fear that overtook the moderator’s face when she mistakenly uttered a non-neutral noun was equally frightening to the observant onlooker. On the institutional scale, Barnard generally preempts this mistake by incorporating the “preferred gender pronoun” exercise into new student orientation (in fact, one of the first questions hurled at me when I arrived on campus was “what’s your PGP?!”). While the college pursues its normative campaign, Overheard regularly reinforces the gravity of the misgendering mistake. A recent post musing “I can’t believe I just misgendered myself,” summarizes the absurdity of the gendering witch-hunt, extending to the point of self-censorship.

That misgendering could be such a crime is unfortunate, because there is a lot to be learned from the phenomenon. It is possible to get to know an individual without being privy to gender or sexual identity, so much the more so without disparaging that identity once it is known. But it seems that, besides militant promotion of obligatory gender-identity disclaimers, demonization of the woman is back in vogue.

Barnard—yes, still referred to as a women’s college last time I checked—at both the informal and formal levels, has excluded, marginalized, and ostracized the woman out of fear of accusatory activists. In an environment where the majority population are, in fact, women, the identity so associated with the institution’s purpose has become scornful.

Perhaps the context makes this possible. In an environment so ostensibly nurturing—a “premier liberal arts college for the brightest young women around”—the luxury of celebrated womanhood is taken for granted. We’ve become so comfortable with these casualties, forgetting that every rhetorical move we make contributes to the creation of a culture. In the real world, these apologies will be taken at face value, not as arguments, but rather as surrender. Barnard has historically resisted surrender for quite some time—its continued independent existence as one of the few remaining women’s colleges is a testament to that. Barnard’s students would be wise to follow the institution’s lead and shed apology out of style, no disclaimers necessary.

Eager to become like these women—self-aware and unapologetic—my college decision was swayed by the prospect of becoming that mythical “bold, beautiful Barnard” woman I had come to admire through the mystically euphoric reminisces of alumnae in my community. Barnard seemed an irresistible—and almost inevitable—choice in a world framed as fundamentally at odds with the assertive, modern, erudite woman. And so, not entirely aware of the extent of the cultural radicalism I was to encounter upon matriculation, I chose to attend Barnard over the significantly more prestigious University of Chicago (which has since become renowned—or infamous—for its own administrative resistance against the cultural suppression of free speech by way of trigger warnings).

As a senior reflecting upon my tenure at Barnard, I unfortunately still cannot say with certainty that I made the right choice. I have come to find that the culture of “excessive apologizing” is very much alive at Barnard and pervasive even—perhaps especially—in the most radical feminist hamlets. Barnard has empowered me as a woman on occasion and has opened my mind in a few rare instances, but it has also exposed the logical inconsistency of the paradoxical feminism that thrives within its walls.

While I hesitate to give this frivolous platform any more screen time, a basic examination of the public Facebook group Overheard @ Barnard illustrates this perverse doublethink, probably better than anything else. As an active follower—and, regrettably, an occasional participant—of this group, I pay close attention to the posts following “cw” (content warning) and “tw” (trigger warning). Recently, I have noticed a recurring trend: the use of trigger/content warnings to call attention to--I suppose, triggering and vile—sex, genitals, genitalia (use your imagination for the rest of the list). The warnings are attached to posts that range from trivial messages about sexile to disturbing fantasies involving Joe Biden; sometimes, there is actually serious anatomical discourse involved.

These tokens resemble a TV or film content warning, except there’s no real way to press pause; by the time you’ve read the warning, your eyes have probably scanned over the potentially funny or scandalous or crass climax of the show, the subject “overheard” in question. Unlike the Federal Communications Commission’s television content rating system or the Motion Picture Association of America’s rating system, these particular preemptive insertions do not exist within a logical framework nor do they mandate justification. Big screen ratings are not flawless, especially when they warn against nudity in an industry where it is three times more likely to be female. But these trigger warnings amount to an even more sinister slogan: an explicit apology in advance for what turns out to mostly be a discussion of the female body.

A debate of the merits and demerits of trigger/content warnings is not what is at stake in this particular usage of these devices. Rather, it is the dissonance between this manufactured online sensitivity and the concurrent destigmatization that has taken hold of both our activist community and the broader student population (not to mention the general population). A content warning preceding a discussion about female body parts—no matter how trite—seems to be a pernicious version of that exact excessive apologizing that Barnard students had once purportedly campaigned against.

