//politics//

Spring 2019

Spring 2019

Mr. Guggenheim, Take Down This Donor: When Activism and Art Collide

Yaira Kobrin

For some, a museum is nothing more than a place to visit on a rainy day, on a middle school trip, maybe on a date. For others, it’s a building whose glittering donor wall reeks of oppression, addiction, or worse—and it’s time to hold some of these donors accountable.

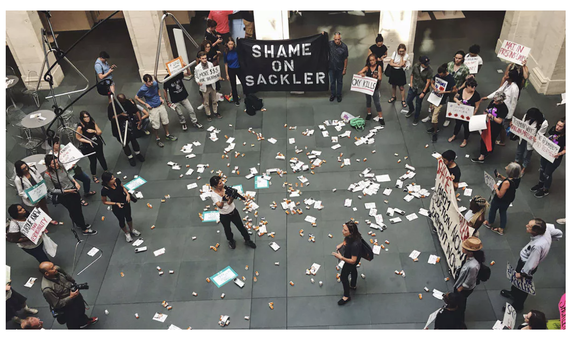

On February 9th, 2019, the Guggenheim lobby was littered with empty pill bottles and several people sprawled out across the floor. Above them, lining the museum’s iconic spiral interior, others held red banners which proclaimed, in large black letters, “400,000 DEAD,” “SHAME ON SACKLER,” and “TAKE DOWN THEIR NAME.” Mock prescriptions for OxyContin fluttered down from the ceiling, landing at the feet of Nan Goldin—the photographer and activist who founded P.A.I.N., the group that had organized the protest via Instagram. To the uninformed, the scene may have looked like an elaborate piece of performance art—not unexpected for a museum famous for its elaborate and provocative installations. In this case, it was something altogether different: an outside group, invading the museum to wage an ideological battle.

Welcome to a new form of protest: the museums are the battlefield, and the war—though not exclusively—is about who gets to empower art.

Goldin is a recovering OxyContin addict. She has spoken and written openly about her struggles, and founded P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) in order to protest the Sackler family. The Sacklers own Purdue Pharma, the company that produces and markets OxyContin. P.A.I.N.’s mission statement, in no uncertain terms, decries the Sackler family’s wealth as “blood money” and calls for “all… institutions worldwide [to] remove Sackler signage and publicly refuse future funding from the Sacklers.” P.A.I.N., at least on the surface, seems no different than other movements which call for organizations or individuals to refuse “dirty money.”

But this story is different. Nan Goldin is as much an artist as she is an activist. In fact, some of her works hang in the Guggenheim’s galleries. And she’s taken her war against the Sackler family not to the Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at NYU Langone Health, nor to the Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology at Columbia, nor to the many other Sackler-named institutions scattered across the United States, but rather to the Guggenheim, which houses the Sackler Center for Arts Education, and to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose famous Temple of Dendur is housed in the Sackler Wing. The Sackler family name is on the door of countless institutions, yet Goldin, and P.A.I.N., have chosen museums as the sites of their protests. For Goldin, the Sacklers’ involvement in museums is the worst offense of all—the association of their “dirty money” with the art world is somehow more despicable than an association with any other industry.

Goldin and P.A.I.N are not alone. On March 22nd, 2019, the activist group Decolonize This Place kicked off their “Nine Weeks of Art and Action” at the Whitney, an art museum less than two miles from the Guggenheim. Like P.A.I.N., Decolonize This Place primarily protests museums and their donors, and is calling for the removal of Warren Kanders. Kanders serves as the Vice Chairman of the Whitney and also owns Safariland, a manufacturer of military and law enforcement equipment, including the tear gas being used at the U.S.-Mexico border. In the nine weeks leading up to the Whitney’s biennial celebration, Decolonize This Place has chosen to protest every Friday night, blocking the art of the Whitney with colorful banners of their own. This protest, too, seems at home within the museum’s aesthetic; the banners of the protestors evoke images from the Whitney’s exhibition aptly titled “An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections From the Whitney’s Collection, 2014-2017,” which ran from August 2017 until August 2018. Decolonize This Place have not taken their protests to the Winston Churchill Foundation, where Kanders is also a board member, nor have they gone to the NYPD, who also use Safariland-made gear (although some signs at their protests are dedicated to this issue as well). Instead, Decolonize This Place, like Goldin and P.A.I.N., have made the museum their battleground, decrying the influence that Kanders and, in P.A.I.N.’s case, the Sackler family, have on the museum specifically. Why?

