//literary and arts//

Spring 2019

Spring 2019

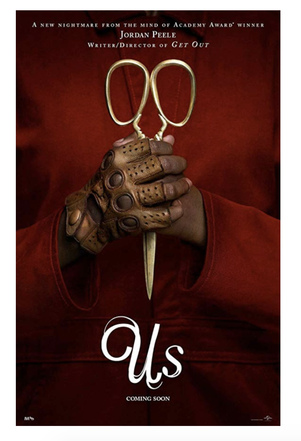

What's Beneath the Ground in Jordan Peele's US?

Harry Ottensoser

Jordan Peele's “US” doesn’t make any sense. Clearly, that didn’t matter to him. Should it matter to us?

US is the second film from Peele, the newly crowned king of horror. US successfully inserted itself directly into the cultural conversation months before its release, when all critics had to discuss was a short teaser and an eerie poster. Since hitting theaters, the film and its meaning have been the subject of endless reviews, think-pieces, Reddit theories. Each of these reactions aims to pick up the pieces left by the director and determine the film’s subtext, asking what, exactly, Peele is trying to say in the film. All films seek to spark interest; US, however, was designed to ignite a specific kind of conversation, often sacrificing narrative logic in favor of laying the groundwork for the movie’s existence beyond the two hours of theater time that define the lifespan of a traditional film.

This film is uniquely of our time. It embraces its relationship with an internet audience, and directly feeds into their responses, clearly aware that internet critics will help bring to life and validate the film’s wildest ideas, in addition to controlling its popularity and general reception. Much of this sentiment can be exposed through the narrative sacrifices that the film makes—meaning the plot-holes it engenders, or the parts of the film that, from the perspective of the narrative, simply don’t hang together—and the theories and ideas that these sacrifices enable.

One of the most discussed moments in the film arrives when the Wilson family, the protagonists, finally come face to face with their doppelgängers, who (spoiler alert!) are trying to murder them. When Adelaide, the Wilson mother, asks the doppelgängers to identify themselves, Red (the mother-doppelgänger) responds cryptically, and, in retrospect, nonsensically, “We’re Americans.” Many critics have been quick to point out this line’s social implications, and hypothesize that Peele is criticizing the American elite’s neglect of the country’s poorer communities. While this line successfully transmits this idea,, it ultimately makes little sense in context, and the film’s plot never satisfyingly refers back to it. Though there are possible ways to explain this line’s presence, none are truly satisfying—beyond the idea that it was sure to evoke an audience response.

Similarly, the costumes that the Tethered—the doppelgängers—wear, which are matching red jumpsuits and single fingerless leather gloves, are engineered to be both frightening and iconic, but don’t necessarily point to anything more substantive. The film offers no indication as to why the Tethered would dress like this, or how they got or created any of their clothing in the first place, since (again, spoiler alert!) they’ve been forced to live underground. Peele’s decision to not even attempt to offer an explanation demonstrates his desire to create a memorable and replicable iconography with his film, even when it defies any sense of logical clarity. Sure, most horror films in the pop culture canon have been defined by iconic pieces of clothing. Freddy Krueger’s hat and sweater in A Nightmare on Elm Street, Michael Myers’ white mask and prison jumpsuit in Halloween, and Jason Voorhees’ hockey mask in Friday the 13th are all examples of iconic horror movie costumes. The difference is that those films made somewhat of an effort to explain these costume choices. Freddy was a murdered janitor, Myers had just escaped a mental institution, and Jason took his mask from the body of one of his victims—all three costumes are based in narrative logic to them. US, on the other hand, crafts a striking visual world without any narrative explanation, leaving images that will surely be replicated nationwide this Halloween, but without any clear reasons behind them.

Many of the film’s other choices can be attributed to its prioritization of the meta-conversation over narrative logic. The Tethereds’ weapon of choice, scissors, has inspired its own theories. Critics have argued that scissors, composed of two pieces that must always move in unison, reflect the twisted relationship between the Tethered and their human counterparts (since the Tethered are, bizarrely, physically “tethered” to the actions of their human doppelgängers, forced to perform the actions their above-ground pairs perform). The bunnies that roam the tunnels where the Tethered live make for a frighteningly eerie visual, but no explanation is given as to how they got there and why they are the Tethereds’ only food source. The aforementioned leather glove, worn on the Tethereds’ left hands, has sparked theories that connect it the glove worn by Michael Jackson, perhaps alluding to an idea of a dual identity that can be derived from the controversial pop icon’s complicated biography. All sorts of symbols and motifs are littered throughout the film, and, like these, rarely make narrative sense.

* * *

Peele understands the way the internet interacts with pop culture. His horror film career comes after years as one half of the comedy duo “Key and Peele,” whose videos often achieved viral fame and benefited greatly from their relationship to the internet. His past experience informed his feature film debut, Get Out, which was laced with its own symbolism. But Peele seems to have leaned into this concept more deeply with US, engineering the film around the symbolism and ideas he wanted people to talk about. As a result, the film falters as a piece of clear-cut storytelling, and its ideas often fail to stand on their own, lacking the narrative logic they need to be support their own weight. The film soars, however, in the hours, days, and weeks after it’s watched, as the viewer reassembles the pieces laid out by Peele and uncovers the ideas and clues they missed the first time around, drawing their own connections and meanings from the film’s many ambiguities. While this project is certainly satisfying, and creates more viewer engagement than most films, US’s attempt to inspire a lasting impact ultimately fails, as the story beneath it crumbles in the face of an examination of its narrative coherence.