Just a year ago, a version of this debate went viral—or at least captured New York City, which is close enough to virality. Thinx, the hi-tech menstrual underwear developer, entered into a battle with the New York MTA’s advertising partner over the appropriateness of the company’s ads, promoting the technologically disruptive product. These ads had no trigger warnings on them,perhaps because copywriters have little patience for this kind of college coddling, or maybe because “breaking the period taboo"—a stated goal of the ad campaign—requires breaking with the beloved content warning once and for all. The clever and tasteful directness of the campaign puts it all on the table, aiming to destigmatize and encourage conversation surrounding this very human phenomenon experienced by half the population.

I don’t agree with every issue position that Thinx takes, but I smile every time I pass by the company’s ads on the Subway. On a base level, because they are witty and aesthetic, but moreover, because they make me slightly uncomfortable, and that’s the point. Frankly, these ads are not any more offensive than those advertising breast augmentation in order to “overcome your bikini fears.”

My mother once told me that back in the Soviet Union, nobody talked openly about lifecycle changes. A young girl didn’t know about periods until she literally started bleeding, probably fearing for her life. While there is something to be said for privacy—and the value of indiscriminately broadcasting bodily functions in general can certainly be debated—the hypocrisy of advocating for destigmatization while simultaneously perpetuating that same stigmatization cannot be logically justified. Overheard @ Barnard is a hotbed of women’s sexual liberation, or some weird post-modern, meme-ified version of it. The use of trigger warnings preceding posts about the female body or sexuality reflects a kind of internal struggle on the part of the Overheard community—a clash of priorities in which the fetishized trigger warning very often defeats destigmatization of the female body in a fateful battle of contradictions. Comments like “female is such a gross word” perpetuate the full-scale demonization of womanhood and activate the apologetic culture wafting its way from the bottom up. If New York can handle some period underwear, Barnard students should certainly be able to deal with the female body—without apology.

It seems Overheard is not the only place at Barnard where the woman is under attack. Several weeks ago, Barnard held a post-election panel for Barnard students featuring Barnard professors. When it came to the Q&A portion, the moderator, a woman, called on an audience member sitting in the front row:

“The woman—uh…person—in the red shirt.”

A friend smiled giddily and whispered to me something along the lines of: “Oops, we don’t use that word anymore!” and I sat dumbstruck, thinking that if it had been me, I would have sarcastically retorted, “It’s OK, you can say 'woman.'"

It’s not that I don’t understand the complexity of the issues surrounding gender on our campus, but the fear that overtook the moderator’s face when she mistakenly uttered a non-neutral noun was equally frightening to the observant onlooker. On the institutional scale, Barnard generally preempts this mistake by incorporating the “preferred gender pronoun” exercise into new student orientation (in fact, one of the first questions hurled at me when I arrived on campus was “what’s your PGP?!”). While the college pursues its normative campaign, Overheard regularly reinforces the gravity of the misgendering mistake. A recent post musing “I can’t believe I just misgendered myself,” summarizes the absurdity of the gendering witch-hunt, extending to the point of self-censorship.

That misgendering could be such a crime is unfortunate, because there is a lot to be learned from the phenomenon. It is possible to get to know an individual without being privy to gender or sexual identity, so much the more so without disparaging that identity once it is known. But it seems that, besides militant promotion of obligatory gender-identity disclaimers, demonization of the woman is back in vogue.

Barnard—yes, still referred to as a women’s college last time I checked—at both the informal and formal levels, has excluded, marginalized, and ostracized the woman out of fear of accusatory activists. In an environment where the majority population are, in fact, women, the identity so associated with the institution’s purpose has become scornful.

Perhaps the context makes this possible. In an environment so ostensibly nurturing—a “premier liberal arts college for the brightest young women around”—the luxury of celebrated womanhood is taken for granted. We’ve become so comfortable with these casualties, forgetting that every rhetorical move we make contributes to the creation of a culture. In the real world, these apologies will be taken at face value, not as arguments, but rather as surrender. Barnard has historically resisted surrender for quite some time—its continued independent existence as one of the few remaining women’s colleges is a testament to that. Barnard’s students would be wise to follow the institution’s lead and shed apology out of style, no disclaimers necessary.

// HANNAH VAITSBLIT is a senior in Barnard College and is Senior Editor of The Current. She can be reached at [email protected]. Photo courtesy of Thinx.