Protests like these call upon a long tradition of criticism, one which challenges the notion that museums are zones of neutrality. This tradition is most coherently reflected throughout the canon of the philosophy of art, in which , one after another, philosophers dispute what, exactly, qualifies as art. Arthur Danto, former Columbia professor and a philosopher of art, explains in his essay, “The Artworld,” that over time, different theories of art have dictated what art is—and, in turn, dictated which works make it into museums.

A museum, by its very nature, declares “this is art.” The works that hang in its galleries, line its halls, and fill its sculpture gardens, are all “art;” the pieces left on the outside, excluded from the hallowed halls of the museum, as Danto points out, are consequently not art. This has powerful ramifications: with the ability to decide what is and is not art comes, as Danto argues, the ability to decide whose voice matters, and whose does not. In his essay “The Artworld Revisited,” Danto argues for a new theory of art which would be practically all-encompassing, in an attempt to create space for as many voices within the artworld as possible. We have yet to see the realization of such a theory—no museum, so far, has seemingly been able to accept such a vast and expansive definition of art. Instead, museums still operate with narrow definitions and act as the all-powerful judges of what counts as art and what does not, a fact with stunning implications.

Organizations such as Goldin’s P.A.I.N. and Decolonize This Place are far from the first to recognize the impact of museums, or to use them as a battleground to combat broad issues. In 1985, a group of women formed the Guerrilla Girls, an activist group dedicated to fighting gender inequality in the art world. The impetus of their formation? An exhibit at the MoMA, titled “An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture,” which claimed to showcase the most significant contemporary artworks to-date. The exhibit featured 148 male artists and only 13 females, with 0 artists of color represented. Though the Guerrilla Girls have gone on to protest inequality in a variety of spheres, one of their primary goals continues to be fighting for equal representation in museum galleries. To be included in a gallery, they protest, is more than simply seeing your paintings on the wall; instead, it is a powerful statement about whether your work is—or is not—art, and therefore whether or not your voice and vision matter in contemporary culture.

The reasons that Goldin, P.A.I.N., Decolonize This Place and the Guerrilla Girls have chosen to protest at museums all center around the power of the museum, and the questions of who gets to be included in the cultural conversation. These arguments should sound familiar to Columbia students, who are well-versed in conversations about the power of being included in the canon. Few professors of the Core curriculum will finish a semester or two of class without at least some time dedicated to a discussion on the power and problems of the canon. Over the years, the syllabi of all Core classes have evolved to include more minority artists, writers, and thinkers. The canon, for all intents and purposes, is a museum: if you’re in, you and your work matter; if you’re not, you and your work do not.

This power—the ability to decide what works should or shouldn’t endure—is one that many of these institutions often abuse. But it’s also one that they use, in incredibly powerful ways. On February 3rd, 2017, less than ten days after President Trump issued a travel ban on Iran, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, Syria, North Korea, and Venezuela, the MoMA pulled works by Picasso and Matisse (among other Western artists) off the walls of one of their galleries, replacing them instead with work from artists born in the countries blocked by the travel ban. This wasn’t a subtle act of protest; next to each of the replaced artworks was hung a plaque that clearly explained that the artists of these works were from the banned countries, and that their work had been re-hung by the MoMA “to affirm the ideals of welcome and freedom as vital to this Museum as they are to the United States.”

The MoMA isn’t the only museum to have created exhibits which serve as purposeful acts of protest. Two weeks later, on February 16th, 2017, the Davis Museum in Wellesley, MA protested the travel ban by removing all works of art created by artists from the banned nations, showcasing, through the blank spaces in various galleries, these artists’ importance. And museums don’t just protest President Trump or the travel ban. The Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art pushed boundaries with its “Heavenly Bodies” theme earlier this year, which forced viewers to scrutinize Catholic vestments at a time when the Catholic Church itself is under similar scrutiny.

Of course Nan Goldin took her fight with the Sackler Family to the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Of course Decolonize This Place went to the Whitney over the Winston Churchill Foundation. Because museums monopolize, for better and for worse, the art world, directly impacting the way we see art and artists, deciding which works we’ll remember and which we’ll forget, which we’ll have access to and which will gather dust in a basement somewhere, and ultimately whose voices we’ll listen to and whose will be silenced forever.

There is an interesting post-script to this story, which is still being written. In March, around a month after Nan Goldin’s protest at the Guggenheim, the Tate Museum in London and the Guggenheim Museum each announced separately that they would no longer be accepting donations from the Sackler family. The Sackler Trust, the charity arm of the Sackler family, issued a statement saying that they would be halting donations in the United Kingdom. As new allegations swirl, and the number of states in the U.S. suing Purdue Pharma continues to climb (the current count is around three dozen), the work that Goldin has done is suddenly highlighted, even more, as the ultimate success story. At the protest at the Whitney by Decolonize This Place, which kicked off their nine weeks of protests, a member of P.A.I.N. took the microphone and, smiling, assured protesters that “direct actions work.” The theme of that night, according to ArtNews, was one sentence, repeated by many of the activists present: “This is only the beginning.”