US is the second film from Peele, the newly crowned king of horror. US successfully inserted itself directly into the cultural conversation months before its release, when all critics had to discuss was a short teaser and an eerie poster. Since hitting theaters, the film and its meaning have been the subject of endless reviews, think-pieces, Reddit theories. Each of these reactions aims to pick up the pieces left by the director and determine the film’s subtext, asking what, exactly, Peele is trying to say in the film. All films seek to spark interest; US, however, was designed to ignite a specific kind of conversation, often sacrificing narrative logic in favor of laying the groundwork for the movie’s existence beyond the two hours of theater time that define the lifespan of a traditional film.

This film is uniquely of our time. It embraces its relationship with an internet audience, and directly feeds into their responses, clearly aware that internet critics will help bring to life and validate the film’s wildest ideas, in addition to controlling its popularity and general reception. Much of this sentiment can be exposed through the narrative sacrifices that the film makes—meaning the plot-holes it engenders, or the parts of the film that, from the perspective of the narrative, simply don’t hang together—and the theories and ideas that these sacrifices enable.

One of the most discussed moments in the film arrives when the Wilson family, the protagonists, finally come face to face with their doppelgängers, who (spoiler alert!) are trying to murder them. When Adelaide, the Wilson mother, asks the doppelgängers to identify themselves, Red (the mother-doppelgänger) responds cryptically, and, in retrospect, nonsensically, “We’re Americans.” Many critics have been quick to point out this line’s social implications, and hypothesize that Peele is criticizing the American elite’s neglect of the country’s poorer communities. While this line successfully transmits this idea,, it ultimately makes little sense in context, and the film’s plot never satisfyingly refers back to it. Though there are possible ways to explain this line’s presence, none are truly satisfying—beyond the idea that it was sure to evoke an audience response.

Similarly, the costumes that the Tethered—the doppelgängers—wear, which are matching red jumpsuits and single fingerless leather gloves, are engineered to be both frightening and iconic, but don’t necessarily point to anything more substantive. The film offers no indication as to why the Tethered would dress like this, or how they got or created any of their clothing in the first place, since (again, spoiler alert!) they’ve been forced to live underground. Peele’s decision to not even attempt to offer an explanation demonstrates his desire to create a memorable and replicable iconography with his film, even when it defies any sense of logical clarity. Sure, most horror films in the pop culture canon have been defined by iconic pieces of clothing. Freddy Krueger’s hat and sweater in A Nightmare on Elm Street, Michael Myers’ white mask and prison jumpsuit in Halloween, and Jason Voorhees’ hockey mask in Friday the 13th are all examples of iconic horror movie costumes. The difference is that those films made somewhat of an effort to explain these costume choices. Freddy was a murdered janitor, Myers had just escaped a mental institution, and Jason took his mask from the body of one of his victims—all three costumes are based in narrative logic to them. US, on the other hand, crafts a striking visual world without any narrative explanation, leaving images that will surely be replicated nationwide this Halloween, but without any clear reasons behind them.

Many of the film’s other choices can be attributed to its prioritization of the meta-conversation over narrative logic. The Tethereds’ weapon of choice, scissors, has inspired its own theories. Critics have argued that scissors, composed of two pieces that must always move in unison, reflect the twisted relationship between the Tethered and their human counterparts (since the Tethered are, bizarrely, physically “tethered” to the actions of their human doppelgängers, forced to perform the actions their above-ground pairs perform). The bunnies that roam the tunnels where the Tethered live make for a frighteningly eerie visual, but no explanation is given as to how they got there and why they are the Tethereds’ only food source. The aforementioned leather glove, worn on the Tethereds’ left hands, has sparked theories that connect it the glove worn by Michael Jackson, perhaps alluding to an idea of a dual identity that can be derived from the controversial pop icon’s complicated biography. All sorts of symbols and motifs are littered throughout the film, and, like these, rarely make narrative sense.

* * *

Peele understands the way the internet interacts with pop culture. His horror film career comes after years as one half of the comedy duo “Key and Peele,” whose videos often achieved viral fame and benefited greatly from their relationship to the internet. His past experience informed his feature film debut, Get Out, which was laced with its own symbolism. But Peele seems to have leaned into this concept more deeply with US, engineering the film around the symbolism and ideas he wanted people to talk about. As a result, the film falters as a piece of clear-cut storytelling, and its ideas often fail to stand on their own, lacking the narrative logic they need to be support their own weight. The film soars, however, in the hours, days, and weeks after it’s watched, as the viewer reassembles the pieces laid out by Peele and uncovers the ideas and clues they missed the first time around, drawing their own connections and meanings from the film’s many ambiguities. While this project is certainly satisfying, and creates more viewer engagement than most films, US’s attempt to inspire a lasting impact ultimately fails, as the story beneath it crumbles in the face of an examination of its narrative coherence.

//HARRY OTTENSOSER is a sophomore in Columbia College. He can be reached at ho2262@ columbia.edu.

Photo courtesy of https://www.amazon.com/POSTER-ORIGINAL-Advance-JORDAN-LUPITA/dp/B07MMZHJNK.

Photo courtesy of https://www.amazon.com/POSTER-ORIGINAL-Advance-JORDAN-LUPITA/dp/B07MMZHJNK.