On February 9th, 2019, the Guggenheim lobby was littered with empty pill bottles and several people sprawled out across the floor. Above them, lining the museum’s iconic spiral interior, others held red banners which proclaimed, in large black letters, “400,000 DEAD,” “SHAME ON SACKLER,” and “TAKE DOWN THEIR NAME.” Mock prescriptions for OxyContin fluttered down from the ceiling, landing at the feet of Nan Goldin—the photographer and activist who founded P.A.I.N., the group that had organized the protest via Instagram. To the uninformed, the scene may have looked like an elaborate piece of performance art—not unexpected for a museum famous for its elaborate and provocative installations. In this case, it was something altogether different: an outside group, invading the museum to wage an ideological battle.

Welcome to a new form of protest: the museums are the battlefield, and the war—though not exclusively—is about who gets to empower art.

Goldin is a recovering OxyContin addict. She has spoken and written openly about her struggles, and founded P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) in order to protest the Sackler family. The Sacklers own Purdue Pharma, the company that produces and markets OxyContin. P.A.I.N.’s mission statement, in no uncertain terms, decries the Sackler family’s wealth as “blood money” and calls for “all… institutions worldwide [to] remove Sackler signage and publicly refuse future funding from the Sacklers.” P.A.I.N., at least on the surface, seems no different than other movements which call for organizations or individuals to refuse “dirty money.”

But this story is different. Nan Goldin is as much an artist as she is an activist. In fact, some of her works hang in the Guggenheim’s galleries. And she’s taken her war against the Sackler family not to the Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at NYU Langone Health, nor to the Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology at Columbia, nor to the many other Sackler-named institutions scattered across the United States, but rather to the Guggenheim, which houses the Sackler Center for Arts Education, and to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose famous Temple of Dendur is housed in the Sackler Wing. The Sackler family name is on the door of countless institutions, yet Goldin, and P.A.I.N., have chosen museums as the sites of their protests. For Goldin, the Sacklers’ involvement in museums is the worst offense of all—the association of their “dirty money” with the art world is somehow more despicable than an association with any other industry.

Goldin and P.A.I.N are not alone. On March 22nd, 2019, the activist group Decolonize This Place kicked off their “Nine Weeks of Art and Action” at the Whitney, an art museum less than two miles from the Guggenheim. Like P.A.I.N., Decolonize This Place primarily protests museums and their donors, and is calling for the removal of Warren Kanders. Kanders serves as the Vice Chairman of the Whitney and also owns Safariland, a manufacturer of military and law enforcement equipment, including the tear gas being used at the U.S.-Mexico border. In the nine weeks leading up to the Whitney’s biennial celebration, Decolonize This Place has chosen to protest every Friday night, blocking the art of the Whitney with colorful banners of their own. This protest, too, seems at home within the museum’s aesthetic; the banners of the protestors evoke images from the Whitney’s exhibition aptly titled “An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections From the Whitney’s Collection, 2014-2017,” which ran from August 2017 until August 2018. Decolonize This Place have not taken their protests to the Winston Churchill Foundation, where Kanders is also a board member, nor have they gone to the NYPD, who also use Safariland-made gear (although some signs at their protests are dedicated to this issue as well). Instead, Decolonize This Place, like Goldin and P.A.I.N., have made the museum their battleground, decrying the influence that Kanders and, in P.A.I.N.’s case, the Sackler family, have on the museum specifically. Why?

Protests like these call upon a long tradition of criticism, one which challenges the notion that museums are zones of neutrality. This tradition is most coherently reflected throughout the canon of the philosophy of art, in which , one after another, philosophers dispute what, exactly, qualifies as art. Arthur Danto, former Columbia professor and a philosopher of art, explains in his essay, “The Artworld,” that over time, different theories of art have dictated what art is—and, in turn, dictated which works make it into museums.

A museum, by its very nature, declares “this is art.” The works that hang in its galleries, line its halls, and fill its sculpture gardens, are all “art;” the pieces left on the outside, excluded from the hallowed halls of the museum, as Danto points out, are consequently not art. This has powerful ramifications: with the ability to decide what is and is not art comes, as Danto argues, the ability to decide whose voice matters, and whose does not. In his essay “The Artworld Revisited,” Danto argues for a new theory of art which would be practically all-encompassing, in an attempt to create space for as many voices within the artworld as possible. We have yet to see the realization of such a theory—no museum, so far, has seemingly been able to accept such a vast and expansive definition of art. Instead, museums still operate with narrow definitions and act as the all-powerful judges of what counts as art and what does not, a fact with stunning implications.

Organizations such as Goldin’s P.A.I.N. and Decolonize This Place are far from the first to recognize the impact of museums, or to use them as a battleground to combat broad issues. In 1985, a group of women formed the Guerrilla Girls, an activist group dedicated to fighting gender inequality in the art world. The impetus of their formation? An exhibit at the MoMA, titled “An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture,” which claimed to showcase the most significant contemporary artworks to-date. The exhibit featured 148 male artists and only 13 females, with 0 artists of color represented. Though the Guerrilla Girls have gone on to protest inequality in a variety of spheres, one of their primary goals continues to be fighting for equal representation in museum galleries. To be included in a gallery, they protest, is more than simply seeing your paintings on the wall; instead, it is a powerful statement about whether your work is—or is not—art, and therefore whether or not your voice and vision matter in contemporary culture.

The reasons that Goldin, P.A.I.N., Decolonize This Place and the Guerrilla Girls have chosen to protest at museums all center around the power of the museum, and the questions of who gets to be included in the cultural conversation. These arguments should sound familiar to Columbia students, who are well-versed in conversations about the power of being included in the canon. Few professors of the Core curriculum will finish a semester or two of class without at least some time dedicated to a discussion on the power and problems of the canon. Over the years, the syllabi of all Core classes have evolved to include more minority artists, writers, and thinkers. The canon, for all intents and purposes, is a museum: if you’re in, you and your work matter; if you’re not, you and your work do not.

This power—the ability to decide what works should or shouldn’t endure—is one that many of these institutions often abuse. But it’s also one that they use, in incredibly powerful ways. On February 3rd, 2017, less than ten days after President Trump issued a travel ban on Iran, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, Syria, North Korea, and Venezuela, the MoMA pulled works by Picasso and Matisse (among other Western artists) off the walls of one of their galleries, replacing them instead with work from artists born in the countries blocked by the travel ban. This wasn’t a subtle act of protest; next to each of the replaced artworks was hung a plaque that clearly explained that the artists of these works were from the banned countries, and that their work had been re-hung by the MoMA “to affirm the ideals of welcome and freedom as vital to this Museum as they are to the United States.”

The MoMA isn’t the only museum to have created exhibits which serve as purposeful acts of protest. Two weeks later, on February 16th, 2017, the Davis Museum in Wellesley, MA protested the travel ban by removing all works of art created by artists from the banned nations, showcasing, through the blank spaces in various galleries, these artists’ importance. And museums don’t just protest President Trump or the travel ban. The Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art pushed boundaries with its “Heavenly Bodies” theme earlier this year, which forced viewers to scrutinize Catholic vestments at a time when the Catholic Church itself is under similar scrutiny.

Of course Nan Goldin took her fight with the Sackler Family to the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Of course Decolonize This Place went to the Whitney over the Winston Churchill Foundation. Because museums monopolize, for better and for worse, the art world, directly impacting the way we see art and artists, deciding which works we’ll remember and which we’ll forget, which we’ll have access to and which will gather dust in a basement somewhere, and ultimately whose voices we’ll listen to and whose will be silenced forever.

There is an interesting post-script to this story, which is still being written. In March, around a month after Nan Goldin’s protest at the Guggenheim, the Tate Museum in London and the Guggenheim Museum each announced separately that they would no longer be accepting donations from the Sackler family. The Sackler Trust, the charity arm of the Sackler family, issued a statement saying that they would be halting donations in the United Kingdom. As new allegations swirl, and the number of states in the U.S. suing Purdue Pharma continues to climb (the current count is around three dozen), the work that Goldin has done is suddenly highlighted, even more, as the ultimate success story. At the protest at the Whitney by Decolonize This Place, which kicked off their nine weeks of protests, a member of P.A.I.N. took the microphone and, smiling, assured protesters that “direct actions work.” The theme of that night, according to ArtNews, was one sentence, repeated by many of the activists present: “This is only the beginning.”

//YAIRA KOBRIN is sophomore in Columbia College and Deputy Literary & Arts Editor of The Current. She can be reached at yk2761@columbia.edu.

Photo courtesy of https://archinect.com/news/article/150121286/anti-opioid-activists-protest-guggenheim-s-ties-to-sackler-family-the-prominent-art-donors-making-billions-from-oxycontin.

Photo courtesy of https://archinect.com/news/article/150121286/anti-opioid-activists-protest-guggenheim-s-ties-to-sackler-family-the-prominent-art-donors-making-billions-from-oxycontin.